5

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will learn about or refresh your knowledge on Jane Austen. You will read an excerpt from the novel Northanger Abbey where she mentions Maria Edgeworth and discusses the importance of her novels. You will also learn about the courtship novel and explore how this definition matches Austen’s novels. Finally, you will get acquainted with The Reading Experience Database and will be able to explain the differences between Austen’s and Brontë’s perception of the domestic world as it is mirrored in their writing style.

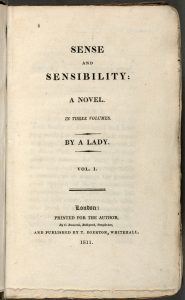

Jane Austen, (born December 16, 1775, Steventon, Hampshire, England—died July 18, 1817, Winchester, Hampshire), English writer who first gave the novel its distinctly modern character through her treatment of ordinary people in everyday life. She published four novels during her lifetime: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1815). In these and in Persuasion and Northanger Abbey (published together posthumously in 1817), she vividly depicted English middle-class life during the early 19th century. Her novels not only defined the era’s novel of manners, but they also became timeless classics that remained critical and popular successes two centuries after her death.

Brian C. Southam: Jane Austen, Enciclopaedia Britannica.

Watch the documentary about Jane Austen.

Activity 1

- Describe the importance of the library owned by Austen’s father.

- What was the status of the novel in Austen’s times.

- Who were the male and female authors whose influence on Austen was of great importance?

- How is the conflict between classicism and romanticism mirrored in the novel Sense and Sensibility?

- Which descriptions of characters in Pride and Prejudice are praised for being realistic?

- In which novel do we meet a heroine as a young girl and follow her story from childhood onwards?

- What have you learned about the publishing world?

- How does Mr. Knightley’s proposal to Emma reflect Austen’s matured style?

- In what ways does the heroine of Persuasion differ from other Austen’s heroines?

Northanger Abbey

Read a summary of the novel and take the plot overview quiz. You can also watch the movie.

Jane Austen: The Northanger Abbey (1817)

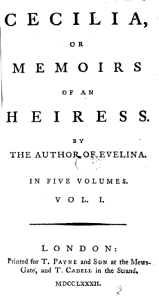

The progress of the friendship between Catherine and Isabella was quick as its beginning had been warm, and they passed so rapidly through every gradation of increasing tenderness that there was shortly no fresh proof of it to be given to their friends or themselves. They called each other by their Christian name, were always arm in arm when they walked, pinned up each other’s train for the dance, and were not to be divided in the set; and if a rainy morning deprived them of other enjoyments, they were still resolute in meeting in defiance of wet and dirt, and shut themselves up, to read novels together. Yes, novels; for I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel-writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding—joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? I cannot approve of it. Let us leave it to the reviewers to abuse such effusions of fancy at their leisure, and over every new novel to talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans. Let us not desert one another; we are an injured body. Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world, no species of composition has been so much decried. From pride, ignorance, or fashion, our foes are almost as many as our readers. And while the abilities of the nine-hundredth abridger of the History of England, or of the man who collects and publishes in a volume some dozen lines of Milton, Pope, and Prior, with a paper from the Spectator, and a chapter from Sterne, are eulogized by a thousand pens—there seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labour of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them. “I am no novel-reader—I seldom look into novels—Do not imagine that I often read novels—It is really very well for a novel.” Such is the common cant. “And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame.  “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. Now, had the same young lady been engaged with a volume of the Spectator, instead of such a work, how proudly would she have produced the book, and told its name; though the chances must be against her being occupied by any part of that voluminous publication, of which either the matter or manner would not disgust a young person of taste: the substance of its papers so often consisting in the statement of improbable circumstances, unnatural characters, and topics of conversation which no longer concern anyone living; and their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favourable idea of the age that could endure it.

“It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. Now, had the same young lady been engaged with a volume of the Spectator, instead of such a work, how proudly would she have produced the book, and told its name; though the chances must be against her being occupied by any part of that voluminous publication, of which either the matter or manner would not disgust a young person of taste: the substance of its papers so often consisting in the statement of improbable circumstances, unnatural characters, and topics of conversation which no longer concern anyone living; and their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favourable idea of the age that could endure it.

Source: Jane Austen: The Northanger Abbey

Jane Austen names the heroines of Maria Edgeworth’s novels. Ellen Moers wrote about Austen’s relationship towards her predecessors: “The fact is that Austen studied Maria Edgeworth more attentively than Scott, and Fanny Burney more than Richardson; and she came closer to meeting Mme de Staël than she did to meeting any of the literary men of her age.” (Moers 21985: 44-45)

If you are not familiar with Maria Edgeworth, read about her below.

Maria Edgeworth was born on January 1, 1767, Blackbourton, Oxfordshire, England and died on May 22, 1849 in Edgeworthstown, Ireland. She wrote children’s books and novels.

“She lived in England until 1782, when the family went to Edgeworthstown, County Longford, in midwestern Ireland, where Maria, then 15 and also the eldest daughter, assisted her father in managing his estate. By doing this, she acquired the knowledge of rural economy and of the Irish peasantry that was to be the backbone of her novels. Domestic life at Edgeworthstown was busy and happy. Encouraged by her father, Maria began her writing in the common sitting room, where the 21 other children in the family provided material and audience for her stories. She published the stories entitled The Parent’s Assistant in 1796. Even the intrusive moralizing, attributed to her father’s editing, does not wholly suppress their vitality, and the children who appear in them, especially the impetuous Rosamond, are the first real children in English literature since Shakespeare. Her first novel, Castle Rackrent (1800), written without her father’s interference, reveals her gift for social observation, character sketch, and authentic dialogue and is free of lengthy lecturing. It established the genre of the “regional novel,” and its influence was enormous; Sir Walter Scott acknowledged his debt to Edgeworth in writing Waverley. Her next work, Belinda (1801), a society novel, unfortunately marred by her father’s insistence on a happy ending, was particularly admired by Jane Austen.”

“She lived in England until 1782, when the family went to Edgeworthstown, County Longford, in midwestern Ireland, where Maria, then 15 and also the eldest daughter, assisted her father in managing his estate. By doing this, she acquired the knowledge of rural economy and of the Irish peasantry that was to be the backbone of her novels. Domestic life at Edgeworthstown was busy and happy. Encouraged by her father, Maria began her writing in the common sitting room, where the 21 other children in the family provided material and audience for her stories. She published the stories entitled The Parent’s Assistant in 1796. Even the intrusive moralizing, attributed to her father’s editing, does not wholly suppress their vitality, and the children who appear in them, especially the impetuous Rosamond, are the first real children in English literature since Shakespeare. Her first novel, Castle Rackrent (1800), written without her father’s interference, reveals her gift for social observation, character sketch, and authentic dialogue and is free of lengthy lecturing. It established the genre of the “regional novel,” and its influence was enormous; Sir Walter Scott acknowledged his debt to Edgeworth in writing Waverley. Her next work, Belinda (1801), a society novel, unfortunately marred by her father’s insistence on a happy ending, was particularly admired by Jane Austen.”

Source: Enciclopeadia Brittanica.

She is convinced that her child died because she succumbed to the then fashion among noblewomen to breastfeed, even though it was believed that that didn’t enable the best possible development for the child. In her narrative, Lady Delacour also reveals all the sadness associated with arranged marriages among aristocrats; her marriage doesn’t make her happy, so she searches for distractions in flirting with other men, in shallow social interactions and in striving to achieve the leading position among high society women in London. Belinda is appalled by Lady Delacour’s ruined marriage and also by the fact that their daughter Helen is raised in a middle class family. With Belinda’s help, Lady Delacour manages to discard some of her bad habits. The highlight of their friendship is represented by Lady Delacour’s confession about a wound on her breasts which she got when she, dressed up as a man, was in duel with another woman, also dressed up as a man. She is convinced that this wound gave her cancer and that she would soon die. Influenced by a scheming servant, she accuses Belinda of seducing Lord Delacour, so Belinda is sent away. Belinda moves to the Percivals, a family, who is an embodiment and an idealization of the domestic values. Lady Anne Percival is gentle, maternal and sensitive, mostly satisfied with her role of a wife and a mother. She is educated, well read and represents Belinda’s role model. Clarence Hervey is in love with Belinda, but he soon finds himself in a moral dilemma. He was supposed to marry Virginia, who was already being prepared for this marriage by him, but he doesn’t love her. Virginia sets him free with her confession that she is in love with someone else and that Hervey can marry Belinda. At the end of the novel, the title character not only gets a husband, but also contributes to Lady Delacour’s transformation. Namely, Lady Delacour becomes the main supportive figure in their home and by that, she enables her family to be happily reunited once again.Before that, she also makes sure that Belinda doesn’t marry her Creole suitor and slave owner (critics identify in this element a colonial nature of the novel). Apart from the seeming simplicity of the story line, the novel nevertheless continuously moves along the lines of womanhood/manhood, inner self/ outer self, English/ foreign, home/ public sphere, white/ black. Marriage is shown as a market place, where the qualities of a girl should be advertised in the same way one would advertise goods. Belinda is, throughout the narrative, an exemplary character, but others have many flaws. In relation to Virginia, Clarence is patronizing and hides her from the world without any hesitation – all this with the purpose of raising an obedient wife.The author is openly critical towards the Rousseau’s concept of raising the ideal woman. It is very likely that the most interesting character in the novel is Harriot Freke, a woman who challenges Lady Delacour to a duel, a bold woman who doesn’t care much about her femininity and the etiquettes related to it; she wears men’s clothes, demands rights for women and passionately schemes against Lady Delacour when she is disappointed in Lady Delacour’s behaviour. Before that, they were great friends. The narrator strictly refuses and criticizes her actions, however, her presence in the novel points to the observation that womanliness is not a uniform category. Also, the black African servant is shown in a positive light by M. Edgeworth. He marries an English peasant girl and becomes a tenant of an estate, however, this particular part was left out the third edition of the novel. The novel ends with Lady Delacour’s arrangement of a “tableau vivant” (living pictures).

Belinda is a courtship novel. Read Katherine Sobba Green’s definition of a courtship novel:

“What distinguished courtship novels from other contemporary narratives was that thematically they offered a revisionist view: women, no longer merely unwilling victims, became heroines with significant, though modest, prerogatives of choice and action. Naturally, over its eighty year history the courtship novel varied its formal expression with literary fashion and its politics according to the class and circumstances of its author, so that it is neither desirable nor possible to specify a normative plot outline. More often then not, however, the courtship novel began with the heroine’s coming out and ended with her wedding. It detailed a young woman’s entrance into society, the problems arising from that situation, her courtship, and finally her choice (almost always fortunate) among the suitors. Thematically, it probed, from a woman’s point of view, the emotional difficulties of moving toward affective individuation and companionate marriage despite the regressive effects of female role definition. In this sense, the novel of courtship, appropriated domestic fiction to feminist purposes. By creating a feminized space-that is by centering its story in the brief period between a young woman’s coming out and her marriage-this subgenre fostered heightened awareness of sexual politics within the gendered arena of language, especially with regard to defining male and female spheres of action.” (Green 1991: 2-3).

Activity 2

Where does the plot of Belinda overlap with the definition of the courtship novel?

How does Edgeworth challenge the “male and female spheres of action”?

Think about the contrast between Mrs. Anne Percival and Lady Delacour. Can you discover any traits of feminist stance in the novel Belinda?

Read a Jane Austen novel. Do you think that her novels could be described as courtship novels? Explain your answer and back it up with examples from the respective novel.

Now look for the receptions of Austen’s novel among her readers. Go to the of The Reading Experience Database, created by the Open University, UK. Then go to the “Search” page and scroll down to ‘Advanced search’. In the box ‘Keyword (in evidence)’ type ‘Austen.’ Then in the section headed ‘Reader/Listener/Reading Group’, type ‘Charlotte Brontë’ in the ‘name’ box. Where it says ‘search for name in’, choose ‘reader.’ Scroll right down the page and hit ‘submit’. You should find Brontë’s opinion about Austen:

“I have likewise read one of Miss Austen’s works “Emma” – read it with interest and with just the degree of admiration which Miss Austen herself would have thought sensible and suitable – anything like warmth or enthusiasm; anything energetic, poignant, heartfelt, is utterly out of place in commending these works: all demonstration the authoress would have met with a well-bred sneer, would have calmly scorned as outre and extravagant… she ruffles her reader by nothing vehement, disturbs him by nothing profound: the Passions are perfectly unknown to her; she rejects even a speaking acquaintance with that stormy Sisterhood…'”

What do you think are the reasons for Brontë’s reserved attitude toward Austen? If the question is too difficult, then try to find out about Charlotte Brontë’s style of writing and compare it with Austen’s.

Further Watching

Watch another documentary about Austen.

References:

Green, Katherine Sobba: The Courtship Novel, 1740-1820: A Feminized Genre. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1991.

Moers, Elen: Literary Women. Harden City, New York: Doubleday, 21985.