11 Translanguaging in Corrective Feedback Provision as a Flexible Approach to Communicative Foreign Language Teaching and Learning: a semi-systematic literature review

Siqing Mu

Macao Polytechnic University, Faculty of Languages and Translation, Macau SAR, China

kelseymu@gmail.com

In recent years, a rise in research has validated the practice of translanguaging as a valuable and beneficial instructional approach. This pedagogy is considered practical as it supports the flexible and integrated use of linguistic and semiotic sources for meaning construction, fostering plurilingual competence, and aiding in foreign language teaching and learning. Translanguaging has been demonstrated to enhance student’s learning potential and engagement in bilingual and multilingual classrooms when feedback facilitates meaning exchange through negotiated involvement. Implementing translanguaging in feedback is increasingly recognized as a transformative pedagogy for efficient and responsive teaching and learning. By amalgamating the findings of recent studies, this study intends to elucidate the present situation of literature on the way in which translanguaging is approached in feedback across various educational contexts. A high-level scoping analysis was conducted using a semi-systematic approach, employing keywords, research objectives, study settings, and primary discoveries. Subsequently, a narrative review was compiled based on the inclusion criteria. Following the elimination of duplicates, the literature consisted of 22 peer-reviewed studies, published between 2017 and October 2022 and accessible in the two representative and sizable databases—— Scopus and Google Scholar. This review delineated the primary educational and research contexts where studies were undertaken, the research methodology employed in investigating pedagogic translanguaging in feedback practices, as well as the considerations and implications of translingual practices in corrective feedback that were highlighted as an enriched and encompassing communicative approach in foreign language classes.

- Introduction

In the last twenty years, translanguaging has emerged as a complex and multilayered term in applied linguistics, particularly in multilingual settings, possessing several polysemic connotations (Leung & Valdes, 2019: 359). The term is defined and elucidated by Li Wei in a broader sense,

Translanguaging is both going between different linguistic structures and systems, including different modalities (speaking, writing, signing, listening, reading, remembering) and going beyond them. It includes the full range of linguistic performances of multilingual language users for purposes that transcend the combination of structures, the alternation between systems, the transmission of information and the representation of values, identities and relationships. (2011: 1223)

In the renewal of the theoretical conceptualization of languages, translanguaging posits speaker’s multilingual resources as an entirety of repertoire, from which they are unlimited to “take on board bits of any language available in strategically diverse ways in order to achieve a (localized) communicative function” (Spotti & Blommaert 2017: 172). From a social perspective, translanguaging is “the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire without regard for watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named (and usually national and state) languages” (Otheguy et al., 2015:283). The theory directs attention to a dynamic process, in which multilingual speakers successfully negotiate meanings to meet social and cognitive demands through the application of a broad range of languages (García, 2009; García & Li, 2014).

While contextualized in pedagogical practices, translanguaging is viewed as a valuable language-as-resource orientation and treated as a new approach that allows learners to mobilize all their linguistic resources, lived experience, and language competence developed in L1 and other languages for meaning-making purposes (Nagy, 2018; Burton & Rajendram, 2019). It is worthwhile to differentiate the specificity of translanguaging from similar terms as “code-switching” (Li, 2018a), García and Li Wei point out the difference:

Translanguaging differs from the notion of code-switching in that it refers not simply to a shift or a shuttle between two languages, but to the speakers’ construction and use of original and complex interrelated discursive practices that cannot be easily assigned to one or another traditional definition of a language, but that make up the speakers’ complete language repertoire. (2014:22)

Hence, rather than simply an “alternation at the inter-clausal/sentential level” (Lin, 2013:195), translanguaging pedagogy goes in and beyond the original meanings of translanguaging itself, it leverages the complete language repertoire of the students and looks at the “different ways speakers learn and use their languages without comparing them with ideal native speaker of different languages” (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022:15). However, when considering translanguaging as a resource in L2 pedagogy, language alteration (i.e., combining two or more languages in learning) was understood as a type of translanguaging practices (Gort & Pontier, 2013). Accordingly, translanguaging can be implemented in a spontaneous/unplanned way when it is multilingual-learner-centered, or in a strategical/planned manner when a specific teaching methodology is designed or facilitated by the teacher (Cenoz, 2017). This pedagogic theory has sparked extensive research (e.g., Kahlin et al., 2021; Vattøy & Gamlem, 2020; Prada & Turnbull, 2018) that examines the theoretical and empirical aspects of translanguaging as a flexible language practice and a pedagogical strategy in diverse educational contexts. The application of translanguaging in language teaching seems pivotal in promoting the mainstream of bilingual or multilingual learning for several reasons: it encourages innovative and inclusive pedagogic approaches by capitalizing on learners’ language backgrounds; it seeks to improve their academic achievements; and it also strengthens learning outcomes through metalinguistic awareness sensibilization and communicative competence development.

Translanguaging as a resource helps to understand how languages can be conceptualized and practiced in L2 classrooms. Cenoz and Gorter (2020), Lewis et al. (2012), and Talavera (2017) suggested that teachers could apply pedagogical translanguaging and constructed avenues for improving language aptitude and awareness in the process of feedback provision, where corrective feedback (CF) is a predominant interaction-based activity in communicative language teaching and learning (Leeman, 2007). CF, defined as the teacher’s or peers’ response to erroneous learners’ utterances, has received considerable research attention over the past two decades. It is an essential element of communicative language teaching and learning in various second language (L2) classroom settings and has been shown to be effective in developing L2 writing skills (Li, 2010; Nassaji, 2017; Nassaji & Kartchava, 2020; Ha & Murray; 2020). In line with Elbow (1999), CF instructions should not be stuck to identifying “wrong language” (i.e., inadequate metalinguistic expressions or incorrect syntactic structures) and surface mistakes as crucial weaknesses in students’ writing, but rather, as Han (2002) and Bitchener & Ferris (2012) highlight, there is an increasing necessity of innovative pedagogical intervention involving CF to promote dynamic development in the target language, that can be practically designed at linguistic, syntactic, and lexical levels and practiced in L2 writing activities.

In recent times, a growing number of studies have endeavored to explore the theoretical and empirical association between translanguaging and CF (e.g., tutor’s CF, peer CF, automated CF) in class or remote language practices. In the execution of translanguaging, L2 students are enabled to “use the stronger language to develop the weaker language, thus contributing towards what could potentially be a relatively balanced development of a child’s two languages” (Cenoz & Gorter, 2020: 5). For instance, studies of Sun & Zhang (2022), Kim & Chang (2022), and Wang & Li (2022) situated translanguaging as a resourceful approach that was implemented in corrective feedback provisions, they suggested that using students’ L1 in feedback may more effectively help L2 learners understand their erroneous utterances and improve their performances on content and textual organization in L2 writings. Furthermore, the flexible use of L1 and L2 to offer specific linguistic feedback also benefits bridging the gaps in vocabulary transfer and satisfying affective needs. As a result, the deployment of all possible linguistic repertoires leads to a better meaning negotiation and acknowledges learner-centered language pedagogy.

Nevertheless, it remains inconclusive on the significance of implementing translanguaging in different types and modalities of feedback across diverse educational contexts. This literature review aims to elucidate the ways in which translanguaging in FL pedagogy was utilized as feedback resources and practices, foregrounding our current understanding of the contributions of translingual practices in the field of communicative foreign language (FL) teaching and learning.

To achieve this, a semi-systematic literature review (SSLR) was carried out. This paper first presents the methodology utilized in this literature review. Thereafter, relevant empirical studies published from 2017 to October 2022 are collected and then consolidated to scrutinize how “translanguaging” was deployed in hybrid dynamic discursive multimodal feedback across different educational contexts. Then, the facilitative roles of this interactive pattern are clarified, and the challenges are identified in association with unintended consequences of translanguaging on learners’ affective dimension and language learning in schooling. Finally, the study discusses the pedagogical implications of this emerging pattern for future communicative language education.

- Methodology

In this paper, a semi-systematic review approach is utilized to identify and comprehend the potential correlations between translanguaging implementation and interactive feedback in classroom contexts. The potential contribution of this review approach is highly valuable, as it assists in mapping novel theoretical perspectives and consolidating the existing knowledge about emerging topics, thereby providing a framework for future research (Snyder, 2019). Consequently, the review is guided by the following research questions:

(1) How do empirical studies on translanguaging differ in terms of their context (i.e., educational settings and languages) as well as their methodology?

(2) What are the characteristics of feedback which include translanguaging in FL writing tasks?

(3) How was translanguaging implemented to mediate corrective feedback provision?

The methodology of this study followed a multiphase review procedure that included: (a) search term selection, (b) data abstraction, and (c) data analysis. Firstly, a bibliographic search for articles in indexed journals was conducted on Scopus and Google Scholar, covering the last five years, from 2017 to 2022. In this step, search terms played a crucial role in ensuring a (semi-)systematic review to maximize the retrieval of relevant results and optimize the quality of the search strategy (Bramer et al., 2018). Hence, keywords were vital in defining the inclusion criteria and narrowing the search process towards translanguaging and feedback in L2 teaching and learning. Table 1 illustrates the search criteria and the keywords employed in this literature review.

| Table 1. Keywords used in this literature review. | |

| Search order | Keywords |

| 1 | “translanguaging” AND “feedback” OR “corrective feedback” |

| 2 | “translingual approach” AND “feedback” |

| 3 | “feedback” AND “translanguaging” OR “translingual practice” |

| 4 | “feedback” AND “pedagogical” AND “translanguaging” |

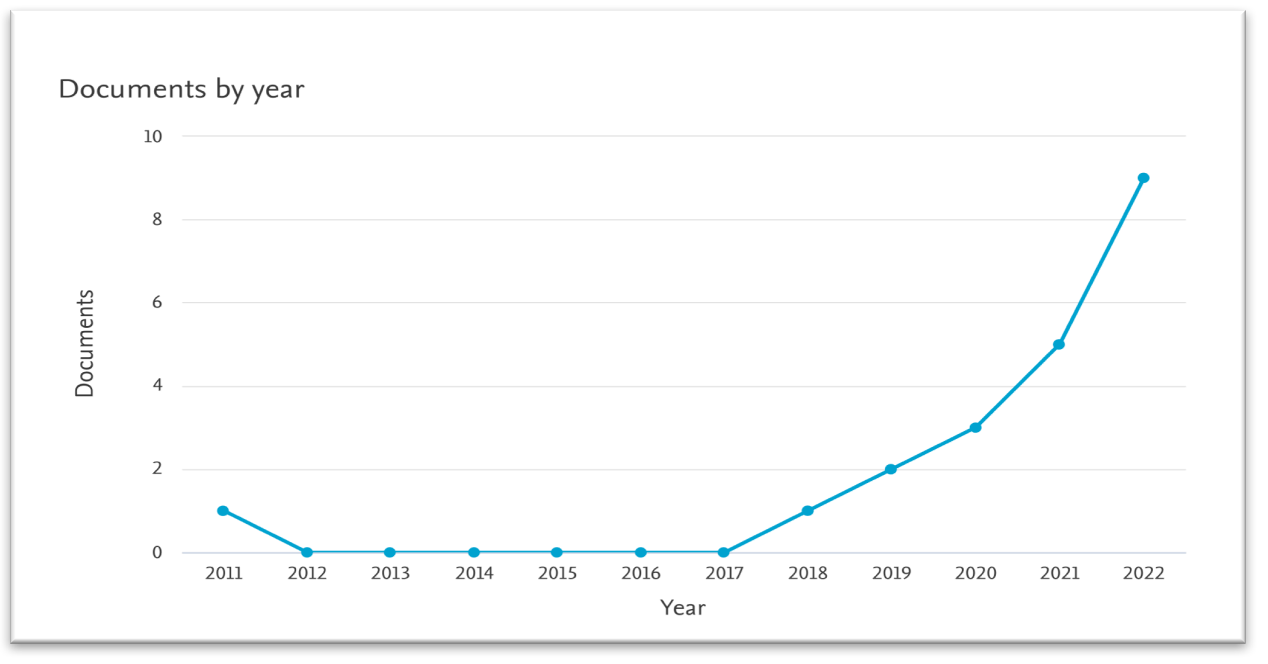

Initially, 10,600 research articles were identified, which necessitated a further systematic review of the titles, abstracts, and keywords referenced in the articles that specifically related to translanguaging and feedback provision in various classroom contexts. The systematic search encompassed all online citations available, starting from 2017 until October 2022, as the number of publications on translanguaging and feedback (e.g., CF) appears to have been noticeably increasing from 2017 onwards, as demonstrated in Figure 1:

|

Figure 1. Publications on translanguaging in corrective feedback provision by year ((https://www.scopus.com/home.uri, accessed on 1 February 2023). |

The full texts are screened to identify whether the papers draw on empirical data using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods for data collection. Consequently, the selection was based on the primary criteria for inclusion, as shown below:

- The document and source categories were “research article” and “Journal”; hence, reports, bibliographies, book reviews and conference proceedings had been removed;

- The language should be in English, Chinese, or Portuguese;

- The article presented findings based on empirical evidence, specifically excluding theoretical pieces and review studies;

- The article discussed a study that was conducted in foreign language education settings;

- The article described a study that focused on contextualized translanguaging practices within formal and multilingual educational settings. Specifically, the study included primary schools, high schools, universities, and academic institutions;

- The scope of articles was closely related to the concept of “translanguaging”, therefore, papers that deviated from the topic or discussed associated notions such as “code-switching,” “code-mixing,” “code-meshing,” “code-crossing,” and “plurilingualism” were excluded;

- The articles presented findings that informed the topic of pedagogical translanguaging and CF in particular;

- The article was peer-reviewed, and the full text was available.

Following these criteria, 22 articles were selected and obtained as a corpus for review processing.

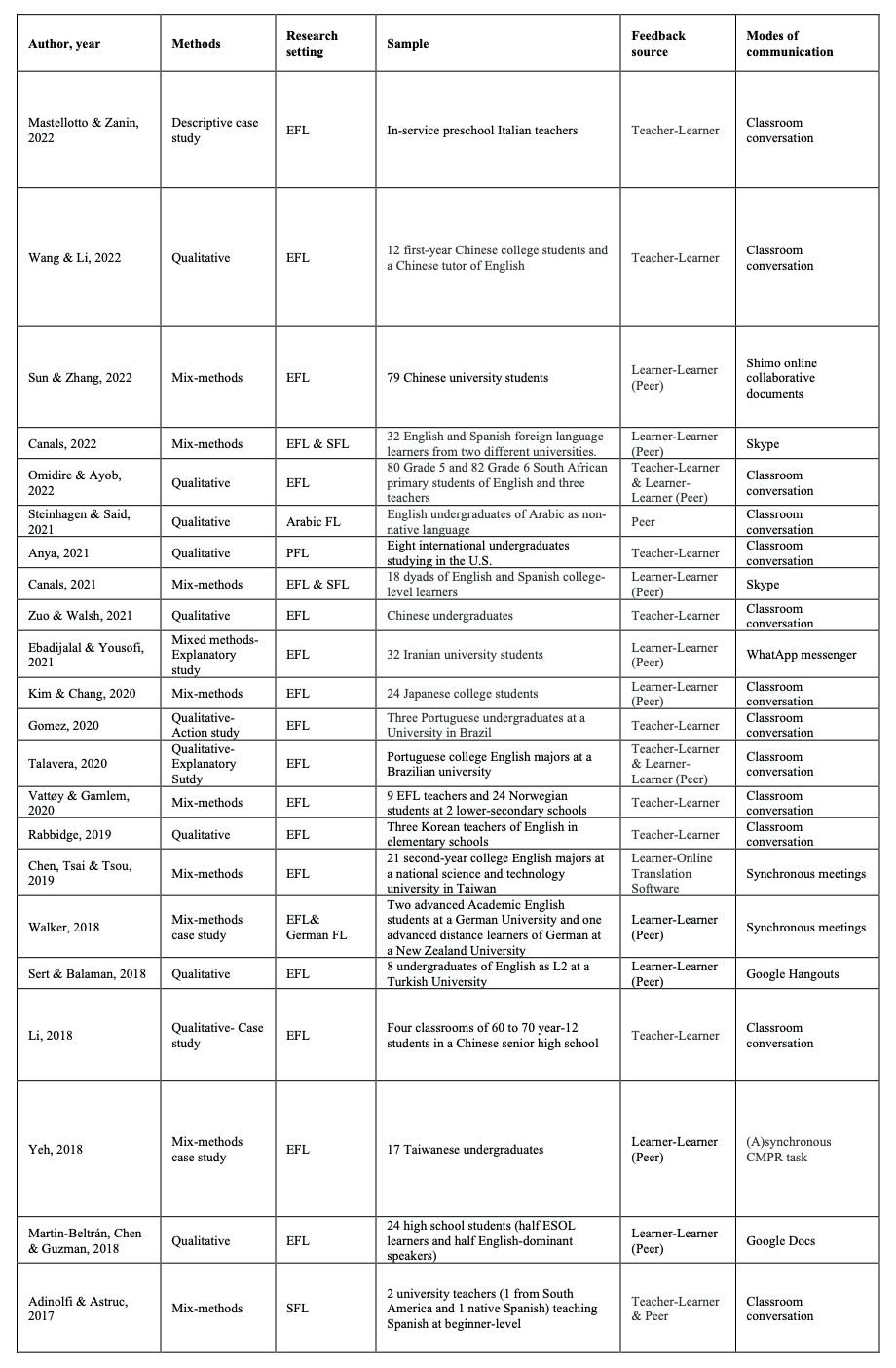

The subsequent step involves abstracting the relevant articles for qualitative data analysis. Table 2 outlines the 22 articles chosen as the data-driven source for this literature review, coded by the following categories:

- Authors and published years;

- Research methods;

- Research setting;

- Sample;

- Feedback source;

- Modes of communication.

This classification was elaborated after a brief revision of each paper, under the scope of the three aforementioned research questions.

Table 2. The synopses of selected empirical research articles.

- Results

I structure this section in accordance with the research questions.

- How do empirical studies on Translanguaging differ in terms of their context (i.e., educational settings and languages) as well as their methodology?

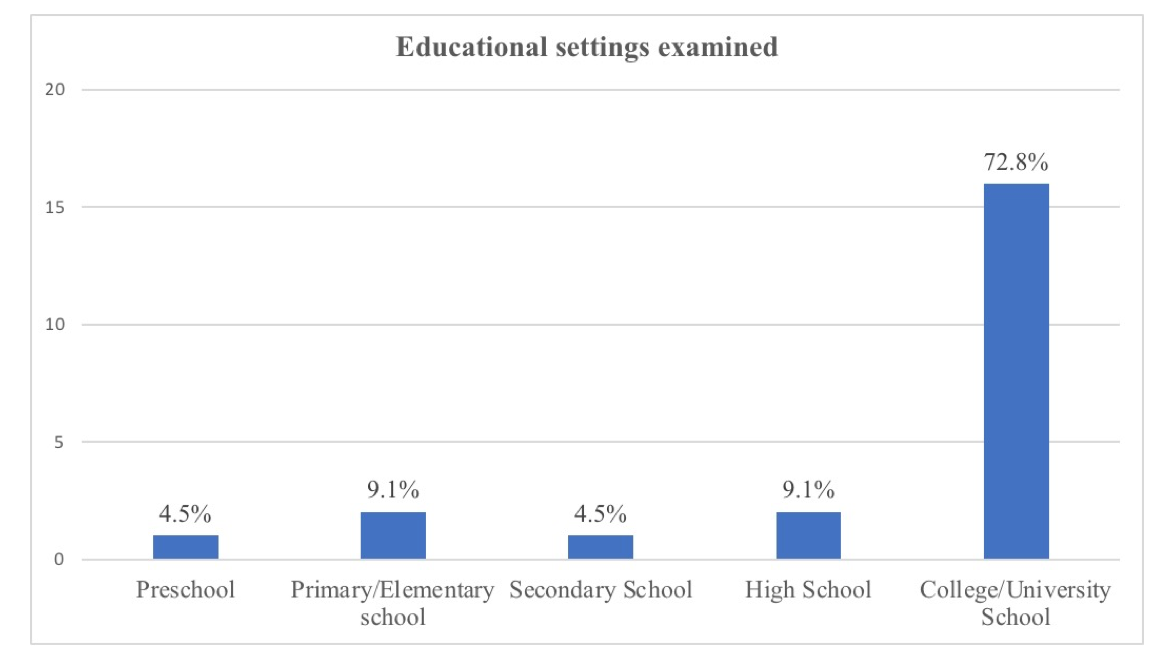

The selected articles were categorized based on the level of education they focused on, which included preschool, primary/elementary school, secondary school, high school, and college/university level. The raw frequencies and percentage frequency distribution of the levels of education are presented in Figure 2.

English was the dominant language in the corpus, both as a target language among all levels of education and as the learners’ FL and teachers’ L1 or L2. The second most prominent language was Spanish as the target language. Other languages used in the research settings of the corpus included Arabic, German, Portuguese, Italian, Afrikaans, Turkish, and others. In most cases, Chinese was the most dominant language as the learners’ L1.

Figure 2. Educational settings examined.

Figure 2. Educational settings examined.

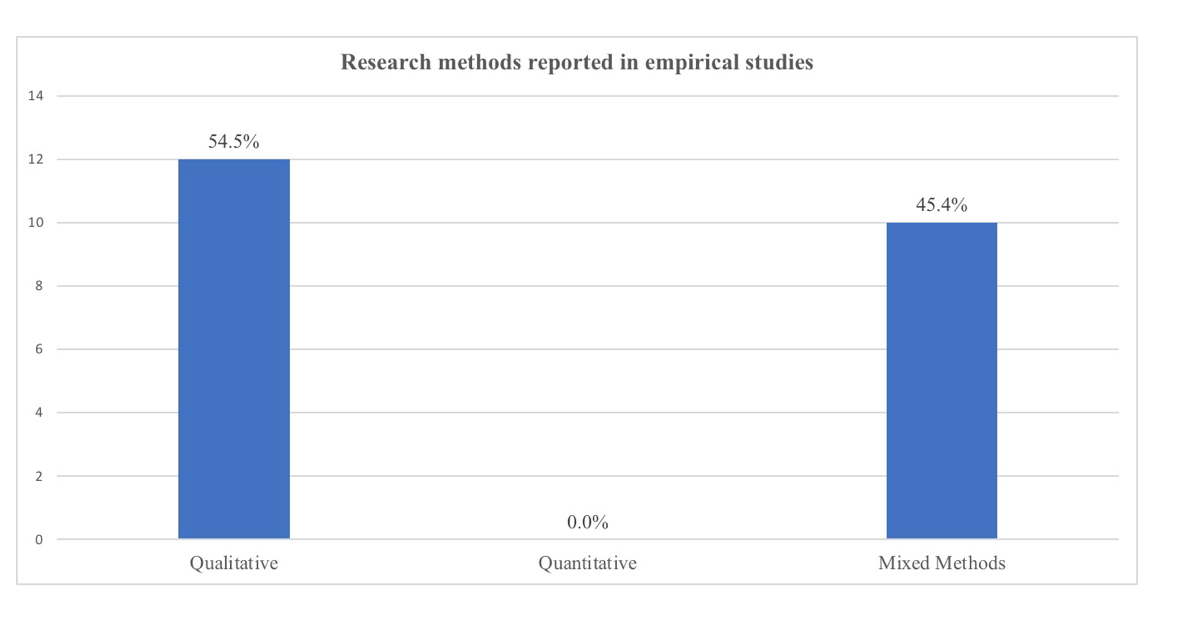

The remaining part of the first research question pertains to the research methods employed in each of the articles included in this review. In this category, the studies were first categorized based on their methodological approach, including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research. The analysis revealed that 54.5% (N=12) of the studies employed qualitative procedures in their methodological sections, 45.4% (N=10) were conducted using mixed methods, and there were no papers that reported quantitative-only methods. Further, when examining the qualitative studies, it was found that combined discourse and thematic analysis (e.g., Wang & Li, 2022; Omidire & Agbo, 2022; Gomez, 2020; Talavera, 2020; Sert & Balaman, 2018; Martin-Beltrán et al., 2018) and ethnographic microanalysis (e.g., Anya, 2021; Talavera, 2020; Li, 2018) were utilized in the majority of the qualitative studies. In the case of mixed methods studies, quantitative and qualitative data analysis were primarily used (e.g., Sun & Zhang, 2022; Canals, 2022, 2021; Ebadijalal & Yousofi, 2021; Kim & Chang, 2020; Chen et al., 2019; Walker, 2018). Figure 3 provides an overview of the methodology employed in this literature review. A half proportion of the empirical research was large-scale case studies that predominantly conducted qualitative or mixed methods (e.g., socio-cultural analysis, discourse and content analysis), exhibiting the way in which access to the tutor’s treatment of inadequate writing was incorporated, drawing on learners’ entire repertoires in a flexible and inclusive manner.

Figure 3. Overview of research methods reported in this literature review.

The study now proceeds to the next stage of the analysis to address the second research question.

- What are the characteristics of feedback which include translanguaging in FL writing tasks?

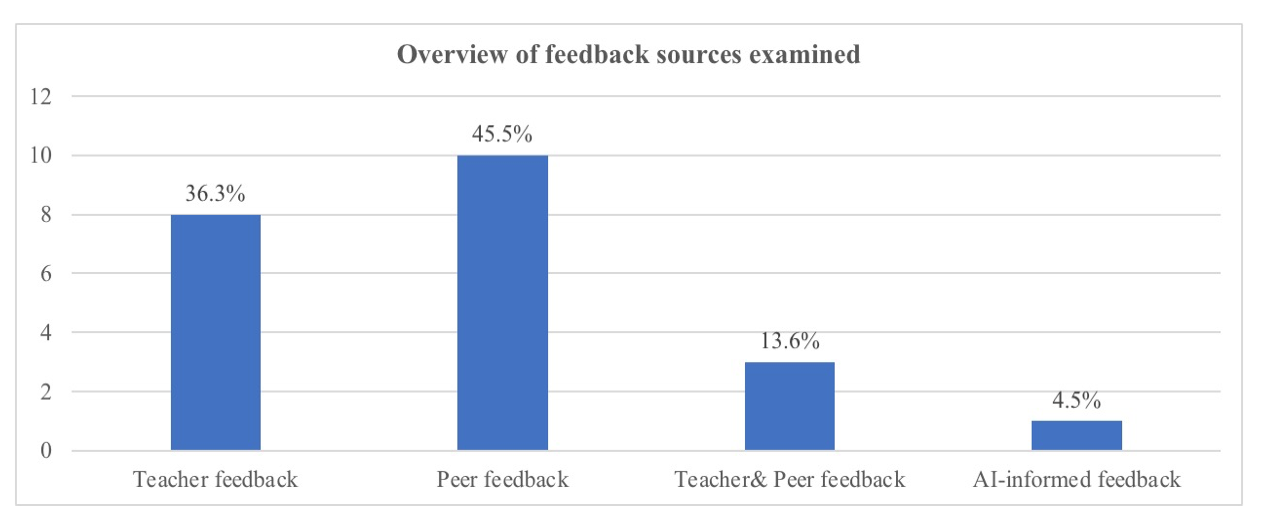

To address this question, the studies were first categorized based on who was involved in the CF provisions, thus four types were identified: teacher feedback, peer feedback, feedback in both conditions, and AI-informed feedback. The results, shown in Figure 4, revealed that peer feedback (N=10) and teacher feedback (N=8) were the main sources of communication in which translanguaging practices were meaningfully and constructively employed across various levels of classroom contexts. In addition, the context of feedback practices where translanguaging episodes were embedded was predominantly in on-site classrooms, although a few studies situated peer feedback via computer-mediated communication, e.g., online collaborative writing and blogging (Canals, 2022; Martin-Beltrán et al., 2018), video-based conferencing (Walker, 2018), mobile-based messengers (Ebadijalal & Yousofi, 2021), among others. Another finding related to the feedback modes showed that language practices were more frequently observed in multimodal communications than in monomodal interactions as a consequence of translanguaging-oriented interventions.

Figure 4. Overview of feedback sources examined in the corpus of studies.

Figure 4. Overview of feedback sources examined in the corpus of studies.

The remaining section of the second research question pertains to the feedback varieties expounded upon in the studies. According to the majority of the selected research, CF predominantly occured in the performance of tutor and peer responses, it is “information communicated to the learner that is intended to modify his or her thinking or behavior for the purpose of improving learning” (Shute, 2008: 154), and can take diverse forms and strategies in task-based language practices. For example, Mastellotto and Zanin (2022) categorized three critical feedback strategies in accordance with Nassaji and Kartchava (2021): guaranteeing children’s comprehension, promoting children’s output, and implicit CF. The study showed that translanguaging, as a collaborative, creative, and transformative space, can serve as a productive pedagogical metaphor for preschool children to achieve their communicative goal and meaning-making objectives (see Medina, 2022). Wang and Li (2022) adopted feedback classifications and features proposed by Lyster and Ranta (1997), and classified six types of CF to investigate the role of translanguaging in tutor oral responses: explicit correction, recast, clarification request, metalinguistic clues, elicitation, and repetition. Gomez (2020) identified the aspects regarding feedback values and described three feedback strategies that coexist in the act of translanguaging: providing guidance, meeting clear objectives set by the tutor, and constructing dialogic spaces.

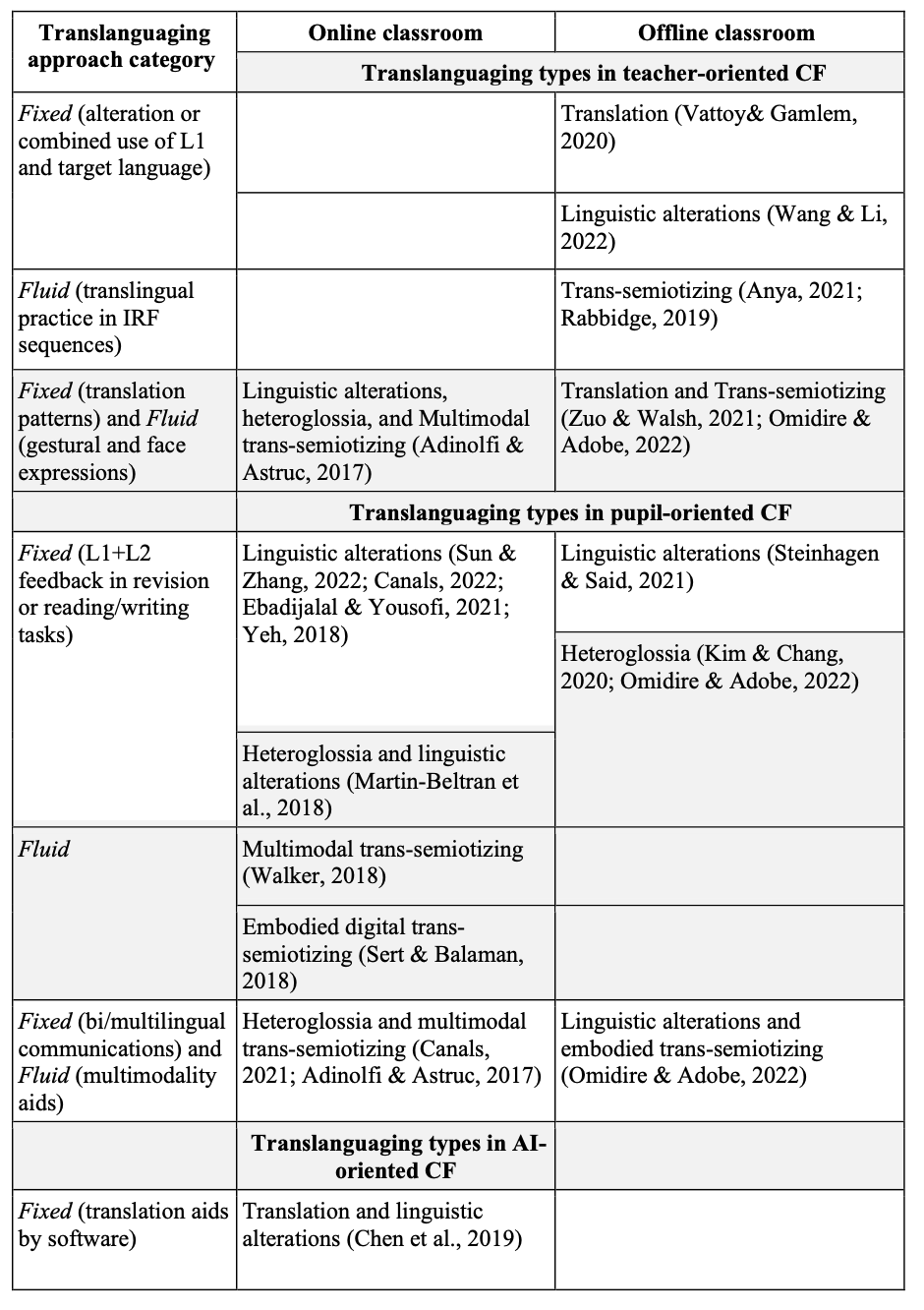

3.3 How was translanguaging implemented to mediate corrective feedback provision?

To address this question, an analysis was conducted on relevant information from various papers. To accomplish this review, the genealogy of translanguaging in language education, as traced by Bonacina-Pugh, Cabral, and Huang (2021: 16), was followed, utilizing the conceptual map of two study methodologies wherein the term was employed and developed: the ‘fixed language approach’ and the ‘fluid languaging approach.’ The former makes the reference to the “planned, systematic and functional use of two languages in the bilingual classroom,” while the latter regards translanguaging as the “fluid and dynamic use of a complex set of semiotic signs” (2021:7). For example, in the study of Steinhagen and Said (2021), separate languages were used by the teacher for specific teaching functions and were viewed as separate and bounded entities, this kind of “plurilingual heteroglossic pedagogy” (García & Flores, 2016) is considered within the domain of fixed language approach, in this situation, translanguaging has been evolved into a pedagogy that pertains to a planned alteration of separate languages (Cenoz & Gorter, 2017). On the contrary, in the study of Walker (2018), the complexity of digital, multimodal, and multilinguistic resource participation was unfolded through discursive peer online interactions, coming to signify the epistemological turn in today’s sociolinguistic realities where “the practice of making meaning using different semiotic signs as one integrated system” (Li, 2018b, cf. Bonacina-Pugh et al., 2021).

In the revision of these empirical articles, a content analysis was conducted on these 22 studies, examining them through the lens of translanguaging approaches, feedback mode and context, feedback interlocutors, and translanguaging types which were suggested by Sah and Kubota (2022). The findings of the content analysis were presented in Table 3, summarizing the way translanguaging was approached in language practices, particularly in CF-related episodes. In online classroom settings, several studies (Adinolfi & Astruc, 2017; Canals, 2021; Martin-Beltran et al., 2018) adopted a mixed translingual approach in providing CF, incorporating multimodality and digital tools in the revision of writing tasks. Some studies (Ebadijalal & Yousofi, 2021; Sun & Zhang, 2022; Canals, 2022; Chen et al., 2019) typically employed translanguaging in a fixed approach, focusing on the alteration or combination use of the target language and L1 in peer CF, contributing to the development of grammatical, lexical, and metalinguistic knowledge in achieving the meaning-making objective. In face-to-face classes, the fixed language approach was also identified as a prominent translingual strategy in tutorial CF, involved in biliteracy practices (Talavera, 2020), instructional error corrections (Wang & Li, 2022; Li, 2018), and interactional output (Mastellotto & Zanin, 2022; Gomez, 2020). It was inferred that communication is influenced by the similarity between form and meaning, based on in-class activity, teaching outcome, and cultural backgrounds during translingual practices when language choice is negotiated.

Table 3. The forms of translingual practices in corrective feedback (CF).

Translanguaging enabled learners and teachers to leverage various linguistic, semiotic, and translingual resources as an integrated system to complete international tasks, where CF plays a vital role in intrapersonal meaning exchanges (García and Li, 2014; Li, 2018; Sun & Zhang, 2022). By utilizing translanguaging in various forms of feedback, both social and linguistic practices can lead to a pedagogical shift from a monolingual to a translingual approach in L2 and FL teaching and learning (Canagarajah, 2018). In accordance with the counterbalance hypothesis proposed by Lyster and Mori (2006), feedback provisions in these selected empirical studies were categorized into two generic purpose-oriented groups: instructional CF and interactional CF. In the former, teacher-directed translingual practice (i.e., when translanguaging is planned by the teacher) occurred more frequently (e.g., Talavera, 2020; Steinhagen & Said, 2021), whereas in the latter, peer-directed translanguaging practice (when translanguaging is planned by peers) was predominantly employed in online collaborative writing tasks (e.g., Yeh, 2018). Although the fluid languaging approach was suggested in both types of CF to foster the multisensory and multimodal process of language learning and use (Albawrdi, 2018), many of these empirical pieces of evidence (e.g., Omidire & Adobe, 2022; Anya, 2021; Zuo & Walsh, 2021) demonstrated the necessity of combining fixed and fluid translingual approaches in FL education. This can not only assist learners in demonstrating their knowledge about a specific genre and transferring it to similar genres in different language codes, providing available lexico-grammatical resources (Medina, 2022), but also foreground teachers’ and students’ multilinguistic repertoires and multimodal practices, where new discourses and forms of expression were being produced.

- Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The objective of this literature review aimed to review the recent 5-year research on translanguaging pedagogies in teacher-learner and peer-peer feedback related to error treatment on FL learners’ written and oral production. To achieve this goal, a semi-systematic review was conducted to provide methodological and practical contributions, map theoretical approaches, and identify knowledge gaps within the literature (Snyder, 2019). Following the screening procedures, as described in detail in the methodology section, the analysis was focused on a corpus of 22 empirical studies that approached translanguaging in feedback-related language practices and met all the inclusion criteria set forth for this investigation to address its research questions.

The first research question sought to identify the characteristics of empirical studies on translanguaging regarding the educational context, target language, and research methods. The analysis showed that there was a significant proportion of studies conducted in English-related contexts, with English being the primary FL of learning. Moreover, translanguaging in CF was found to have been studied more frequently in tertiary educational contexts (see Figure 3). This could be attributed to the increasing inclusion of English as a common global second language in college-level language policy and planning, as well as the growing internationalization of education. In terms of methodology, a disproportionately large number of studies utilized qualitative and mixed-methods approaches, which is partially consistent with the findings of Prilutskaya (2021) and Medina (2022).

The following question delved into the feedback sources and types in which translanguaging was involved. Four categories were identified based on the participants initiation and response in oral and written interactions. It was found that translingual practices were explored more in peer feedback than teacher feedback, which suggests that L2 writing peer-as-provider feedback has demonstrated more variation in the translanguaging condition compared to tutorial corrective feedback (Sun & Zhang, 2022). In terms of feedback types examined in the 22 empirical research articles, CF was most frequently studied and regarded as the basis of translingual practice in classroom contexts. Wang and Li (2022) claimed that translanguaging can have a positive impact on FL learners’ writing, particularly in oral CF, as it enhances students’ learning and encourages their participation by providing them with a better understanding of grammatical or syntactical rules. However, some divergent empirical evidence suggests that translanguaging pedagogy is not always effective for the development of L2 performance. For example, Canals (2022) analyzed translanguaging sequences in language-related episodes (LREs) and found that translanguaging did not exerted a more facilitative role in explicit CF or produce modified output in learner-learner interactions. Talavera’s (2020) study highlighted pedagogical considerations related to this issue and suggested that translanguaging could be better approached in both teacher and peer CF so that learners can tap into all their linguistic resources when communicating with classmates, while their transferable skills between their native L1 and L2 can be improved under translingual teaching support and multimodal aids.

To address the final research question regarding the implementation of translanguaging in CF, a comprehensive analysis was conducted on studies that follow translanguaging approach and types categorized by Bonacina-Pugh et al. (2021) and Sah & Kubota (2022). Results revealed that in teacher-oriented CF, pedagogical translanguaging was frequently employed in both context-focused and form-focused negotiations, which are pedagogical strategies devised by the teacher within the physical or virtual classroom (Cenoz et al., 2022). Meanwhile, in pupil-oriented CF, spontaneous translanguaging was more commonly used in computer-mediated communication environments, which are discursive practices of multilingual speakers that occur both inside and outside school and are not planned by the teacher (ibid, 2022). A fixed language approach to translanguaging placed a high emphasis on communicative strategies such as linguistic alterations and heteroglossia with schooling and societal implications (Poza, 2017), that help reinforce vocabulary and grammar teaching (e.g., Talavera, 2020; Wang & Li, 2022; Li, 2018) and promote dialogic understanding and cognitive engagement (e.g., Gomez, 2020; Mastelloto & Zanin, 2022). A fluid languaging approach, on the other hand, placed a greater value on multiple forms of trans-semiotizing, such as embodied, digital, and multimodal trans-semiotizing, which were highly valued in some studies (e.g., Anya, 2021; Canals, 2021; Sert & Balaman, 2018) and used the entire linguistic and semiotic repertoire to fulfill peer communicative demands. Additionally, providing two or more types of translanguaging practices were shown to be productive methods in both approaches that teachers and learners used to exploit diverse linguistic resources and multimodal resources in resolving nonunderstandings (Sah, 2022). Therefore, rather than relying on a single type of translanguaging, the combination use of different translanguaging strategies should be implemented to create a critical space for scaffolding learning in FL classrooms and to enhance current knowledge of the target language.

Translingual mediation has been approached pedagogically into various forms of corrective feedback. Kim and Chang (2020) categorized CF and feedback commentary into ‘form’ (e.g., ‘grammar’, ‘expression’, and ‘mechanics’), ‘content’, ‘organization’, ‘comments with explanations’, ‘suggestions’, and ‘questions’ (2020: 5). Adinolfi and Astruc (2017) implemented translingual mediation in CF through five interactional patterns: ‘giving instructions’, ‘reviewing language’, ‘eliciting language’, ‘setting up dialogues’, and ‘prompting non-verbal responses’ (2017:194). Planned or spontaneous interlinguistic and trans-semiotic mediation in CF has been shown to be an effective strategy for the development of language users’ communicative and intercultural competencies (Cummins, 2019), whereas learners’ writing accuracy and lexical-grammatical knowledge in the target language could be better fostered, combined with the assistance of automated writing systems. On the one hand, the technological aids help students to be self-aware of micro-level written errors and to correct them effectively, on the other hand, it may help alleviate teachers of the time-intensive practice of CF provision. Therefore, in future research designs it is suggested that an automated CF could be provided at the early stage of learners’ FL writings as a task discussion clue for further translingual in feedback commentaries.

The present paper calls for a more holistic understanding of not only the writing product but also of L2 learners’ writing process. As such, it may be insightful that more research addresses how personalized and effective corrective feedback can be translanguaged by teachers, and how learners behave themselves in the writing process through feedback practices to optimize their learning strategies. For this, researchers are suggested to consider how context and participants would mediate or be mediated by the overall research ecology, and they could provide context-specific, individualized analysis of the impact of L2 writing feedback (Liu & Yu, 2022). Alongside discursive interactions between peers, tutorial translingual CF might help more to improve learners’ writing performance, to enable learners’ uptake, and to raise metalinguistic awareness in multilingual classrooms. Furthermore, in improving the quality of feedback, understanding the learners´ beliefs and goals is crucial for providing appropriate responses and reactions. Another recommendation based on this review study concerns teachers’ fundamental knowledge regarding their students’ linguistic repertoires, educational backgrounds, and language choices, before adopting specific CF strategies in writing instructions (Bitchener & Storch, 2016; Mu et al., 2023). Lastly, as a creative, transformational and collaborative space, where learners have different meaning-making goals and communicative purposes, the implementation of translanguaging in foreign language writing instruction should also be tailored to the learners’ needs and language proficiency (Hyland & Hyland, 2019), so that this pedagogical tool can foster reliable feedback to grasp students’ learning position and misunderstandings, thereby enhancing self-directed learning and self-awareness in academic settings.

In conclusion, this review has its limitations. Firstly, only two large and multidisciplinary databases were searched, which may have resulted in a reduced number of selected publications for the analysis section. Secondly, the review questions were mostly related to research methods, settings, feedback sources, and translanguaging approaches, with limited examination of the potential impact and contributions of translanguaging in CF practices. Furthermore, the five-year time scale of the review is insufficient to provide a historical perspective on the current state of knowledge on translanguaging and CF, which have been actively investigated for two decades. Future research should broaden the scope of the review to include all studies on translanguaging in CF practices. Notwithstanding possible limitations, the findings of this semi-systematic review of empirical studies are consistent with the literature on translanguaging and highlight the potential benefits of implementing translanguaging in CF practices in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms, where multiple languages and nonlinguistic resources are mastered for communication and meaning-making to promote pedagogical progress.

References

Adinolfi, L., & Astruc, L. (2017). An exploratory study of translanguaging practices in an online beginner-level foreign language classroom. Language Learning in Higher Education, 7(1).

Albawardi, A. (2018). Digital literacy practices of Saudi Female university students [PhD Thesis].

Anya, U. (2021). The taquito hot seat: Socializing monolingual bias through error correction practices in a Portuguese language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 54(3), 626–646.

Bitchener, J., & Ferris, D. R. (2012). Written Corrective Feedback in Second Language Acquisition and Writing. Routledge.

Bitchener, J., & Storch, N. (2016). Written Corrective Feedback for L2 Development. Multilingual Matters.

Bonacina-Pugh, F., da Costa Cabral, I., & Huang, J. (2021). Translanguaging in education. Language Teaching, 54(4), 439–471.

Bosma, E., Bakker, A., Zenger, L., & Blom, E. (2022). Supporting the development of the bilingual lexicon through translanguaging: a realist review integrating psycholinguistics with educational sciences. European Journal of Psychology of Education.

Bramer, W. M., De Jonge, G. B., Rethlefsen, M. L., Mast, F., & Kleijnen, J. (2018). A Systematic Approach to Searching: an Efficient and Complete Method to Develop Literature Searches. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(4).

Canagarajah, S. (2018). Translingual Practice as Spatial Repertoires: Expanding the Paradigm beyond Structuralist Orientations. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 31–54.

Canals, L. (2021). Multimodality and translanguaging in negotiation of meaning. Foreign Language Annals.

Canals, L. (2022). The role of the language of interaction and translanguaging on attention to interactional feedback in virtual exchanges. System, 102721.

Cenoz, J. (2017). Translanguaging in School Contexts: International Perspectives. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 193–198.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2022). Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge University Press.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Pedagogical translanguaging: An introduction. System, 10(3-4), 102269.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Minority languages and sustainable translanguaging: threat or opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(10), 901–912.

Cenoz, J., Santos, A., & Gorter, D. (2022). Pedagogical translanguaging and teachers’ perceptions of anxiety. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–12.

Chen, F., Tsai, S.-C., & Tsou, W. (2019). The Application of Translanguaging in an English for Specific Purposes Writing Course. English Teaching & Learning, 43(1), 65–83.

Cummins, J. (2019). The Emergence of Translanguaging Pedagogy: A Dialogue between Theory and Practice. Journal of Multilingual Education Research, 9(1), 19–35.

Ebadijalal, M., & Yousofi, N. (2021). The impact of mobile-assisted peer feedback on EFL learners’ speaking performance and anxiety: does language make a difference? The Language Learning Journal, 1–19.

Esquicha Medina, A. (2022). Translingüismo como una perspectiva que permite desarrollar literacidad académica en una lengua extranjera en educación superior: una revisión de literatura. Letras (Lima), 93(137), 86–101.

Fuster, C. (2022). Lexical Transfer in Pedagogical Translanguaging: exploring Intentionality in Multilingual Learners of Spanish (1st ed.). Stockholm University.

Galante, A. (2020). Translanguaging for Vocabulary Development: A Mixed Methods Study with International Students in a Canadian English for Academic Purposes Program. Educational Linguistics, 293–328.

García, O. (2009). Chapter 8 Education, Multilingualism and Translanguaging in the 21st Century. Social Justice through Multilingual Education, 140–158.

Garcia, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Gomez, M. N. (2020). The value of feedback in translanguaging: students’ insights from an English language course at Londrina State University.. Revista X, 15(1), 115.

Ha, X. V., & Murray, J. C. (2020). Corrective feedback: Beliefs and practices of Vietnamese primary EFL teachers. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 136216882093189.

Han, Z. H. (2002). Rethinking the Role of Corrective Feedback in Communicative Language Teaching. RELC Journal, 33(1), 1–34.

Hyland, K., & Hyland, F. (2019). Feedback in second language writing : contexts and issues. Cambridge University Press.

Kim, S., & Chang, C.-H. (2020). Japanese L2 learners’ translanguaging practice in written peer feedback. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(4), 1–14.

Leeman, J. (2007). Feedback in L2 learning: Responding to errors during practice. Practice in a Second Language: Perspectives from Applied Linguistics and Cognitive Psychology, 111–137.

Leung, C., & Valdes, G. (2019). Translanguaging and the Transdisciplinary Framework for Language Teaching and Learning in a Multilingual World. The Modern Language Journal, 103(2), 348–370.

Lewis, G., Jones, B., & Baker, C. (2012). Translanguaging: origins and development from school to street and beyond. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18(7), 641-654.

Li, J. (2018). L1 in the IRF cycle: a case study of Chinese EFL classrooms. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 3(1).

Li, S. (2010). The Effectiveness of Corrective Feedback in SLA: A Meta-Analysis. Language Learning, 60(2), 309–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00561.x

Li, W. (2011). Moment Analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235.

Li, W. (2018a). Translanguaging and Code-Switching: what’s the difference? | OUPblog. OUPblog. https://blog.oup.com/2018/05/translanguaging-code-switching-difference/

Li, W. (2018b). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30.

Li, W., & Ho, W. Y. (2018). Language Learning Sans Frontiers: A Translanguaging View. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 38, 33–59.

Liu, C., & Yu, S. (2022). Reconceptualizing the impact of feedback in second language writing: A multidimensional perspective. Assessing Writing, 53, 100630.

Lyster, R., & Mori, H. (2006). INTERACTIONAL FEEDBACK AND INSTRUCTIONAL COUNTERBALANCE. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(02).

Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). CORRECTIVE FEEDBACK AND LEARNER UPTAKE. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(1), 37–66.

Martin-Beltrán, M., Chen, P.-J., & Guzman, N. (2018). Negotiating peer feedback as a reciprocal learning tool for adolescent multilingual learners. Writing & Pedagogy, 10(1-2), 1–29.

Mastellotto, L., & Zanin, R. (2022). Multilingual teacher training in South Tyrol: strategies for effective linguistic input with young learners. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(4-5), 1–13.

Mu, S., Li, A., Shen, L., Han, L., & Wen, Z. (Edward). (2023). Linguistic Repertoires Embodied and Digitalized: A Computer-Vision-Aided Analysis of the Language Portraits by Multilingual Youth. Sustainability, 15(3), 2194.

Nagy, T. (2018). On Translanguaging and Its Role in Foreign Language Teaching. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica, 10(2), 41–53.

Nassaji, H. (2017). The Effectiveness of Extensive Versus Intensive Recasts for Learning L2 Grammar. The Modern Language Journal, 101(2), 353–368.

Nassaji, H., & Kartchava, E. (2020). Corrective Feedback and Good Language Teachers. Lessons from Good Language Teachers, 151–163.

Nassaji, H., & Kartchava, E. (2021). The Cambridge Handbook of Corrective Feedback in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Omidire, M. F., & Ayob, S. (2020). The utilisation of translanguaging for learning and teaching in multilingual primary classrooms. Multilingua, 0(0).

Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3).

Prada, J., & Turnbull, B. (2018). The role of translanguaging in the multilingual turn: Driving philosophical and conceptual renewal in language education. EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages, 5(2), 8–23.

Prilutskaya, M. (2021). Examining Pedagogical Translanguaging: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Languages, 6(4), 180.

Rabbidge, M. (2019). The Effects of Translanguaging on Participation in EFL Classrooms. The Journal of AsiaTEFL, 16(4), 1305–1322.

Sah, P. K. (2022). English medium instruction in South Asian’s multilingual schools: unpacking the dynamics of ideological orientations, policy/practices, and democratic questions. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 742–755.

Sah, P. K., & Kubota, R. (2022). Towards critical translanguaging: a review of literature on English as a medium of instruction in South Asia’s school education. Asian Englishes, 24(2), 132–146.

Sert, O., & Balaman, U. (2018). Orientations to negotiated language and task rules in online L2 interaction. ReCALL, 30(3), 355–374.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature Review as a Research methodology: an Overview and Guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104(104), 333–339. Science direct.

Steinhagen, T. G., & Said, F. (2021). “We should not bury our language by our hands”: Crafting creative translanguaging spaces in higher education in the UAE. In I. Papadopoulos & S. Papadopoulou (Eds.), Applied Linguistics Research and Good Practices for Multicultural and Multilingual Classrooms (pp. 169–183). novapublishers.

Sun, P., & Zhang, J. (2022). Effects of Translanguaging in Online Peer Feedback on Chinese University English-as-a-Foreign-Language Students’ Second Language Writing Performance. RELC Journal, 53(2).

Talavera, M. N. G. (2020). Supporting English language learning: pedagogical perspectives of translanguaging in English language teaching at higher education in Brazil [Doctoral thesis]. In bdtd.ibict.br. https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UEL_684480409fe4d83800f17ae31df14393

Talavera, M. N. G. (2017). Understanding translanguaging pratices as a pedagogical tool for language teaching. Salvador, 57, 38-57.

Vattøy, K.-D., & Gamlem, S. M. (2020). Teacher–student interactions and feedback in English as a foreign language classrooms. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(3), 1–19.

Walker, U. (2018). Translanguaging: Affordances for collaborative language learning. New Zealand Studies in Applied Linguistics, 24(1), 18–40.

Wang, Y., & Li, D. (2022). Translanguaging pedagogy in tutor’s oral corrective feedback on chinese EFL learners’ argumentative writing. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 7(1).

Yeh, C.-C. (2018). L1 versus L2 use in peer review of L2 writing in English. Asian EFL Journal, 20(9.1), 124–147.

Zuo, M., & Walsh, S. (2021). Translation in EFL teacher talk in Chinese universities: a translanguaging perspective. Classroom Discourse, 1–19.