1 Corpus in Focus: A Guide to Use Corpus in EFL/ESL Classroom

Abdulkadir Abdulrahim

Çukurova University, ELT Department, Adana/Turkey

abandulrahim1@gmail.com

Corpus linguistics and corpus-based studies are the current trending topics in the fields of foreign language teaching and learning. As the definition suggests, a corpus refers to a collection of written materials or specific sections of written and spoken materials that can be used to carry out a broader linguistic analysis (Sinclair, 1991). According to Meunier “The last factor accounting for the lukewarm of corpora in the classroom is the lack of empirical studies exploring the actual impact of corpus methods on the learning outcomes” (Meunier, 2011: 463). The number of publications on corpus linguistics is rather significant, however, “despite the progress that has been made in the field of corpus linguistics and language teaching, the practice of ELT has so far been largely unaffected by the advances of corpus research” (Römer, 2006: 121). Thus, adopting corpus in EFL classrooms will provide a chance for both teachers and students to become acquainted with the foreign language, and will aid in introducing this foreign language into the classroom, to enhance a more effective language learning environment, especially in those countries where English is not the national or official language.The use of linguistic corpora in foreign language classes and their impact on changing the perspectives of language teachers and learners are the main topics of this study.

Keywords: Corpus (corpora), Language Classroom, EFL Learners, Language Teaching and Learning

- Introduction

A corpus refers to a set of language samples that are carefully chosen and arranged based on specific linguistic standards to serve as a representation of a language. A computer corpus, on the other hand, is a standardized collection of language pieces that are encoded in a consistent manner to allow for easy access and retrieval. Additionally, the sources and background of each language component are well-documented (Sinclair 1996). According to Granger (2002), corpus linguistics is a linguistic methodology, which employs electronic collections of naturally occurring texts. Despite the fact that corpus linguistics is not a new branch of linguistics, its authenticity makes it a particularly effective methodology that provides innovative perspectives in language study. (Granger, 2002).

Similarly, Leech (1991) defines corpus linguistics more like a methodology rather than a stand-alone scientific domain. According to him, the development of corpus linguistics has led to the emergence of sophisticated IT tools for searching and annotating electronic textual data, such as taggers, parsers and concordancers. (Leech, 1992). He also claims that “it is from these tools, as much as from the availability of abundant text data, that Corpus Linguistics has derived its special character and its unprecedented power to reveal the characteristics of real language use” (Leech, 1992, p. 158). For this reason, Corpus Linguistics could be considered a methodologically oriented branch of linguistics.

Within the same line of reasoning, Leech (1992), McEnery & Wilson (1996), McEnery et al. (2006) refer to it as a methodology, whereas Hoey (1997: 6) talks about “the route into linguistics”. Biber et al. (1998) defined it as “an approach”, and Scott & Thompson (2001: 36) describe corpus linguistics as “a means for accessing resources”.

- Learner corpora

Nesselhauf (2004b: 40) defines learner corpora as “systematic computerized collections of texts produced by language learners”. Learner corpus research is a relatively recent, yet highly dynamic, branch of corpus linguistics, that emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Learner corpora, which can be roughly defined as electronic collections of texts produced by language learners, have been used to fulfill two distinct, though related, functions: firstly, they can contribute to Second Language Acquisition theory by providing a better description of interlanguage communication (e.g. transitional language produced by second or foreign language learners) and a better understanding of the factors that influence it. Secondly, they can be used to develop pedagogical tools and methods that better cater to the needs of language learners (Granger, 2008).

According to Ludeling and Kytö (2008) corpus databases not only provide opportunities for linguistics research, but they are also useful sources for language teaching and learning research.

Bernardini (2004) indicates that recent technological advancements, such as high-capacity hard drives, fast processors in computing technology, and the possibility to create, download, buy, and/or access online texts have resulted in corpora being widely available in a more convenient and feasible way. According to him “corpus has become less of a buzzword and more of a necessary, acknowledged reference source for students, linguists, language professionals (teachers, translators, technical writers, lexicographers, etc.)” (Bernardini, 2004: 21).

Sinclair describes learner corpora as “electronic collections of authentic FL/SL textual data assembled according to explicit design criteria for a particular SLA/FLT purpose. They are encoded in a standardized and homogeneous way and documented as to their origin and provenance” (Sinclair, 1991: 2).

- Corpus and ELT

When we discuss the use of corpora in language teaching and learning, we refer to both corpus tools, i.e. the current collections of texts and software packages, and corpus methodologies, i.e. the analytical approaches employed in the corpus analysis process. A relevant distinction may be established in the context of language teaching and learning between direct and indirect uses of learner corpus linguistics (Römer, 2008; Leech 1997).

As Barlow notes, “the results of a corpus-based investigation can serve as a firm basis for both linguistic description and, on the applied side, as input for language learning” (1996: 32). As stated in Römer “Large general corpora have proven to be an invaluable resource in the design of language teaching syllabi which emphasize communicative competence (cf. Hymes 1972, 1992) and which give prominence to those items that learners are most likely to encounter in real-life communicative situations” (2008: 114).

The contents of this new, corpus-driven “lexical syllabus” are “the commonest words and phrases in English and their meanings” (Willis, 1990:124).

Another significant advantage for language teachers who employ corpora is the immediate accessibility of authoritative information about the language. According to a recent survey on teachers’ needs (Römer, forthcoming), teachers often seek native speakers’ advice on specific language issues. Computer corpora have been described as “tireless native-speaker informant[s], with rather greater potential knowledge of the language than the average native speaker” (Barnbrook, 1996: 140), as a result, they may be a useful tool to extract linguistic and language information.

Learner corpora analysis aids in our understanding of the process of second language acquisition and development. As suggested by O’Keeffe et al. (2007) this might transform the “long-held” notions of education and pedagogy, by bridging the gap between the cognitive science of language and other fields, such as sociolinguistics and translation. According to Aston (2000), student corpora studies have aided syllabus design by providing insights into “the demands of distinct student groups” (Meunier, 2002:125).

The application of corpus studies to material development in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) has revealed the insufficiency of traditional prescriptive grammar. Instead, corpus-based descriptive grammar approaches, such as the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English (Biber et al., 1999), have been used to provide a corpus-informed perspective and information on frequencies. However, it should be noted that although corpus-based grammars have some potential for language skill development, they do not offer the same opportunities as corpora in terms of “identify – classify – generalize” learning based on language experience. This limitation can be overcome by implementing corpus-based teaching approaches, such as the emerging Data-driven Teaching techniques, which have great potential for enhancing learning outcomes, especially in non-institutional settings where autonomous learning is necessary.

- Corpus-based Versus Corpus-driven studies

It is not always straightforward to distinguish between corpus-based and corpus-driven studies. McEnery and Hardy (2012) proposed a subdivision in this regard: corpus-based studies typically use corpus data in order to investigate a theory or a hypothesis, in order to validate, refute or refine it. Contrarily, the corpus-driven approach does not consider corpus linguistics as a method, claiming instead that the corpus itself should be the sole source of language-related hypotheses.

Simply put, those who adopt the ‘corpus-based approach’ (McEnery et al., 2006) use corpus linguistics to test existing theories or frameworks based on the corpus evidence.

Corpus linguistics serves as a remedy to language misuse (in terms of error analysis) and it provides the representation of authentic language usage; thus, corpus-based studies are studying that shade light as evidence of the language’s existence and how the language is being used by the members of the community or is being used by a language learner. Moreover, Corpus-based studies give some overviews of language progress, the future of a language, linguistic information about the languages, and the feature of the language used in the past such as diachronic and synchronic studies.

As Widdowson observes that there has been a flourishing of “dictionaries and grammatical descriptions which are corpus-based, and which chart the patterns of the contemporary usage of English” (Widdowson, 2008: 357). Unlike corpus-based studies, the corpus-driven approach to language teaching studies uses corpus data as a tool and resource to shape the way, technique, or methods of language teaching. Johns (1991a, 1991b) notably used the corpus-driven approach to develop an effective language learning methodology: data-driven learning (DDL). In DDL, the language learner is also a linguistic researcher who uses corpora to explore and make sense of language usage patterns in order to better learn the language. To sum up, while the corpus-based approach separates theory from data, and standardizes data to fit the theory, the corpus-driven approach uses corpora as a tool to formulate linguistic theories.

- Error Analysis in ELT

Error analysis (EA) has had a significant impact on research in Second Language Acquisition (SLA), with Corder’s model of error analysis (1967) gaining popularity over traditional Contrastive Analysis. Corder emphasizes the usefulness of error analysis, stating that errors are indicative of an L2 learner’s language performance, and identifying these errors can aid in developing effective learning strategies and techniques for students. Corder classifies errors into four categories. However, current EA practices differ from those of the 1970s. Today’s EA focuses on contextualized errors, considering the context of use and linguistic context (co-text). Linguistic items with errors can be presented along with correct examples in sentences, paragraphs, or entire texts. Interlanguage errors are a crucial part of EFL learning processes and differ from mistakes, as they are systematic and provide clues about learners’ learning strategies and processes. Detecting errors requires an arduous process of deciding whether the semantic content and linguistic form of learners’ communicative performances deviate from the norms. Learner corpora offer a more dependable option to examine naturally occurring learner errors, assisting researchers in pinpointing error typologies of learners from different native language backgrounds. A specialized corpus can be utilized to advise language teaching, focusing on specific points, genres, and sub-genres. The two methodological approaches, Computer-aided Error Analysis, and Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis are generally involved in the linguistic exploitation of learner corpora. Computer-aided error analysis generates comprehensive lists of specific error types, counts and sorts them in various ways, and views them in context. Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA) is a contrastive method of analyzing quantitative and qualitative data between native and non-native varieties or between different non-native varieties.

- Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA)

Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA) compares language learner and native speakers’ data regarding the target language, or the learner’s L1. The first type of comparison attempts to evaluate the level of under- or overuse of linguistic features in language learners. The second type tries to reveal the L1 linguistic transfer or interference.

According to Lorenz (1999), the NS/NNS comparisons aim to shed light on the characteristics of non-native speakers’ writing and speech, by comparing them with the linguistic data of native and non-native corpora.

As already mentioned, CIA also compares NNS/NNS; in doing so, “researchers improve their knowledge of interlanguage” (Lorenz, 1999: 12). Moreover, comparing the data of learners from different L1 backgrounds, may reveal interlanguage universals, shared by various learner populations, that can be developmental and L1 dependent. For example, in their study on connectors, Granger and Tyson determine that the overuse of sentence-initial connectors is an interlanguage and developmental characteristic of the three learner populations, namely French, Dutch, and Chinese. The individual connectors that have a wide variety of use among these learner groups provide evidence for interlingua characteristics (Granger & Tyson, 1996).

According to the contrastive analysis (CA) hypothesis by Dagneaux et al., (1998), communication strategy-based errors may occur when the L2 learner seeks to convey a spontaneous speech with an inadequate grasp of the linguistic system of the target language. In fact, L2 learners tend to adopt “approximation” strategies, by using a near-equivalent L2 item they have previously learned, when they lack the demanded and correct form. In this regard, Dagneaux et al. (1998) provide a number of examples related to Chinese L2 language learners; in particular, they note the use of synonyms (“decide” instead of “determine”), superordinate words “flower” instead of “rose”).

Although the fundamentals of EA are extremely important, this procedure has methodological flaws. Computer-Aided Error Analysis (CEA) provides comprehensive lists of specific error types, counting and sorting them in various ways, and tagging them in context along with their non-errors instances. Completing the gaps in traditional EA, CEA is a powerful technique that aids ELT teachers and syllabus designers in developing innovative and creative pedagogical tools.

- Corpus-driven Activities

7.1 Speaking Skills

Corpus-driven speaking activities could help EFL/ESL learners develop their oral communication skills, critical thinking skills, and digital literacy skills. Below are some examples of speaking activities that can be used in the EFL classroom:

- Discussions: Students can use data and statistics to support their arguments in a debate. For example, students can debate topics such as climate change or social media usage, and use data to support their positions. This can help them to develop critical thinking skills and oral communication skills.

- Interviews/Talks/Conversations: Students can use data to interview each other on a variety of topics, such as personal interests or career goals and hobbies and use data to find common interests. This can help them develop oral communication skills and digital literacy skills.

- News Reports: Students can use data and statistics to create news reports on current events. For example, students can report on a natural disaster and use data to explain the impact on the local community. This can help them develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and oral communication skills.

- Presentations: Students can use data and statistics to create presentations on a variety of topics, such as health, education, or technology. For example, students can analyze data on the use of technology in education and present their findings to the class. This can help them to develop research skills and oral communication skills.

- Role-plays/Drama: Students can use data and statistics to role-play different scenarios, such as job interviews or business meetings. For example, students can role-play a job interview and use data to explain why they are the best candidate for the position. This can help them develop oral communication skills and digital literacy skills.

7.2 Vocabulary Development

Corpus-driven vocabulary activities are a great way to help EFL/ESL learners to expand their vocabulary in a meaningful and engaging way. These are some examples of vocabulary activities that can be used in the EFL classroom:

- Word Clouds: Students can create word clouds using a tool like Wordle, Scrabble, Tagxedo, etc. to visualize and analyze the most common words in a text. This can help them to identify and learn new vocabulary related to a specific topic, such as technology or education.

- Vocabulary Profiles: Students can use a corpus or authentic texts to create vocabulary profiles of keywords related to a specific topic and use it to learn new vocabulary and use it in context.

- Bingo: Students can create their own bingo cards using vocabulary words related to a specific topic and use them to practice speaking and listening skills.

- Word Match: Students can use a corpus or authentic texts to match vocabulary words with their meanings and use them to practice reading and writing skills.

- Quiz: Students can use online quiz tools like Kahoot, Bamboozle, or Quizlet to practice, review vocabulary words related to a specific topic, and use it to practice listening and reading skills.

7.3 Writing Skills

Corpus-driven writing activities can help EFL/ESL learners to develop their writing skills and critical thinking skills. Here are some examples of activities that could be used in the EFL Writing classroom:

- Argumentative Essays: Students can use data and statistics to support their arguments in an essay. This can help them to develop critical thinking skills and writing skills.

- Opinion Writing: Students can use data and statistics to write opinion pieces on a variety of topics, such as politics or education. This can help them to develop research and writing skills.

- Reports: Students can use data and statistics to write research reports on a variety of topics, such as health or technology. For example, students can write a research report on the effects of social media on mental health and use data to support their findings. This can help them develop research skills and writing skills.

- Creative Writing: Students can use data and statistics to inspire their creative writing. For example, students can write a short story based on data about a specific culture or community. This can help them develop their imagination and writing skills.

- Speeches: Students can use data and statistics to prepare persuasive speeches on a variety of topics, such as the environment or social justice. This can help them develop public speaking skills and critical thinking skills.

7. 4 Reading Skills

Corpus-driven reading activities can help EFL/ESL learners to improve their reading comprehension skills, critical thinking skills, and digital literacy skills. Examples of reading activities that could be used in the EFL classroom are reported belw:

- Graphic Analysis: Students can analyze infographics to understand data and statistics related to a specific topic and to develop critical thinking skills.

- News Article: Students can analyze news articles to understand current events and develop their reading comprehension skills. For example, students can read articles about the impact of technology on education and use them to answer comprehension questions and develop critical thinking skills.

- Reading Comprehension: Students can practice reading comprehension skills by using data-driven reading comprehension exercises. This helps to develop critical thinking skills.

- Summarizing: Students can practice summarizing skills by reading articles and summarizing key points.

- Online Questionnaires: Students can use web questionnaires to explore a topic in-depth and develop their reading and research skills. For example, students can complete a web quest on a specific culture and use data to answer comprehension questions and develop critical thinking skills.

7.5 Listening Skills

Corpus-driven listening activities are activities that use data as a basis for listening practice. The goal of these activities is to encourage learners to develop their listening skills by using data as a starting point for listening comprehension and analysis. Below are some examples of listening activities:

- Podcasts: Students may listen to podcasts on various topics, such as news, science, or history, and then discuss the content as a group. This can help them to develop their comprehension skills and encourage them to use new vocabulary and expressions.

- TED Talks: TED Talks are informative and engaging presentations on a wide range of topics. Students may watch a TED Talk and then discuss the content and ideas presented in the talk.

- News reports: Students may listen to news reports on various topics, such as politics, economics, or culture, and then discuss the main points and themes of the report.

- Songs/Poetry: Songs can be a great way to practice listening skills and learn new vocabulary and expressions.

- Speeches/Talks: Students may listen to speeches given by famous figures, such as politicians, activists, or artists, and then analyze the content and style of the speech.

- Implementation of Corpus in ELF Classroom: speaking procedure

In this paragraph, I will introduce an English L2 lesson, supported by the use of corpora.

After the language teacher has introduced the topic of the lesson, a brainstorming session follows, to assess the students’ background knowledge about the topic under discussion.

Subsequently, the teacher presents the L2 language learners with a sample sentence or vocabulary extracted from native and non-native corpora, in order to give them some clues and ideas on how the language is authentically used, and invite the students to try to use these models to create examples of sentences.

In this way, the students will be able to see the differences between the production of native and non-native speakers and, according to my predictions, this will help them to use the language effectively and fluently.

When the aforementioned activities are completed, the teacher asks the students to practice conversation in groups or pairs, utilizing the corpus data they learned in class, in order to increase their awareness and prepare them to communicate fluently in everyday situations, inside and outside the classroom.

I think it is helpful to provide the corpus analysis data to the L2 learners so that they can determine which one is more appropriate between learner and native language corpora. In this way, the corpus data will guide the students toward success in learning a second language.

In my opinion, when using data from different corpora, the dictionary is unnecessary, since students may be able to comprehend how grammatical structures and words are used in a different context. At the same time, Aijmer reports “Several informants pointed out that it took a too long time to look up words in dictionaries and that they often wanted to consult a native speaker. However, most teachers did not see the consultation of one of the major language corpora as an alternative or supplement to the dictionary or grammar.” (Aijmer, 2009: 4). So, the students have to be able to check and use grammar books and dictionaries in different ways and contexts, depending on the content of the assigned topic.

- Some Sample Activities

English as foreign/second language teachers and learners could benefit from the following activities in their language classroom. These activities are adopted from Cambridge Learner Corpora, Contemporary Corpus of American English (COCA), and British National Corpora (BNC) which serve to provide a sample of authentic language used by native and non-native users.

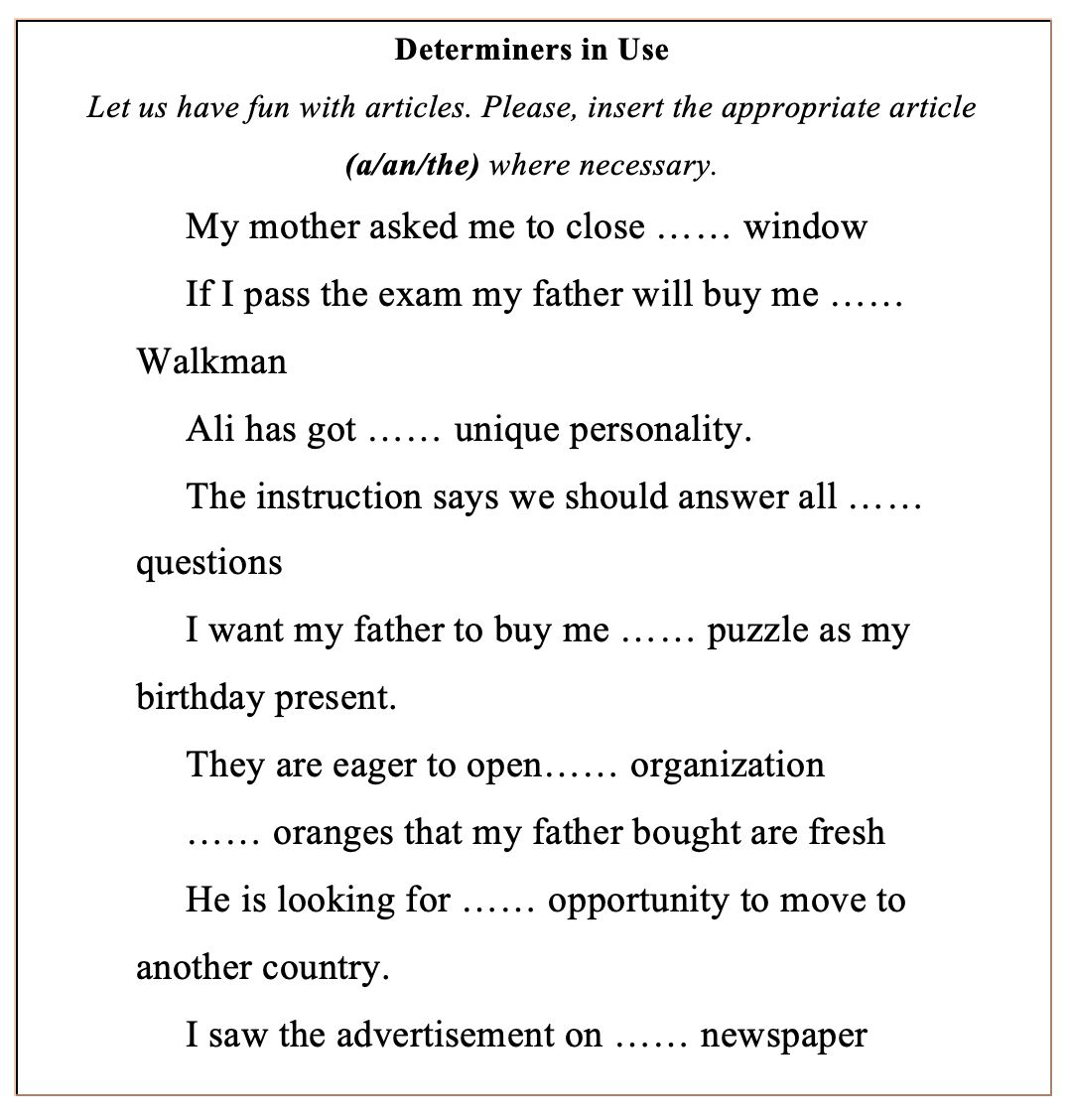

9.1 Activity 1 – Fill in the Blank

This activity provides teachers and learners with the opportunity to see how language is used and helps them to practice their knowledge of English determiners.

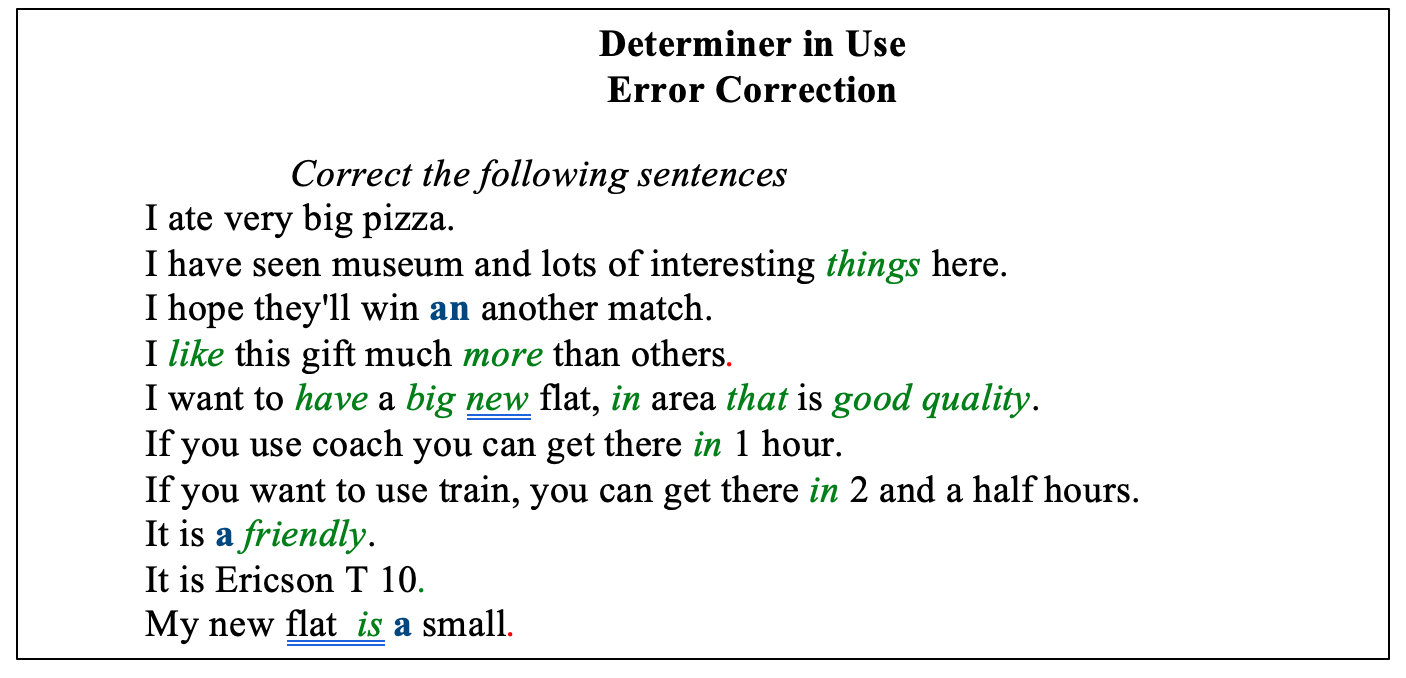

9.2 Activity 2 – Error Analysis

In this activity, learners will be able to see the wrong usage of English determiners and they have the chance to learn them by correcting the errors found in the sentences.

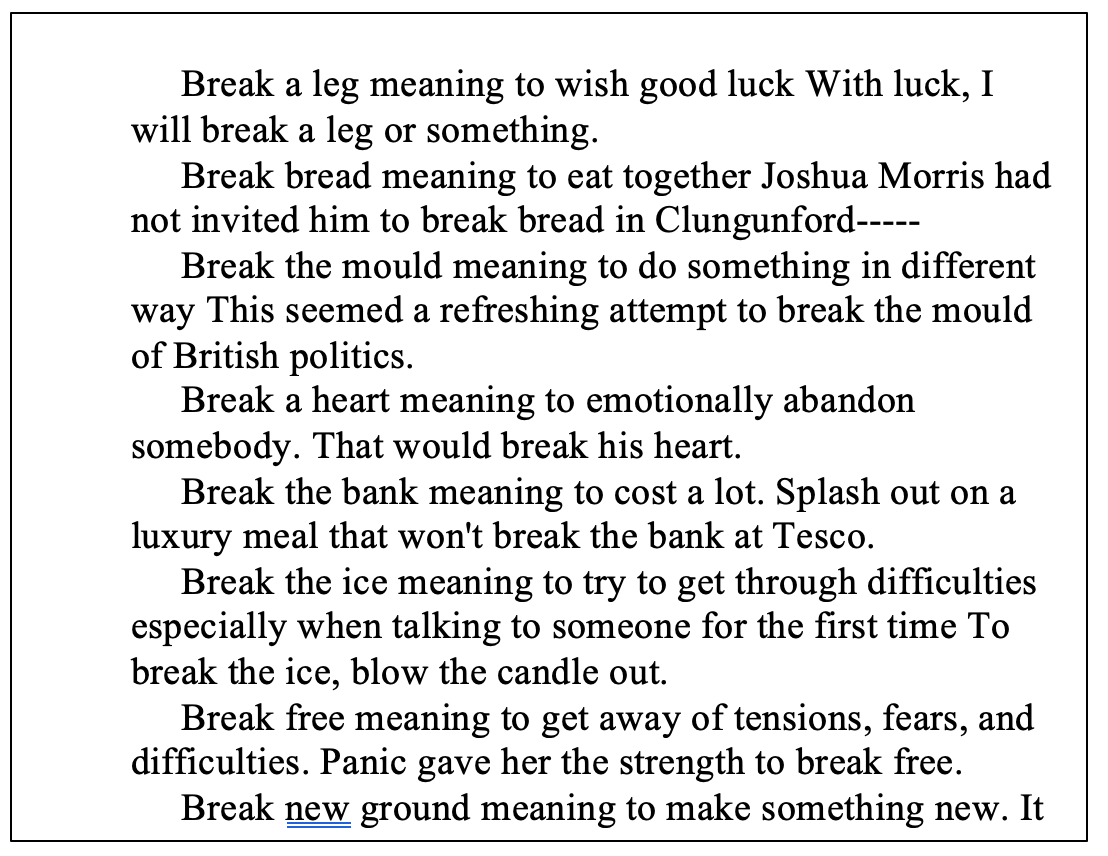

9.3 Activity 3 – Vocabulary development

After training students on how to use online corpora, you can ask them to search for the idiomatic expressions and analyze the concordance lines to see how these idioms are contextualized and used by native speakers. Following are some idiomatic expressions with the verb break.

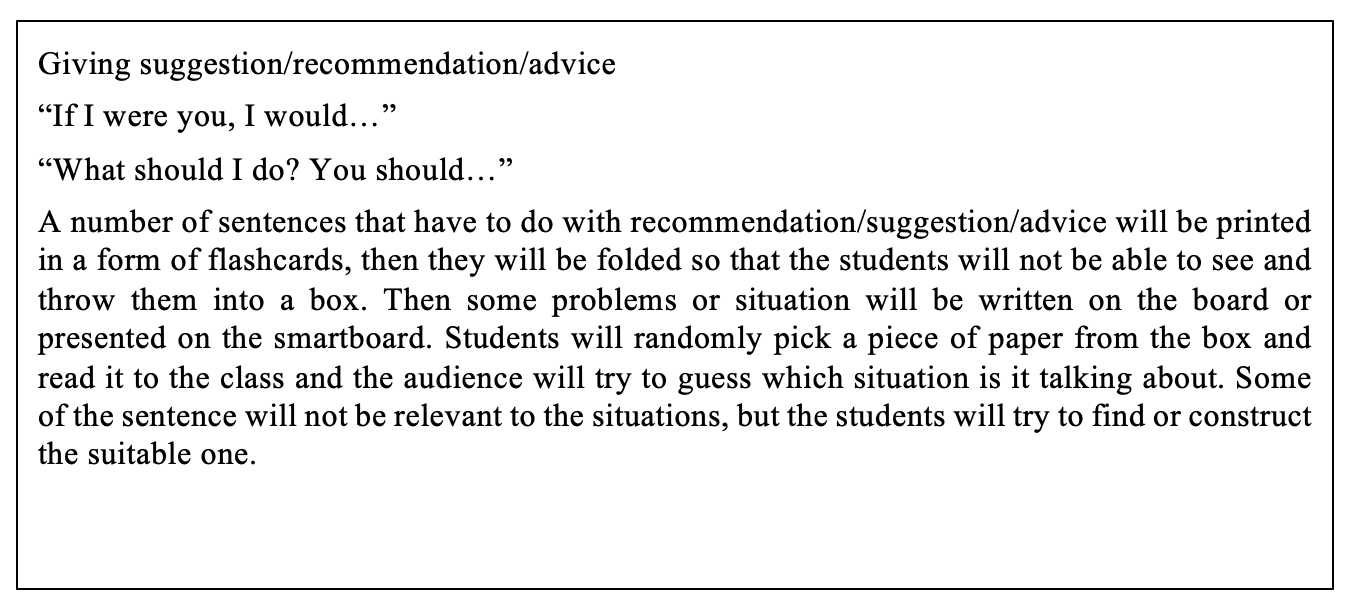

9.4 Activity 4

This activity will teach the students how to use the modal verbs and their context of use.

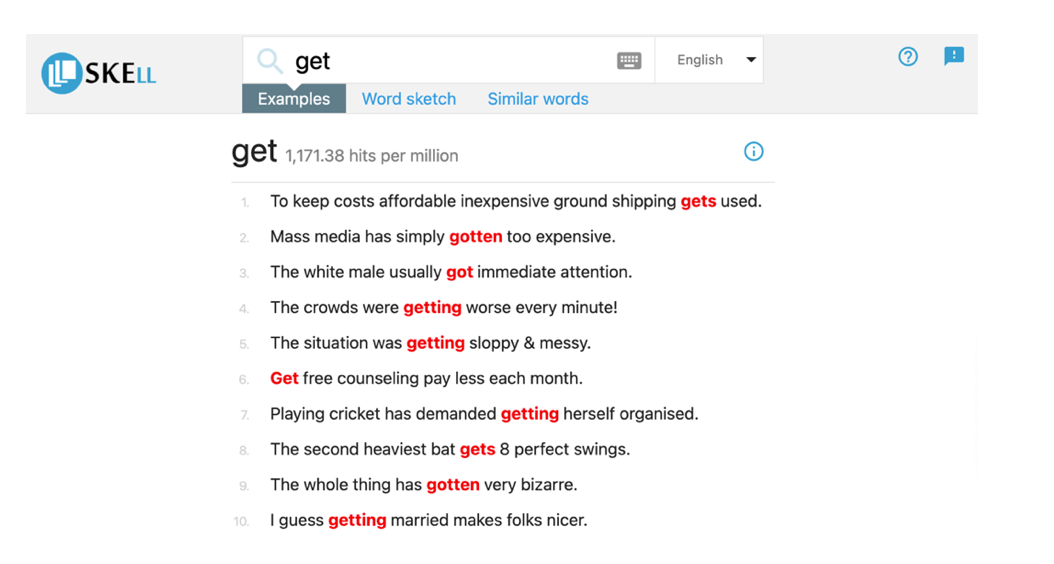

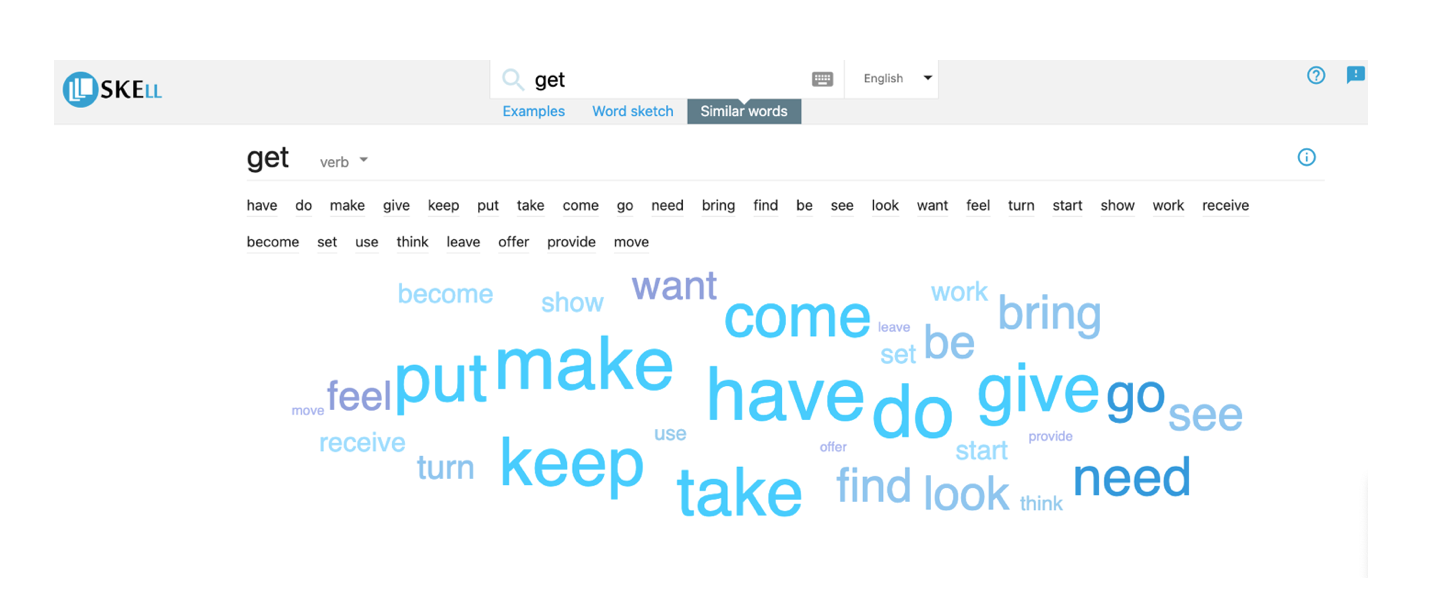

9.5 The use of SKELL

Teachers and learners can benefit from using Sketch Engine for Language Learning (SKELL). It is a web tool that provides authentic samples of language use for language teachers and learners. It could be used to search for word usage, concordance, collocations, etc.

For instance, “get” can be used in a different context. Figure 1 below shows one of the possible applications of SKELL.

Figure 1. Source: https://skell.sketchengine.eu/#result?f=thesaurus&lang=en&query=get.

Figure 2. Source: https://skell.sketchengine.eu/#result?f=thesaurus&lang=en&query=get.

- Conclusion

Language learning has advanced significantly over the past few years as a result of rapid technological advancement. In fact, corpus linguistics used in teaching and learning allows learners and teachers of L2 languages to quickly access language samples, spoken by native and non-native speakers. Several language learning resources, such as textbooks and dictionaries, may now be readily created and updated thanks to corpus linguistics. Moreover, the classroom environment becomes more engaging and interactive, and this improves language acquisition.

It should not be noted that a corpus is more than just an online computer-based repository of accessible data; however, a common dictionary, an encyclopedia or a library book collection could also be considered a corpus of texts. Turkish EFL classroom activities might be implemented through the students’ manuals and books, and through essays written by teachers and researchers.

In language classes, using corpus-based and corpus-driven materials improves learning and promotes student autonomy.

If the activity has proved useful and successful in terms of students’ language learning, it is up to the teachers and researchers to spread the use of corpus-based materials. The sample activities described in this paper show that corpus-related activities may be simply adopted in a language classroom, breaking the traditional monotony.

References

Aijmer, K. (2009). Corpus and Context. Investigating Pragmatic Functions in Spoken Discourse. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 14(3), 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.14.3.06aij

Aston, G. (2002). The Learner as Corpus Designer” In Teaching and Learning by Doing Corpus Analysis. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004334236_004

Barlow, M. (1996). Corpora for Theory and Practice. In International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1(1), 1-37.

Barnbrook, G. (1996). Language and Computers. A Practical Introduction to the Computer Analysis of Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bernardini, S. (2004). Corpus-aided language pedagogy for translator education (pp. 97–111). https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.59.08ber

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use. Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., & Reppen, R. (2016). The Cambridge Handbook of English Historical Linguistics.

Cheng, W. (2011). Exploring corpus linguistics: Language in action. Routledge.

Corder, S. P. (1975). Error Analysis, Interlanguage and Second Language Acquisition. Language Teaching, 8(04), 201. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800002822

Dagneaux, E., Denness, S., & Granger, S. (1998). Computer-aided error analysis. System, 26(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(98)00001-3

Dela Rosa, J. P. O., & Arguelles, D. C. (2016). Do Modification and Interaction Work?–A Critical Review of Literature on the Role of Foreigner Talk in Second Language Acquisition. Journal on English Language Teaching, 6(3), 46-60. https://doi.org/10.26634/jelt.6.3.8178

Granger, S. (2004). Computer Learner Corpus Research: Current Status and Future Prospects. Applied Corpus Linguistics: A Multidimensional Perspective (Language and Computers), 52, 123–145.

Granger, S. (2009). The contribution of learner corpora to second language acquisition and foreign language teaching: A critical evaluation. January 2009, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1075/scl.33.04gra

Granger, S. (2012). How to use Foreign and Second Language Learner Corpora. In Research Methods in Second Language Acquisition: A Practical Guide (Issue November). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444347340.ch2

Granger, S., & Meunier, F. (2008). Phraseology: An interdisciplinary perspective. America, 422. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.139

Granger, S., Hung, J., & Petch-Tyson, S. (2002). Computer learner Corpora, Second Language Acquisition and Foreign Language Learning. Language Learning & Language Teaching, 258.

Hymes, D. (1972). On Communicative Competence. In: Pride, John B./Holmes, Janet (eds.), Sociolinguistics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 269-293.

Hymes, D. (1992). The Concept of Communicative Competence Revisited. In: Pütz, Martin (ed.), Thirty Years of Linguistic Evolution. Studies in Honour of Rene Dirven on the Occasion of his Sixtieth Birthday. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 31-57.

Lüdeling, A., & Merja, K. (Eds.). (2008). Corpus linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

McEnery, T., & Hardie, A. (2012). Corpus linguistics: Method, theory and practice. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics, xv, 294 p. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

McEnery, T., & Wilson, A. (2001). Corpus Linguistics: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=nwmgdvN_akAC&pgis=1

Meunier, F., Cock, S. D., Gilquin, G., & Paquot, M. (2011). A Taste for Corpora. In honour of Sylviane Granger. Studies in Corpus Linguistics, 45, 313.

Nesselhauf, N. (2004). Learner corpora and their potential for language teaching. In J. Sinclair (Ed.), How to use corpora in language teaching (pp. 125–157). Amsterdam: John BenjaminsPublishing Company.

O’Keefe, A., McCarthy, M., & Carter, R. (2007). From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Römer, U. (2008). Corpora and language teaching. Corpus Linguistics, 1, 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2003.12.001

Scott, T. (2020). Higher Education’s Marketization Impact on EFL Instructor Moral Stress, Identity, and Agency. English Language Teaching, 14(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v14n1p99

Sinclair, J. M. (1991a). Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinclair, J. M. (1991b). Shared knowledge. In J. E. Alatis (Ed.), Georgetown University Round Table on Language and Linguistics 1991 (pp. 489–500). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Sinclair, J. M. (1996). The search for units of meaning. Textus, 9(1), 75–106

Widdowson, H. G. (2008). Text, context, pretext: Critical issues in discourse analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Willis, D. (1990). The Lexical Syllabus. A New Approach to Language Teaching. London: Harper- Collins.