In this chapter your will learn about or refresh your knowledge on the first European poetess Sappho. Then you will read a text about Sappho written by French medieval writer Christine de Pizan. In addition, you will learn more about her inspiring text City of Ladies and reflect upon her vision of female role models.

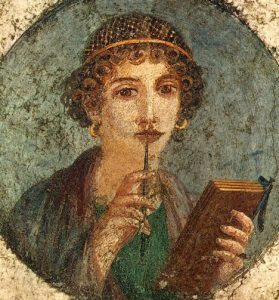

Sappho of Lesbos (c. 620-570 BCE) was a lyric poet whose work was so popular in ancient Greece and beyond that she was honored in statuary and praised by figures such as Solon and Plato. Very little is known about her life and of the nine volumes of her work (which were widely read in antiquity) only fragments survive. Contrary to popular opinion on the subject, her works were not destroyed by closed-minded Christians seeking to suppress lesbian love poetry but were lost simply through time and circumstance. Sappho wrote in the Aeolic Greek dialect, which was difficult for Latin writers (who were well versed in Attic and Homeric Greek) to translate. They were aware that once there had existed a highly praised female poet from the works of others, and they preserved those Sappho’s poems which others had copied, but they did not copy others simply because they did not know her dialect . Some kind of written works were composed during her lifetime or shortly after because the outline of her life was known by later writers, aside from the inscriptions such as the Parian Marble (a history of certain events in Greece between 1582-299 BCE), it is not known what these works were. Her name has leant itself to `lesbian’ and `Sapphic’, both relating to homosexual women, because of her extant poetry which concerns itself with romantic love between women.

Mark, Joshua J. “Sappho of Lesbos.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 02 Aug 2014. Web. 13 Mar 2020. CC BY-NC-SA. Read the complete article!

Watch the video about Sappho by Dr. Daniel Orrells.

Read more about Sappho in the text below:

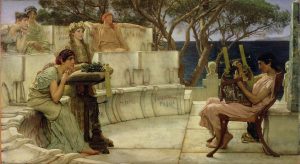

The world of Sappho’s poems is, at least as far as we can tell from the fragments that have survived to this day, a world in which the central place is occupied by a woman both in the role of the lyric subject and of the object she is talking about. Poetic rumour enlivens images from the lives of women that we look at from a different perspective than revealed in the poems of other ancient Greek lyricists.

In her poetry, both lyrical subject and object are female. This duality is perhaps most pronounced in a poem about Arignota, where the poet expresses the pain of a woman who had to leave her friends on Lesbos for marriage. The poet, along with the girl Atthis, remembers the days when Arignota enjoyed the sounds of songs sung by Atthis. Sappho not only celebrates Arignota, but also Atthis, creating a sense of connection and friendship between women; we find this sentiment more than once in the literature written by a female pen.

Now she shines among Lydian women as

into dark when the sun has set

the moon, pale-handed, at last appears

making dim all the rest of the stars, and light

spreads afar on the deep, salt sea,

spreading likewise across the flowering cornfields;

(Sappho 96, Lattimore #7)Translation from Richmond Lattimore: Greek Lyrics, Chicago, 1960).

The poet makes the woman’s sadness convincing by the following turn: Arignota changes from the object of description into the subject who expresses her emotions.

Sappho expresses the pain of an ancient woman who had to leave her home and the community to marry. This feeling is perhaps even more directly expressed in the song “Honestly, I would like to die”, where the poet relives the farewell of one of her girls, who is most likely leaving her for marriage.

In both poems, one can also admire the poet’s rich metaphorical world in which a woman is never compared to an animal but is surrounded by a world of magical fragrances and flowers that have symbolic meaning. Violets adorn Aphrodite and muse, lotus is the flower of immortality, grass flowers belong to the cult of Persephone, as Hades abducted her when she tore them. Sappho’s descriptions of the flowers and beauty of the girls surrounding her are the embodiment of the greatest virtue reflected in poetry, in a world very different from the world of warriors and famous battles sung by ancient poets. The fierceness and lack of sense of beauty is revealed to the poet as an insult to her emotions.

Nature and the maidens are one, the harmony reigns between them and green groves and soft meadows. A woman is not subjected to nature in the way that it would overwhelm her and so that she could not control her mind. She is not represented as an irrational being, which is completely different from the representations of women by her male contemporaries. Ever since antiquity, the images of femininity in the works of art do not correspond with the actual lives of women, since in literary works they move between the poles of idealized, glorified femininity and its opposite – of the demonic woman who brings perdition. Sappho also compares girls to nature, but her verses do not reveal the fatal submission of a woman to nature, as they are merely a vicious illustration, such as a description of a girl who has not yet found a husband:

Christine de Pizan (also given as Christine de Pisan, l. 1364 – c. 1430 CE) was the first female professional writer of the Middle Ages and the first woman of letters in France. She was born in Venice, Italy but her family soon moved to France when her father was appointed astrologer to the court of the French king Charles V (r. 1364-1380 CE). Although she always valued her Italian heritage, she was devoted to France and the royal court throughout the rest of her life.

She was widowed when her husband died of the plague in 1389 CE, leaving her with three children and the responsibility of caring for her mother and niece. With no other options open to her to earn a living, Christine took to writing. She penned romantic ballads for the French aristocracy which were so well-received she pursued writing as a career. Among her best-known works are:

Although modern-day scholars continue to debate whether she can be called a “feminist”, as the concept did not exist in her lifetime, there is no denying that she embodied the values and principles of feminism, specifically the idea that women were the equal of men in every regard and should be given the same rights, opportunities, and respect. Her works would influence later writers, male and female, in particular through the early era of the Renaissance; after that they fell out of favour and were only rediscovered in the late 19th century CE. (Mark 2019)

Read the complete article about Christine de Pizan!

What does Christine de Pizan set above female beauty? Does this idea break with the traditional view of a woman? Justify your answer.

Why does she refer to Boccaccio when listing Sappho’s virtues?

Boccaccio and Pizan use metaphors to describe Sappho’s talents:

“She entered the forest of laurel trees filled with may boughs, greenery, and different colored flowers, soft fragrances and various aromatic spices, where Grammar, Logic, noble Rhetoric, Geometry, and Arithmetic live and take their leisure. She went on her way until she came to deep grotto of Apollo, god of learning, and found the brook and conduit of the fountain of Castalia, and took up the plectrum and quill of the harp and played sweet melodies, with the nymphs all the while leading the dance, that is, following the rules of harmony and musical accord.” (Christine de Pizan: The Book of the City of Ladies, Persea Books, New York, p. 67.

Transform the text into “plain” language.

Now read two paragraphs about The Book of the City of Ladies (1405 CE) from the review of the English translation of the aforementioned Pizan’s work, written by Joan M. Ferrante and published in Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Autumn, 1983), pp. 244-247:

In the City of Ladies, Christine de Pizan takes a positive approach, constructing an allegorical city under the guidance of Raison (Reason), Droiture (which Richards translates as Rectitude), and Justice. The walls of the city are built by legendary women (some are mythic, but all, even the goddesses, are treated as historical beings). Some of them have founded or governed lands; others of them are learned and clever women who invented or practiced various branches of art and science and craft. The inner part of the city is the contribution of prophets and of devoted daughters, wives, and mothers, whose virtues and strengths were exercised to the benefit not only of their families but often of their peoples. The roofs of the city are made by the queen of heaven (who calls herself the “chief du sexe feminin”), and by saints and martyrs. Although Christine de Pizan draws heavily on Boccaccio for many of her stories, she reorganizes the material to give emphasis to women’s contributions to civilization; she presents them, particularly in the first book, as the source of laws and justice, and as founders of cities, inventors of alphabets and grammar, numbers, weaving, dying. She offers these stories to counter men’s claims that women are useful only to bear children and sew, and berates men, through the words of Reason, for their “massive ingratitude. . . like people who live off the goods of others without knowing their source,” and noting that God, “who does nothing without a reason,” showed that he does not despise the sex, since he made their brains capable not only of learning and retaining the sciences, but of discovering new ones (1.37.).

Christine de Pizan makes a strong case for women’s intellect. Although she does not think it appropriate for women to engage in the various branches of the legal profession because of their physical weakness and vulnerability, she does assert their mental capacity to do so, arguing that they “have been very great philosophers and have mastered fields far more complicated, subtle, and lofty than written laws and man-made institutions” (1.11.). She claims, always with the voice of Reason instead of her own, that “if it were customary to send daughters to school like sons, and if they were then taught the natural sciences, they would learn as thoroughly and understand the subtleties of all the arts and sciences as well as sons.” Then she makes an added point which turns physical disadvantage to a strength: “just as women have more delicate bodies than men, weaker and less able to perform many tasks, so do they have minds that are freer and sharper whenever they apply themselves” (1.27.). She disproves the argument that education is morally harmful to women by many examples of learned and virtuous women, several of whom were trained by their fathers to carry on in the family profession. She remarks that foolish men claim education is harmful because they do not like women to know more than they do (II.36.4). She also makes telling points when she notes that Christ praised the words of the Canaanite woman and did not disdain to discuss her salvation with the Samaritan woman at the well, who spoke “with great eloquence… on her own behalf.” She asks, “How often would our contemporary pontiffs deign to discuss anything with some simple little woman [une simple femmelette], let alone her own salvation?” (1.10.5).

Sappho was the source of inspiration also for other women. In the Victorian era, Caroline Norton wrote about her.

Caroline Norton, original name in full Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Sheridan, (born March 22, 1808, London, England—died June 15, 1877, London), English poet and novelist whose matrimonial difficulties prompted successful efforts to secure legal protection for married women. She published powerful volumes of verse on social problems: A Voice from the Factories (1836) and The Child of the Islands (1845). She also wrote several novels, two of which, Stuart of Dunleath (1851) and Lost and Saved (1863), are based on her own experience of domestic misery. She is said to have been the model for the heroine of George Meredith’s novel Diana of the Crossways (1885). After her husband’s death in 1875, she married Sir William Stirling-Maxwell.

Caroline Norton, original name in full Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Sheridan, (born March 22, 1808, London, England—died June 15, 1877, London), English poet and novelist whose matrimonial difficulties prompted successful efforts to secure legal protection for married women. She published powerful volumes of verse on social problems: A Voice from the Factories (1836) and The Child of the Islands (1845). She also wrote several novels, two of which, Stuart of Dunleath (1851) and Lost and Saved (1863), are based on her own experience of domestic misery. She is said to have been the model for the heroine of George Meredith’s novel Diana of the Crossways (1885). After her husband’s death in 1875, she married Sir William Stirling-Maxwell.

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica.

I.

THOU! whose impassion’d face

The Painter loves to trace,

Theme of the Sculptor’s art and Poet’s story–

How many a wand’ring thought

Thy loveliness hath brought,

Warming the heart with its imagined glory!

II.

Yet, was it History’s truth,

That tale of wasted youth,

Of endless grief, and Love forsaken pining?

What wert thou, thou whose woe

The old traditions show

With Fame’s cold light around thee vainly shining?

III.

Didst thou indeed sit there

In languid lone despair–

Thy harp neglected by thee idly lying–

Thy soft and earnest gaze

Watching the lingering rays

In the far west, where summer-day was dying–

IV.

While with low rustling wings,

Among the quivering strings

The murmuring breeze faint melody was making,

As though it wooed thy hand

To strike with new command,

Or mourn’d with thee because thy heart was breaking?

V.

Didst thou, as day by day

Roll’d heavily away,

And left thee anxious, nerveless, and dejected,

Wandering thro’ bowers beloved–

Roving where he had roved–

Yearn for his presence, as for one expected?

VI.

Didst thou, with fond wild eyes

Fix’d on the starry skies,

Wait feverishly for each new day to waken–

Trusting some glorious morn

Might witness his return,

Unwilling to believe thyself forsaken?

VII.

And when conviction came,

Chilling that heart of flame,

Didst thou, O saddest of earth’s grieving daughters !

From the Leucadian steep

Dash, with a desperate leap,

And hide thyself within the whelming waters?

VIII.

Yea, in their hollow breast

Thy heart at length found rest!

The ever-moving waves above thee closing–

The winds, whose ruffling sigh

Swept the blue waters by,

Disturb’d thee not!–thou wert in peace reposing!

IX.

Such is the tale they tell!

Vain was thy beauty’s spell–

Vain all the praise thy song could still inspire–

Though many a happy band

Rung with less skilful hand

The borrowed love-notes of thy echoing lyre.

X.

FAME, to thy breaking heart

No comfort could impart,

In vain thy brow the laurel wreath was wearing;

One grief and one alone

Could bow thy bright head down–

Thou wert a WOMAN, and wert left despairing!

This activity requires a good knowledge of English as well as good interpretation skills when it comes to interpreting literature.

During your first reading, pay attention to punctuation. What is the (verbal/grammatical) mood of each stanza? Which person narration is chosen by Caroline Norton when she speaks about Sappho? How does C. Norton present Sappho?

In the second stanza, by using an exclamation mark, she raises doubts about whether the actual Sappho matches the one we know from the literature and arts in general. Turn the archaic forms into contemporary speech.

In stanzas III and VII, the poet raises a lot of questions for Sappho, namely, questions that pertain to the legend about her death. If you are not familiar with it, use this site to gain knowledge about it.

How does Norton describe Sappho’s death? Explain in your own words.

Why does C. Norton say “Vain was thy beauty’s spell– // Vain all the praise thy song could still inspire–“? Do you see these lines as a display of a pessimistic outlook on women’s literary creativity?

Three words in the poem are written in capital letters, why do you think that the poet decided to expose those words?

Go to the Virtual Research Environment NEWW Women Writers. Look for Christine de Pisan in the category Authors (write just her surname). Then click in the left column on “Reception of this author”. Explore her receptions and write a short report about your findings.

Write an essay about an imagined place of your own. Which women from the history or from your own environment would you invite in this place of retreat and why?

Christine de Pisan is one of the “World-Changing Women”. Learn more about them on the interactive map designed by The Open University.

For centuries, Sappho has been perceived as the first female poet. However, in 1927 Sir Leonard Wooley discovered a calcite disc with the figure of Enheduanna. In 1958, Adam Falkenstein published “Enhedu’anna, The Daughter of Sargon of Akkad”, the first scholarly article on Enheduanna, ten year later the first translations of Enheduanna’s hymns were published. (See also Wikipedia article about Enheduanna.)

Enheduanna, the poet of religious hymns, lived and created approximately half a century before the creation of the most important work of the Sumero-Akkadian literature, namely, the Epic of Gilgamesh. Endehuana is the first person whose literary authorship is noted in world literature. Considering the position women had in the Mesopotamian society, this is not as surprising as it may seem. Because of social stratification in Mesopotamia, all women didn’t have access to literacy, however, the representatives of the elites, wives and daughters of leaders, knew how to read and write and they even conducted business ventures. They took part in sales business, they acquired land, still, it is hard to say how free they actually were. The role of women was mostly limited to them being the bearers of male descendants whose main task was to take care of elderly people.

Women were quite active as musicians, scribes, administrative workers and priestesses. They could live in a palace or a temple, or, if they had a family, also elsewhere, and they were able to perform many activities. They were paid for their work, mostly in the form of food, clothing or other objects. It was much harder for women who had to do physical labour and got half of men’s salary for it. Some were prostitutes. Supernatural powers were mostly ascribed to women, not men.

Enheduana was the only daughter of the king Sargon of Akkad, who ruled around 2300 BC and is known as the founder of the Akkadian Empire. Her father named her a priestess in 2270 BC, and married her symbolically to Nanna, the Sumerian God of the Moon. His daughter Inanna was the goddess of fertility, love but also discord. Enheduana dedicated her praying rituals to Nanna and in her hymns, she addressed Inanna and she places Inanna in a higher hierarchical place than Anu, the supreme Sumerian deity. In her literary works, she uses Sumerian, her mother tongue. Three hymns are preserved in cuneiform, on tablets which were created approximately five centuries after Enheduana. As two of the hymns mention her name (in the first person) and the third hymns is much like other two, the third hymn is also believed to be hers. The first hymn describes the battle between Inanna and the Ebih mountain; Inanna asks Anu for help, but he rejects her, as he is afraid of the mountain. Inanna doesn’t give up and eventually beats the mountain.

In the second hymn, she praises Inanna’s amazing powers shown in various forms, the third hymn uses these powers in a metaphorical sense: Inanna as a dragon, the south wind, a bull, a cow and a storm, and a harp of lament. Her powers are exceptional and she shows that to the people when they pray to her: their rivers bleed, a wife doesn’t say sweet things to her husband anymore at midnight she doesn’t reveal her secrets and the silent longings of her heart anymore. In the second part of that hymn, the poet talks about her sad faith, after the mean Lugalane banished her nephew from the throne; she says: “I, high priestess, I, Enheduana.”

Her lines have multiple meanings, they are sensual, intimate and very personal. At the end of the hyms, Enheduana is listed as the “collector” of texts, hence it is difficult to say how many of the texts are indeed hers and in how many she merely inspired herself with the works of other male and female authors; we will probably never get the final answer. Literary studies mostly list her as the author, but also state that later additions, as with all the works that reached us through copying of other texts, are not impossible.

Further Watching

Watch Cass Dalglish’s inspiration of Enheduanna’s poetry. Learn more about Cass Dalglish.

References

Mark, Joshua J: “Christine de Pizan.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 26 Mar 2019. Accessed 13 March 2020.