8

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn about Nordic author Laura Marholm and her book Modern Women. You will discuss the problem of the twofold reception – in author’s lifetime and afterwards – and tackle the question of why so many literary foremothers have been forgotten for a long time.

Laura Marholm and her writings

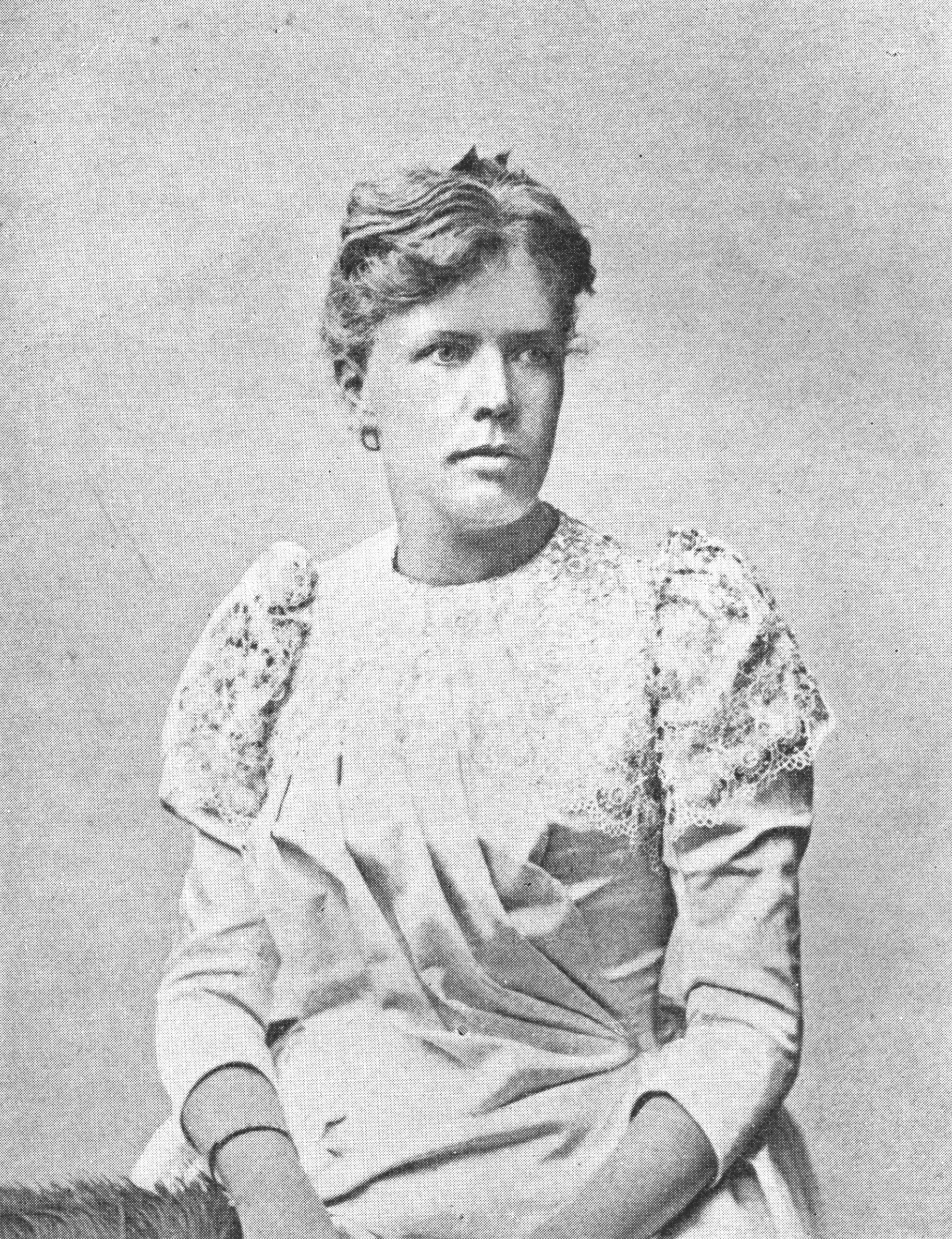

Laura Marholm was born in Riga in 1854. Even though her father, sea captain Frederik Mohr was of Danish-Norwegian descent and Latvia at the time was part of the Russian empire, Marholm’s linguistic and literary socialization was done in German. She grew up in the Latvian capital, was trained to become a teacher and she worked for a local newspaper. In 1880, she published her first play, a tragedy called Johann Reinhold Patkul, and later on another play titled Frau Marianne (Mrs. Marianne, 1882).

The staging of the two plays in Riga was successful. With the help of Georg Brandes’ essays which Marholm read, she became very much interested in Ibsen and Scandinavian authors and moved to Copenhagen in 1895. She worked as a translator to support herself. In 1889, she married Swedish writer Ola Hansson (1860–1925), soon she gave birth to her son Ola and started taking care of her husband’s work. Because of his influence, writing about erotic experiences as the most important drive in a life of a woman became central for her work. She attracted attention with a series of articles titled A Woman in Scandinavian Literature; they were published in 1890 in the Freie Bühne magazine. In 1981, the family moved to Friedrichshagen near Berlin. Laura Marhold joined a (entirely male) poetry club and invited August Strindberg to join them. She soon became the intellectual leader of the group. She surprised the Berlin modernism movement with her dominant act.

She attracted the attention of wider public with her collection of six essays titled Modern Women. After their split with Strindberg, the couple moved to Bavaria, to Schliersee and supported themselves by writing articles and feuilletons. When already living in a new place, the writer published another book of essays, We Women and Our Authors (Wir Frauen und unsere Dichter, 1895) and once again moved towards literature. This phase of her life is noted for her successful collaboration with publisher Albert Langen. However, this was later on followed by torturous court dealings between the two. She also wrote two psychological novellas Was war es? (What was it?, 1895) and Das Unausgesprochene (Unspoken, 1895) and a play titled Karla Bühring (1895). She understood her books as a supplement to Modern Women (Brantly 1991: 120). The novella Das Unausgesprochene is a psychological portrayal of writer Victoria Benedictsson, whom Marholm also describes in her play Karla Bühring. In the novella, however, she turned her into a musician.

In 1897 her new book of essays The Psychology of Woman (Zur Psychologie der Frau) came out and a year later the couple converted to Catholicism. In 1899 they moved to Munich, but their son Ola stayed in Schliersee due to his schooling. Marholm’s psychological problems were getting worse because of the court case involving Langen (Brantly 1991: 131–132) and other blows she received (Brantly 1991: 100, Sprengel 1994: 712). She was suffering from paranoia and her drinking problem got so bad that in 1905 she needed to be hospitalized in a local hospital in Munich. When her condition somewhat improved, she first went to Austria and then to France (Meudon). She spent the last years of her life in an institution called Majorenhof near Riga. She stayed there till her death in 1928. She started writing again after 1918, but with less success than in her earlier years. She collaborated with important Scandinavian critics and artists of her time: Georg Brandes, George Egerton (Brantly 105), Arne Garborg, Ellen Key, Anne-Charlotte Edgren-Leffler, Edvard Munch and others.

Ellen Key ignited Marholm’s interest in the work of Anne-Charlotte Edgren-Leffler and that is also how Marholm’s friendship with Edgren-Leffler started. In May 1893, Key sent a biography of Sonja Kovalevsky (Sofia Kovalevskaya) (written by Edgren-Leffler) to the couple. In the summer of 1894, also the friendship between Laura Marholm and Ellen Key deepened, as they hosted Key in their Bavarian home (Brantly 1991: 105). Suffering from persecution, Laura Marholm was transferred to an institution for several months in April 1905. Later, she lived in Meudon near Paris and in Riga. She only began to work as a writer to a limited extent. She died on October 6, 1928 in Jūrmala in Latvia.

Modern Women

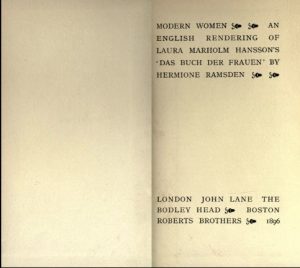

Modern Women came out just before Christmas 1894 (it was dated 1895) and it became the first financial success of Albert Langen, the publisher. Soon after its publication, the book got translated into Swedish, English, Norwegian, Russian, Polish, Czech, Dutch and Italian. For reasons that never got explained, Langen didn’t allow the book to be translated into French, even though the contract included this possibility. On the other hand, the Swedish translation came out without the author’s consent. Marholm and her publisher were good at advertising – they made sure that the review copies made it to the most influential papers. The reception was mixed. Susan Brantly names the phrases that were used to describe the book: “a dangerous book”, “an absurd book”, “an honest and powerful book” and “bad literature” (Brantly 1991: 107). Most of the reviewers were of the opinion that the book was brilliantly written and that the author was a shrewd observer (Ibid.), but they connected this solely with the fact that she emphasized the importance of female independence from men and a fatal mark that a woman gets because of a romantic relationship. It was already Charlotte Broicher, Marholm’s contemporary, who found out that the author gave voice to the oscillations of the soul that were to remain silent until that point, however, she also notes that the majority of women of that time found such revelations of femininity insulting. Broicher posed the question about how such a two-sided view came about (ibid.). Susan Brantly writes that the reason for such non-unified reception lies in the author’s rhetoric; the fact is that it is at the same time appealing and seductive as well as contradictory. Another Marholm contemporary, Adine Gemberg thought that everything in Marholm’s book revolved around one spot; it roars and resounds with grand words, but it doesn’t move anywhere (ibid. 107).

When it was still being debated whether a woman had sex drive or not, the exposure of female sexuality was surely shocking (Brantley 108, Walkowitz 2000: 370). The feminist movement that completely distanced itself from Laura Marholm’s ideas strongly rejected her book Modern Women. At a congress those women held in Berlin in 1896, they called Marholm an enemy of the feminist movement (Brantley 109). One of the most determined German activists fighting for women’s rights, Helene Lange (1848–1930) pointed out that Marholm’s book could be read as a book proposing that motherhood is the only purpose of a woman’s life and thus the book can be abused and misused (ibid. 109).

A German women’s rights activist Hedwig Dohm (1831–1919) was certainly one of the most severe critics of Modern Women. She pointed out that not all women could be treated in the same way and put in the same category. She claimed that not every single woman had a desire to marry or be a mother and that every woman should have a chance to develop her own individuality. Despite such criticism, less than a year after the book’s publication Laura Marholm was proclaimed an expert on women’s issues. She wrote articles for various newspapers and magazines and received many letters from women asking for her advice (Brantly 1991: 119–120). Brantly also notes that the book was provocative because it presented problematic ideas in a convincing manner. In her work Zur Psychologie der Frauen, Marholm suggested – also because of the criticism related to Modern Women – that all women who cannot find happiness in marriage should seek happiness in a convent.

She claimed that a woman cannot create anything anew, cannot make a fresh start, rather, she believed that everything is just a by-product of or a link to something previously created. Even the best women out there cannot transform wrong thoughts into right ones, or a bad seed into a good product (Marholm 1903: 261–262). She also notes that thinking and working women are barren and their children degenerated. Susan Brantly points out that that was a common opinion of the times and advocated by dr. Max Runge and Ellen Key (Brantly 1991: 144). Marholm’s book Zur Psychologie der Frauen also got a lot of attention, mostly in the form of negative criticism.

Modern Women thematized the then topical and lively discussion on new ideas of womanhood. As Brantly states, there was a lot of interest for women at the time; an abnormally strong interest existed in women’s psychology (Lombroso, Freud). It was all centered around an image of a hysterical woman and some critics saw Laura Marholm as a prophet of such hysteria (Brantly 1991: 114). In addition, at the end of the 19th century, Germany was a conservative country that defended women’s calling to become mothers and wives.

The book was liked by those women who felt uncomfortable with all the debates on modern women who were successful in their careers. By reading Modern Women, they got a confirmation that they were doing fine. The truth is that Laura Marholm never denied the importance of a woman’s realization through work and career, she just believed that she could not be entirely fulfilled and happy without finding love and becoming a mother. The contribution of Modern Women to the creation of the “new woman” idea was noticed already by Marholm’s contemporaries, however, they missed its importance for the discourse on female authorship. From today’s perspective, we can’t overlook that which was already pointed out by Susan Brantly: the popularity of Modern Women created a market place for the literary works of women like Amalie Skram in Ellen Key (Brantly 106). And moreover, we need to highlight as a unique quality of Marholm’s book the fact that with the help of this book, the author entered the discussion on whether women write a specific kind of literature. She raised the question of what defines a woman quite a few decades before Simone de Beauvoir.

Marholm juxtaposed the accusations that women faced for centuries – namely, that their works show no originality and breakthrough moments in literary history – with specifics of women’s writing which she described as special qualities. Her contemporaries intentionally and non-intentionally ignored this attempt and quoted (many times in a sensationalist manner) only the most provocative statements from Modern Women. Sometimes those statements were taken out of context as well. Therefore, it seems that a new and detailed reading, analysis and interpretation of Modern Women, the book that has not been discussed much so far, is essential for understanding its innovative value, as well as its entanglement into contradictions and paradoxes that authors who rejected old views and tried to pave their way through a sometimes enormous number of obstacles faced.

The writer supplemented her portrayals of six women with a lengthy introduction in which she stresses that her book is not a study of women’s reason or women’s creative abilities, even though all six women represent a female way of thinking and a woman’s creative sensitivity. Laura Marholm is not interested in that which makes those women famous but tries to show a modern type of woman, her way of feeling and expressing emotions. This is something that comes up in their lives regardless of all the theories that they tried to develop in order to explain their way of living, regardless of ideas which they fought for, regardless of all the successes that in fact chained them more than anonymity could. The author notes that that is also the main premise of her book; she claims that all women suffered because of an internal clash that came to light only with and because of the feminist movement, the dichotomy between reason and the dark foundation of women’s nature. She concludes that the lives of most women got ruined because of that clash.

A contemporary woman who wants to break free on her way to independence is trying to escape from her life, Marholm writes. This sort of woman tries to reject taking care of someone, usually this implies being a mother, she tries to untie her knots with partners, but she also attempts to reject her idea that as a woman she is not a complete personality. However, this way, she, not knowingly, also banishes her femininity. The author supports her claims with poetic comparisons saying that modern women get stuck in front of the doors of their inner temple and thus don’t hear the sounds of secret worship celebrations; rather, they tremble in sterile dread and yearn for stimulating pleasures they excluded themselves from. They look for solutions, for a way out of this clashing state of being: some push the doors open and enter and this way, once again, belong to the world of men. Others stay outside and feel miserable. Laura Marholm also states that all of the women she wrote about were individualists and that was the cause of their demise.

However, they were not consistent and persistent enough in this individualistic stance, they were looking for a way out, in fact. Some found that which frees the tied-up individuality, others didn’t. That was because, as the author observes, her most prominent contemporaries are very selective when it comes to men, and on the other hand, contemporary men are rebellious and don’t have faith when it comes to searching for women. Marholm completes her introduction by saying that she identified some secret parts of the female soul with her six women and she is therefore offering this insight for those who didn’t have that opportunity. In the second edition she wrote that she would like her book to initiate the creation of new books which would reveal also other parts of a contemporary woman: her essence in relation to Zeitgeist, her needs, everything that was concealed, her suffering, her mistakes and her aspirations and hopes for the future.

In the introduction, Marholm lucidly formulates the problem that many women who wanted to live the life of a “new woman” faced; namely, the life of an independent person who freely expresses her world views, is independent and feels equal to men, but at the same time doesn’t want to deny her femininity. By saying that Marholm enters the feminist discourse that is based on a paradox, namely she tries to introduce an anti-patriarchal discourse while stemming from femininity. She understands her sex as equal to men and not as a subjugated one. We are dealing with female genealogy in which the maternal role seems to be the dominating one. This is something that Marholm connects with Luce Irigaray (Witt-Brattström, 149). The author states already in the introduction that she is not interested in the question of what a woman’s life is like if a woman doesn’t fulfil her talents professionally, but rather what it means for a successful woman to be a mother and a woman who loves and is loved. Moreover, she also stresses the importance of women’s fulfilment in sex and the deepening of her sexual relations. The problematic part of her work are surely her individual judgements on women’s artistic expression, as they are written down as claims that are valid for all women.

Read the excerpt from the book.

Laura Marholm: Modern Women

Among the group of celebrated women-thinkers: Leffler, Ahlgren, Agrell, &c., who criticised love as though it were a product of the intelligence, followed by a crowd of maidenly amazons, there suddenly appeared an author named Amalie Skram, whom one really could not accuse of being too thoughtful. It is true that in her first book there was the intellectual woman and the sensual man, and a seduced servant girl, grouped upon the chess-board of moral discussion with a measured proportion of light and shade that was the usual method of treating the deepest and most complicated moments of human life. But this book contained something else, which no Scandinavian authoress had ever produced before; her characters came and went, each in his own way, every one spoke his own language and had his own thoughts, there was no need for inky fingers to point the way, life lived itself, and the horizon was wide with plenty of fresh air and blue sky there was nothing cramped about it like the wretched little extract of life to which the other ladies confined themselves. There was a wealth of minute observation about this book, brought to life by careful painting and critical descriptions, a trustworthy memory and an untroubled honesty; one recognised true naturalism below the hard surface of a problem novel, and one felt that if her talent grew upon the sunny side, the North would gain its first woman naturalist who did not write about life in a critical, moralising, and polemical manner, but in whom life would reveal itself as bad and as stupid, as full of unnecessary anxiety and unconscious cruelty, as easy-going, as much frittered away and led by the senses as it actually is.

Among the group of celebrated women-thinkers: Leffler, Ahlgren, Agrell, &c., who criticised love as though it were a product of the intelligence, followed by a crowd of maidenly amazons, there suddenly appeared an author named Amalie Skram, whom one really could not accuse of being too thoughtful. It is true that in her first book there was the intellectual woman and the sensual man, and a seduced servant girl, grouped upon the chess-board of moral discussion with a measured proportion of light and shade that was the usual method of treating the deepest and most complicated moments of human life. But this book contained something else, which no Scandinavian authoress had ever produced before; her characters came and went, each in his own way, every one spoke his own language and had his own thoughts, there was no need for inky fingers to point the way, life lived itself, and the horizon was wide with plenty of fresh air and blue sky there was nothing cramped about it like the wretched little extract of life to which the other ladies confined themselves. There was a wealth of minute observation about this book, brought to life by careful painting and critical descriptions, a trustworthy memory and an untroubled honesty; one recognised true naturalism below the hard surface of a problem novel, and one felt that if her talent grew upon the sunny side, the North would gain its first woman naturalist who did not write about life in a critical, moralising, and polemical manner, but in whom life would reveal itself as bad and as stupid, as full of unnecessary anxiety and unconscious cruelty, as easy-going, as much frittered away and led by the senses as it actually is.

/…/ Amalie Skram’s talent culminated in ” Lucie.” In this book we see her going about in an untidy, dirty, ill-fitting morning gown, and she is perfectly at home. It would scandalise any lady. Authoresses who struggle fearlessly after honest realism like Frau von Ebner-Eschenbach and George Eliot might perhaps have touched upon it, but with very little real knowledge of the subject.

Amalie Skram, on the other hand, is perfectly at home in this dangerous borderland. She is much better informed than Heinz Tovote, for instance, and he is a poet who sings of women who are not to be met with in drawing-rooms. She describes the pretty ballet girl with genuine enjoyment and true sympathy; but the book falls into two halves, one of which has succeeded and the other failed. Everything that concerns Lucie is a success, including the part about the fine, rather weak-kneed gentleman who supports her, and ends by marrying her, although his love is not of the kind that can be called “ennobling.” All that does not concern Lucie and her natural surroundings is a failure, especially the fine gentleman’s social circle, into which Lucie enters after her marriage, and where she seems to be as little at home as Amalie Skram herself. Many an author and epicurean would have hesitated before writing such a book as ” Lucie.” But Amalie Skram’s naturalism is of such an honest and happy nature, that any secondary considerations would not be likely to enter her mind, and in the last chapter the brutal naturalism of the story reaches its highest pitch. In the whole of Europe there are only two genuine and honest naturalists, and they are Emile Zola and Amalie Skram. Her later books take, for instance, her great Bergen novel, ” S. G. Myre,” ” Love in North and South,” ” Betrayed,” &c. are not to be compared with the three that we have mentioned. They are naturalistic, of course, their naturalism is of the best kind, they are still un coin de la nature, but they are no longer entirely vu a travers un temptrament. They are no longer quite Amalie Skram. Norwegian naturalism we might almost say Teutonic naturalism culminated in Amalie Skram, this off-shoot of the Gallic race. Compared with her, Fru Leffler and Fru Ahlgren are good little girls, in their best Sunday pinafores; Frau von Ebner is a maiden aunt, and George Eliot a moralising old maid. All these women came of what is called ” good family,” and had been trained from their earliest infancy to live as became their position. All the other women whom I have sketched in this book belonged to the upper classes, and like all women of their class, they only saw one little side of life, and therefore their contribution to literature is worthless as long as it tries to be objective. Naturalism is the form of artistic expression best suited to the lower classes, and to persons of primitive culture, who do not feel strong enough to eliminate the outside world, but reflect it as water reflects an image. They feel themselves in sympathy with their surroundings, but they have not the refined instincts and awakened antipathies which belong to isolation. Where the character differs from the individual consciousness, they do not think of sacrificing their soul as a highway for the multitude, any more than their body a la Lucie to the commune bonunt.

Source: Modern women; an English rendering of Laura Marholm Hansson’s ‘Das buch der frauen’

Activity

Find in the text some examples of Marholm’s “appealing and seducible as well as contradictory” (Brantly 1991: 107) language.

Who does Marholm compare Skram with? How do you perceive Skram after reading this comparisons?

How does Marholm touch upon class identity of women writers? How does she connect it with authorial freedom?

Marholm’s books have been forgotten for decades. How do you see the importance of her work? Do you think that the problems discussed in her books are still present in today’s society?

Do you know the term “écriture féminine“? Do you see any connections between this term and Marholm’s view on women writers’ creative process?

Further Reading

Mihurko Poniž, Katja. Ambiguous views on femininity in the writings of two “New Women” in the fin de siècle : Zofka Kveder’s inspirational encounters with Laura Marholm’s modern women.

References:

Brantly, Susan, 1991. The life and writings of Laura Marholm. Basel; München: Helbing & Lichtenhahn.