Assessing metalinguistic awareness in multilingual classes

The ISSBM2022 Case Study

Greta Mazzaggio and Paolo Lorusso

University of Nova Gorica, Slovenia/University of Florence, Italy,

greta.mazzaggio@unifi.it

University of Udine, Italy,

paolo.lorusso@uniud.it

This paper explores the potential of multilingual practices in a multilingual classroom to facilitate the learning of linguistic theoretical tools and the development of metalinguistic thought. To teach linguistics to graduate students from diverse backgrounds, it is essential to provide a solid foundation of basic concepts, such as phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, to establish common ground (Caffarel & Martin, 2010). The class thus becomes a laboratory for a positive feedback loop, in which linguistic examples from different languages become social knowledge and identity recognition for each member of the class. Translanguaging, a technique for teaching a second language (Benes 2015), is a useful tool for metalinguistic assessment. In the present work, the role of multilingualism is described in how it was developed within the “International Summer School on Bilingualism and Multilingualism” (ISSBM 2022) which we organized in 2022 and that gave as a result the contributions collected in this book. Multilingualism played a crucial role in strengthening students’ ability to refer to metalinguistic concepts and to deal with them in a scientifically valuable way.

Keywords: translanguaging, education, second language, language acquisition, bilingualism

- Introduction: Metalinguistic awareness and where to find it.

Metalinguistic awareness refers to the ability to reflect upon and manipulate language as an entity to study and it is an essential concept in the study of linguistics. Precisely, it refers to the ability to reflect on and analyze language as an object of study, separate from its use in communication. In other words, it is the ability to think about language, talk about language, and understand language as a system of rules and structures (Tunmer & Herriman, 1984). In multilingual classrooms, students are often exposed to multiple languages and may be required to use them to varying degrees. Such immersion presents an opportunity for students to develop their metalinguistic awareness, as they must navigate the differences and similarities between languages (for deeper insights see, a.o., Roehr-Brackin, 2018). Despite the similarity in meanings between metalinguistic awareness and metalanguage, it is crucial to differentiate between the two. Metalanguage pertains to the language used for describing language, incorporating terms such as phoneme, word, or phrase. Metalinguistic awareness refers to an awareness of the usage of these terms rather than a mere acquaintance with the terms themselves. Consequently, to be metalinguistically aware “is to know how to approach and solve certain types of problems which themselves demand certain cognitive and linguistic skills” (Malakoff, 1992: 518).

In this respect, it is fundamental to define and differentiate between four concepts that are relevant as linked with metalinguistic awareness: tacit knowledge, linguistic competence, linguistic intuitions, and explicit formulation (Tunmer & Herriman, 1984). With tacit knowledge, we refer to the kind of knowledge that is not easily expressible in words or shared with others. In the context of metalinguistic awareness, tacit knowledge pertains to a person’s intuitive understanding of language, which may not necessarily be expressed or explained explicitly. Linguistic competence refers to a person’s ability to use language effectively and appropriately in diverse situations. This ability encompasses knowledge of various aspects of language, including grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and more. In other words, linguistic competence relates to a person’s knowledge of the rules and principles of language, which they use naturally and spontaneously. Linguistic intuitions denote a person’s innate sense of what is linguistically appropriate or inappropriate. This intuitive sense allows individuals to differentiate between different grammatical structures and identify ambiguous or ungrammatical sentences. Linguistic intuitions may be used to recognize instances where language use violates intuitively known rules. Finally, explicit formulation pertains to the ability to express and articulate language knowledge explicitly. In the context of metalinguistic awareness, explicit formulation relates to a person’s ability to describe and explain the rules and principles of language, which they use intuitively. It also encompasses a person’s ability to analyze their own language use more reflectively and analytically. In summary, while these concepts are all related to metalinguistic awareness, they refer to distinct aspects of language knowledge and use, including intuitive understanding, competency, intuitive sense, and explicit articulation.

There are several ways in which students can develop metalinguistic awareness. One example is by comparing and contrasting different languages. For example, students may notice that certain words in one language have no direct translation in another language. Moreover, students can evaluate the patterns of language usage across diverse situations and acquire insight into how language influences and is formed by social relationships and power dynamics by evaluating how language is employed in various settings, such as academic or social scenarios.

Another way in which students can develop metalinguistic awareness is by analyzing the structure and grammar of different languages. For instance, students may learn that certain grammatical rules that apply in one language do not apply in another language. This can help students understand the rules and patterns of language and can improve their overall proficiency in each language they are learning. Additionally, the study of linguistic variety, such as regional dialects, sociolects, and registers, can led to the analysis of social and cultural elements that impact language usage and develop a deeper understanding for the diversity of human communication by analyzing how language use differs across different social and cultural groups.

Ultimately, developing metalinguistic awareness entails not only comparing and contrasting different languages, but also assessing language usage across contexts, investigating it in various kinds of media, such as literature, cinema, and social media. In this way, students may obtain a greater grasp of how language is used to create and shape social reality by exploring how language is utilized to transmit meaning and shape viewpoints in these various mediums.

As an ultimate end, metalinguistic awareness can help students become more flexible and adaptable in their language use and this will cascade onto other cognitive and linguistic skills, as demonstrated by several experimental works (a.o., Bialystok, 1988; Bloor, 1986; de Haro et al., 2012; El Euch, & Huot, 2015; MacGregor & Price, 1999; Wenling et al., 2002). Students who are aware of the differences and similarities between languages can more easily switch between them and may be able to use their knowledge of one language to aid in their comprehension and use of another language (a.o., Koda, K., 2005; Talalakina, 2015; Woll, 2018). By fostering metalinguistic awareness, educators can help students develop a greater appreciation for the diverse ways in which humans communicate and can prepare them to be successful and adaptable language users in a globalized world.

In the field of linguistics, metalinguistic awareness is critical because it allows researchers and scholars to study language systematically and objectively. It enables them to identify patterns and structures within language, understand how language functions in different contexts, and develop theories about how language is acquired and used. This paper is meant to describe some general issues on metalinguistic didactics starting with some key notions of linguistic didactics. To achieve this goal, in section 2 we introduce some basic concepts on the didactics of language through the description of the didactic triangle, and in section 3 we will stress the role of interactivity in linguistic class. In section 4, we will introduce the role of translanguaging in teaching foreign languages in a multilingual environment and how it is meant to be useful also in the teaching of linguistics. Section 5 is then devoted to describing the linguistic classes as a laboratory for the acquisition of advanced metalinguistic skills. In sections 6 and 7 we will describe the characteristic of the “International Summer School on Bilingualism and Multilingualism” held in Chemnitz as a case study and we will propose some concluding remarks on the role of multilingualism in linguistic teaching.

- The didactic triangle

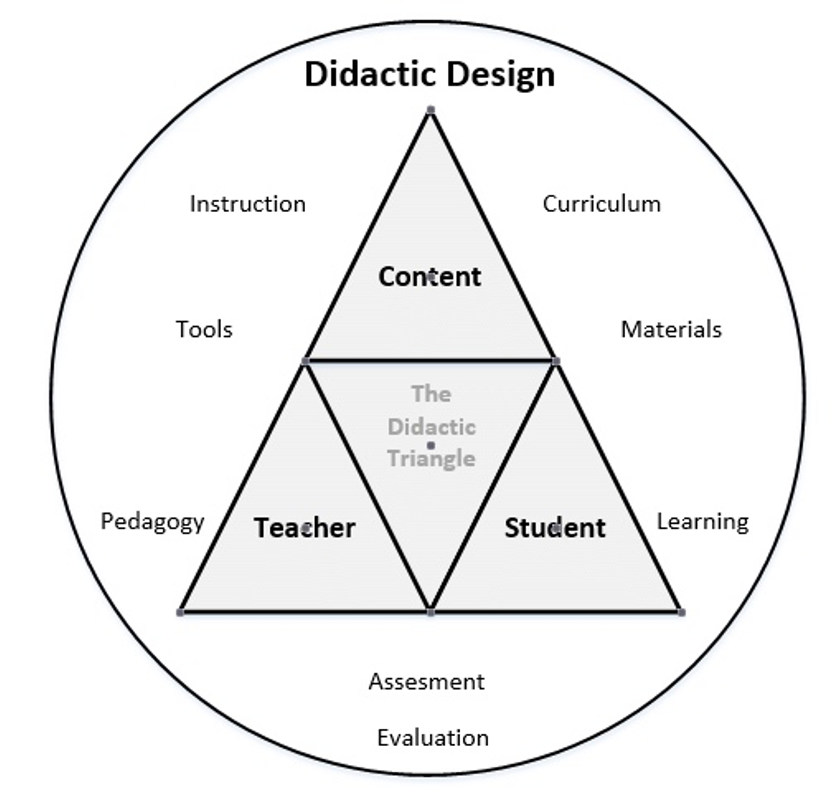

The didactic triangle is a widely used model in language education that depicts the interdependent relationship among the didactics’ three pillars: the teacher, the learner, and the content Figure 1). The success of language education relies on the effective interaction among these three elements (Künzli, 2000). A communication interaction exists between the teacher and the student. The teacher-subject relationship includes the teacher’s method of delivering the topic. The subject-student connection involves how and in what manner the student assimilates the knowledge, or which teaching approaches are given or suit the scenario (Augustsson & Boström, 2016: 3-4). It is quite clear how the teacher plays a crucial role in creating a conducive learning environment, facilitating learning, and guiding learners toward their language goals. Thus, the teacher needs to possess a strong comprehension of the language, the learners’ needs, and the most suitable teaching methods and materials to employ in the classroom.

Figure 1. The didactic triangle, Smith 2012

Let us examine the three pillars of the didactic triangle in greater detail. The role of the teacher in the didactic triangle is critical. The teacher must possess a comprehensive understanding of the language and the cultural context in which it is used. Additionally, the teacher should be well-informed about the learners’ needs and abilities and should be knowledgeable about the appropriate teaching methods and materials to use. The teacher must strive to create a supportive and stimulating learning environment that encourages the learners to be autonomous and engaged. In language teaching, the learners are the primary focus, and their needs and abilities should be taken into account when planning and delivering instruction. The learners must be actively involved in the learning process and motivated to take responsibility for their own learning. The teacher should provide ample opportunities for learners to practice using the language in authentic situations and provide constructive feedback and support as needed. The content of language teaching is the language itself and the cultural context in which it is used. The content must be relevant, meaningful, and engaging to the learners. The teacher should present the content in a way that is accessible and interesting, utilizing various teaching materials and techniques to enhance learners’ understanding and acquisition of the language (Augustsson & Boström, 2012; 2016; Richards & Rodgers, 2014).

The didactic triangle emphasizes the importance of a dynamic and interactive learning environment (see section 3). It encourages teachers to focus on learners’ needs and abilities and to design instruction that is relevant, meaningful, and interesting. It also highlights the importance of the cultural context in which the language is used and encourages teachers to incorporate cultural elements into their teaching. Overall, the didactic triangle is an essential model for language teachers, and it provides a useful framework for designing effective language instruction. By focusing on the interaction among the teacher, the learners, and the content, teachers can create a supportive and stimulating learning environment that promotes language acquisition and fosters learner autonomy and engagement. The next section is devoted to describing the role of interactivity in teaching linguistics.

- Interactivity

Interactivity is an essential aspect of teaching language and linguistics because it allows students to engage with the subject matter in a more meaningful way (Gass, 2017; Long, 1996; McDonough, 2004; Richard-Amato, 1988). Interactive teaching methods can help students better understand complex linguistic concepts, develop critical thinking skills, and apply what they learn in real-world situations (a.o., Omar et al., 2020; Pradono et al., 2013). The major ways to incorporate interactivity are the following:

- One way to incorporate interactivity in teaching linguistics is through classroom discussions. By encouraging students to share their thoughts and ideas, also in their first language (Tran, 2018; Turnbull, 2015), teachers can create a collaborative learning environment that fosters critical thinking and problem-solving. Classroom discussions can also help students develop communication skills and learn to express their ideas clearly and effectively.

- Another way to incorporate interactivity in teaching linguistics is through group activities and projects (Dobao, 2012; McDonough, 2004). By working together in teams, students can develop teamwork and collaboration skills while also applying what they have learned in a practical context. For example, students might conduct research on a particular language or dialect, create language-learning resources for the classroom, or analyze a corpus of written or spoken language.

- Interactive technology tools can also be useful in teaching linguistics (González-Lloret, 2019). For example, language learning software and apps can help students practice and reinforce their language skills in a fun and engaging way. Other technology tools, such as online language resources and interactive whiteboards, can help teachers present linguistic concepts in a dynamic and interactive way. Recently, also gamification has been considered to be one of the most enjoyable and effective methods (Dehghanzadeh et al., 2021).

- Finally, role-playing activities – also in their digital version – can be an effective way to teach language pragmatics and sociolinguistics (Cornillie et al., 2012; Livingstone, 1983). By simulating real-world communication scenarios, students can develop their understanding of how language is used in social contexts and learn to communicate effectively in different situations.

The interactivity model of language learning can have significant benefits for students, as it provides opportunities for students to engage with the material in a more active and participatory way. By engaging with the material through interactive activities, students can develop a deeper understanding of the language and its structure, which can improve their overall proficiency.

When language learning is based on interactive activities, it can offer several cognitive benefits. For one, interactive activities can increase engagement and motivation in language learners (Omar et al., 2020); this is because interactive activities allow learners to use their language skills in relevant and meaningful contexts, which can make learning more interesting and engaging. Interactive activities can also enhance memory retention (Lai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022), as learners are required to actively engage with the material and apply their knowledge in new contexts. By using their language skills in practical ways, learners are more likely to remember the material they have learned. Another benefit of interactive language learning is the potential for improved critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Liang & Fung, 2021). Indeed, interactive activities often require learners to analyze and synthesize information to complete tasks and solve problems. Finally, interactive language learning can also enhance language processing and production abilities (Omar et al., 2020). This is because interactive activities require learners to process and understand language in real-time interactions. Through practice and exposure, learners can improve their ability to understand and become more confident in their use of the language.

Overall, the interactivity model of language learning can have significant cognitive benefits for students and can help to improve their overall proficiency and confidence in the language. In conclusion, interactivity is an essential aspect of teaching linguistics. By incorporating interactive teaching methods, teachers can create a more engaging and effective learning experience for their students, help them better understand complex linguistic concepts, develop critical thinking skills, and apply what they learn in real-world situations. A part of interactivity, another aspect seems to have become crucial in language teaching which we think to be crucial also for the learning of linguistics: translanguaging. The next section is devoted to describing the main implication of translanguaging in language and linguistic teaching.

- Introducing multilingualism: Translanguaging

Translanguaging is a term used in sociolinguistics and language education to describe the phenomenon of multilingual individuals using their full linguistic repertoire to communicate and make meaning (García & Lin, 2017). Rather than seeing languages as separate and distinct entities, translanguaging emphasizes the fluidity and interconnectedness of languages and encourages individuals to draw on their entire linguistic repertoire, regardless of the language or context (Blackledge & Creese, 2010; Cenoz & Gorter, 2015, 2020; García & Li Wei, 2014).

The term ‘translanguaging’ was originally coined in Wales (Backer, 2001; Beres, 2015) to describe a kind of bilingual education in which students receive information in one language, for example, English, and produce an output of their learning in their second language, for example, Welsh. Since then, scholars across the globe have developed this concept and it is now argued it is the best way to educate bilingual children in the 21st century.

Fisher et al. (2018) describe the role of translanguaging in bilingual classes. In the 20th century, bilingual classrooms typically had strict language arrangements, dictating when and who should speak which language to whom. This practice was based on diglossic arrangements and models of bilingualism, which viewed languages as separate and distinct entities. However, in the 21st century, a heteroglossic conceptualization of bilingualism has become necessary, one that acknowledges the complex discursive practices of multilingual students, now more numerous, including their translanguaging abilities.

Translanguaging refers to the process of using multiple languages in the service of meaning-making, recognizing that languages are not separate and distinct, but rather interconnected and fluid. In a plurilingual classroom, students draw on their linguistic resources to construct meaning and negotiate communication and translanguaging allows students to use their entire linguistic repertoire to communicate and learn, rather than being restricted to one language or the other. Importantly, this is not only something that bilingual people do when they feel like they don’t have the words or phrases they need to communicate in a monolingual setting. The trans- prefix conveys how multilingual individuals’ language practices “go beyond” the usage of officially recognized designated language systems (García & Li Wei, 2014: 42; Vogel & García, 2017).

Translanguaging in education represents a shift away from the traditional model of bilingual education, which separates languages and restricts their use. Instead, it recognizes that students’ linguistic repertoires are complex and dynamic and that effective communication and learning require the use of all available resources. Translanguaging can be a powerful tool for promoting language learning in linguistics classes, especially for students from diverse linguistic backgrounds (Vogel & García, 2017). To achieve this, teachers should embrace and leverage their students’ multilingualism, encouraging them to use their full linguistic repertoire to engage with course material. This can involve using translanguaging strategies such as code-switching, translation, and interlingual mediation to model multilingual communication. Teachers can also enrich the linguistic examples used in class by drawing from a range of languages, helping students to see how linguistic concepts manifest in different linguistic contexts and encouraging them to draw on their own linguistic knowledge. Finally, creating a collaborative learning environment that emphasizes the importance of peer learning can foster inclusivity and engagement for all students.

The practice of translanguaging has been recognized both in classrooms that cater to immigrant and refugee students and in traditional language classrooms that offer instruction to students seeking to learn additional languages (Vogel & García, 2017). The case of the International High Schools (IHS), a network of public schools in the United States for newcomer immigrants, illustrates how translanguaging can be used to support dynamic plurilingual practices in instruction. The IHS network was founded in 1985 by the Internationals Network for Public Schools, a non-profit organization based in New York City. Students at IHS come from a variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds and may speak different languages, including Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin, and many others. The schools are built on seven principles that promote: heterogeneity, collaboration, learner-centeredness, language and content integration, language use from students up, experiential learning, and local autonomy and responsibility. By using these principles, the schools create a learning environment that values and supports students’ plurilingual abilities (García & Sylvan, 2011). Rather than restricting students to a single language, teachers and students collaborate to use all available linguistic resources to construct meaning and communicate effectively.

“The IHS “mantra” is that “every teacher is a teacher of language and content.” Language means both the additional language they are acquiring (English, as all students are emergent bilinguals who are learning English), as well as their home language (which students use to support the learning of both academic content as well as English)” (García & Sylvan, 2011: 396). For example, teachers may use students’ native languages to supplement their learning of English and academic subjects, using multilingual resources (e.g., bilingual dictionaries) or having students work collaboratively in mixed-language groups (see García & Sylvan, 2011 for more detailed examples). Moreover, students’ linguistic backgrounds are recognized as an important part of their identity and are used to investigate academic subjects from various angles. In a social studies class, for example, a teacher might encourage students to share their knowledge and perspectives on a historical event in their home countries, resulting in a more rich and diverse understanding of the topic. As a result, students become more knowledgeable and academically successful, as well as more confident users of academic English and more proficient in translanguaging.

In conclusion, the strict language arrangements commonly used in bilingual classrooms are no longer adequate for the complex and dynamic multilingual classrooms of the 21st century. Translanguaging offers a more inclusive and effective approach, one that values and supports students’ plurilingual abilities. By using translanguaging practices in instruction, educators can help students become more knowledgeable and academically successful, as well as more confident and proficient in using multiple languages in the service of meaning-making. As for metalinguistic meaning, translanguaging seems the perfect tool to be introduced in a multilingual linguistic class. The next section is devoted to focusing on the role of the multilingual class as a laboratory of linguistic acquisition.

- The multilingual class as a ‘laboratory’.

Overall, the laboratory of the class can be a valuable tool in teaching linguistics. A laboratory can be used to reinforce theoretical concepts and provide students with a hands-on experience that deepens their understanding of linguistics. Students can engage in various activities that facilitate their learning of language. For example, students can analyze language samples, conduct and see the results of experiments, and especially engage in problem-solving activities. These activities can help students better understand the principles of language and develop practical skills for analyzing and using language.

One benefit of using a linguistic class as a laboratory is that it can provide a more interactive and engaging learning experience. Rather than just reading about linguistic concepts, students can actively participate in activities that help them see how these concepts work in practice. This can make learning more fun and help students retain the information better.

Another benefit of using a linguistic laboratory is that it can provide a space for students to practice and refine their language skills together with the metalinguistic skills required to analyze it. For example, students can practice speaking, writing, and listening in the target second language they are learning. Nonetheless, their practice in a second language will also be the source of their metalinguistic reasoning.

The multilingual background of the student has a central role in this laboratory. A multilingual class can indeed serve as a laboratory of skill and linguistic competence. When students from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds come together in a classroom, they have the opportunity to learn from each other and develop their language skills in a collaborative and supportive environment. The social effectiveness of the multilingual laboratory relies on English (or any other language chosen as lingua franca) as the ‘metalinguistic language,’ and on the other languages which are either the object of the study or the identity competence of each student. A positive loop is created: 1) students will be given a social/scientific role within the class as speaker/data owner; 2) have an effect of a ‘virtuous circle’ since the examples of any language become both the shared knowledge and a field for the application of the theoretical part.

The main phases of the virtuous loop are:

1) Exposure to different language data: students in a multilingual class have the opportunity to be exposed to different languages and cultures. They can learn new vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation from their peers, which can help them develop their language skills and improve their metalinguistic abilities.

2) Practice speaking: a multilingual class can provide a safe and supportive environment for students to practice speaking in a new language (although for metalinguistic purposes). They can practice their pronunciation, intonation, and grammar with their classmates, which can help them build confidence and improve their speaking skills

3) Peer teaching: students in a multilingual class can also learn from each other through peer teaching. When a student teaches their classmates a new word or phrase in their native language, they not only help their peers learn, but they also reinforce their own knowledge and understanding of the language.

4) Increased cultural awareness: a multilingual class can help students develop an appreciation and understanding of different cultures. They can learn about different traditions, beliefs, and customs from their classmates, which can broaden their horizons and help them become more culturally competent.

To conclude, to improve linguistic and metalinguistic skills multilingualism and translanguaging strengthen the role of class as a social and scientific laboratory. In the next section, we describe the successful experience of the ISSBM 2022 in which we gave a central role to multilingualism and translanguaging.

- The “International Summer School on Bilingualism and Multilingualism” (ISSBM 2022) as a case study

The International Summer School on Bilingualism and Multilingualism (ISSBM) 2022 is a summer school that took place in Chemnitz, Germany, from September 12th to 16th, 2022.[1] The summer school was made possible through a grant that the authors of this paper received after applying for a call promoted by The European Cross-Border University (ACROSS) and the German Academic Exchange Service / Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). ACROSS is a consortium of ten universities from nine countries that represent the diversity of Europe. The universities that are part of ACROSS are located in four cross-border regions, including the two European Capitals of Culture 2025 (i.e., Chemnitz and Gorizia/Nova Gorica). This distinctive combination of expertise has enabled them to devise effective solutions to address the difficulties that arise in cross-border situations, thereby generating a powerful synergy that benefits higher education, the business community, and society as a whole. Two universities from this consortium, the University of Nova Gorica, Slovenia, and the University of Udine, Italy, through two of their members (i.e., the authors of this contribution), participated in the call and obtained funding for the organization of this summer school. During the summer school, a member of a third university in the consortium (Rezekne Academy of Technologies, Latvia) also participated as a lecturer.

6.1 Some data

ISSBM 2022 received a significant number of applications. Thanks to the financing, 15 students were awarded scholarships, providing them with the opportunity to attend the school, visit Chemnitz, and meet colleagues and professors from different backgrounds. The school had a total of 36 students from 23 countries (Germany, Italy, India, UK, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Alger, Bulgaria, Croatia, Turkey, USA, Tunisia, China, Finland, Iran, Poland, Brazil, Nepal, Switzerland, Slovenia, Spain, Ukraine and Romania), of which 16 attended in-person, and 7 instructors. All students actively participated in the school, asking questions and interacting with professors inside and outside of classes. The program included classes on various linguistic subfields, such as semantics, pragmatics, syntax, sociolinguistics, and prosody. The in-person students also had the opportunity to attend a guided tour of Chemnitz on the first day of the school to get to know each other. Online students were also offered an interactive guided tour in the form of an online game with final prizes. During a research session, some students presented their research and received useful feedback from their colleagues. At the end of the school, students asked for their classmates’ names and contacts so that they could stay in touch and collaborate. The organizers agreed to create a folder in which they could exchange materials and communications.

At the end of the experience, we asked students for feedback. In-person students expressed their positive evaluation of the school, highlighting the opportunity to meet experts in their respective fields and to engage in productive discussions with colleagues who share the same interests. They also appreciated the sense of community that was fostered. Online students also enjoyed the school, commenting on the high quality of the seminars and the opportunity to connect with other researchers from around the world. They also appreciated the inclusive approach of the organizers towards online participants.

6.2 The present volume

Following the summer school experience, students had the opportunity to collaborate with a paper to an Open Access book of proceedings, edited by the organizers of the event. The present paper is an introduction to the book.

The book contains a preface from Ariane Korn, the DAAD project coordinator, and eleven chapters written by students. The chapters covered a variety of topics linked to sociolinguistics, bilingualism, multilingualism and languages in contact. Let’s have a brief panoramic of what has been produced by students:

- Muhammed Sagir Abdullahi, from Nigeria, writes about code-switching in English language classes in tertiary institutions in Kano. Ethnography and Discourse Analysis are used as the methodology and theoretical framework, respectively. The findings show that teachers’ code-switching serves instructional and social functions, and the types of code-switching used were inter-sentential, intra-sentential, and tag-switching at different linguistic levels.

- Abdukkadir Abdulrahim, from Turkey, discusses the significance of corpus linguistics and corpus-based studies in foreign language teaching and learning. The lack of empirical studies exploring the actual impact of corpus methods on learning outcomes is highlighted, despite a significant number of publications on the topic. The study emphasizes the importance of adopting corpora in EFL (English as a Foreign Language) classrooms to enhance language learning environments and provide opportunities for teachers and students to become acquainted with the foreign language.

- Paweł Andrejczuk, from Spain, explores telecollaboration (TC) as a language learning approach that has gained interest due to recent global events, such as emergency remote teaching. The study adopts a meta-analytical approach to provide a synthesis of 38 journal articles published between 2016 and 2021, related to English as a lingua franca (ELF) TC projects. The results cover language, culture, and 21st-century skills, and determine whether TC can be an efficient FL learning approach that satisfies the 21st-century demands, contributing to the ongoing debate on the future of FL and L2 language education.

- Federica Longo, from Nova Gorica, analyzes the features of contemporary Russian netspeak through linguistic corpora, using both paper and online dictionaries, traditional and Web corpora. It also investigates the diachronic evolution of Russian netspeak from 2011 to 2021, focusing on transliteration processes and derivational and inflectional morphemes. It shows the complexity of a new and constantly evolving language, with foreign loanwords struggling to adapt and integrate.

- Tamam Mohamad, from Syria, focuses on the salient qaf variable, which is realized as [q] and [ʔ], in Tartus city, Syria, and examines the distribution and gendered evaluations of these variants. Results show gender is significant in the urban region, but not in the rural regions. Social actors and spaces play a role in the acquisition of sociolinguistic variation.

- Giordano Stocchi, from Italy, explains how it is difficult for foreigners to acquire certain linguistic structures of Japanese language, such as the particles, ne, yo, and yone; broadly known as sentence-final particles. To improve JFL (Japanese as Foreign Language) learners’ Interactional Competence, he creates a project to develop class teaching materials using a corpus of spontaneous talk and translanguaging activities on sentence-final particles.

- Siqing Mu, from China, aims to elucidate the role of translanguaging in feedback across various educational contexts and highlight the importance of combining translingual practices and corrective feedback in target language skills and learning autonomy. The author reviews 22 peer-reviewed studies published between 2017 and 2022.

- Maria Ducoli, from Italy, provides an overview of the state of the art to support language policies that encourage bilingualism and multilingualism, focusing also on language disorders and clinical population.

- Metodi Efremov, from Nova Gorica, proposes a design to test the effect of cross-linguistic influence on heritage Macedonian speakers’ metalinguistic ability to judge the grammaticality of generic plural nouns in their heritage language. He predicts that French-Macedonian speakers will judge generic bare plural NPs as grammatical, while English-Macedonian speakers will find definite ones as ungrammatical. If structural overlap decides the direction of transfer, French-Macedonian speakers will judge generic bare plural NPs as ungrammatical and English-Macedonian speakers will find the opposite effect.

- Oana Puiu, from Romania, explores the translation of person deixis from English to Romanian in the context of the World Health Organization’s discourse on the Coronavirus pandemic. It uses discourse analysis and documentary analysis to investigate the heavy use of pronominals “I”, “we” and “you” and their functions and grammatical encoding.

- Azzam Alobaid, from India, investigates the claim that the greater number and range of L2 chunks that learners can accumulate over time can potentially contribute to the development of their L2 complexity. The three objectives are to build a linguistic corpus of previously collected data from Arabic-speaking ESL learners who were exposed to one ICT (Information and Communications Technology) multimedia learning tool (e.g., YouTube), and to examine their L2 development of lexical and grammatical complexity. The methodology for data analysis involves computer-based empirical analyses of language use.

- Concluding remarks

This paper explores the potential of multilingual practices in a multilingual classroom to facilitate the learning of linguistic theoretical tools and the development of metalinguistic thought. We propose that it is essential to provide a solid foundation of basic concepts, such as phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, to establish a common ground. Indeed, using concrete linguistic examples from everyday language to illustrate abstract theoretical concepts strengthens students’ metalinguistic awareness and reinforces their acquisition of linguistics.

Translanguaging, a technique for teaching a second language, is a useful tool for metalinguistic assessment. The concept of translanguaging is revolutionizing the study of language and society, and analyses of multilingualism are shifting from a focus on named languages to a focus on the actual linguistic practices of individuals, which is also known as “multilingualism from below” (Pennycook & Otsuji, 2015; Vogel & García, 2017). Language practices need to be studied in relation to socio-historical, political, and economic conditions that produce them, and challenging standard language ideologies. While translanguaging is becoming common in everyday communication, schools and other institutions still prioritize academic language, which can limit opportunities for bilingual students; however, translanguaging is obtaining benefits from multimodalities and human-technology interaction (Vogel & García, 2017). The role of multilingualism and the application of translanguaging are described in how they were developed within the “International Summer School on Bilingualism and Multilingualism” (ISSBM 2022), a linguistic summer school with students from 23 different countries. Multilingualism played a crucial role in strengthening students’ ability to refer to metalinguistic concepts and to deal with them in a scientifically valuable way.

In this article, we have discussed how linguistics as a discipline can serve as a useful laboratory for translanguaging practices, particularly in academic contexts. Science and academia are inherently multilingual, and linguistics is the discipline that can and should most readily embrace this union of languages and cultures. We have analyzed ISSBM 2022 in which hybrid mode has been implemented, demonstrating also how technologies, further developed following the COVID-19 pandemic, can help us bridge potentially distant languages and cultures. Indeed, the pandemic has forced many educational institutions and workplaces to adopt remote communication technologies, which has led to new opportunities for translanguaging practices. With participants and collaborators joining from different locations around the world, online meetings can naturally involve multiple languages and language varieties, and this can be a productive space for translanguaging. Participants can use different languages to express themselves, understand others, and negotiate meaning, which can lead to greater collaboration and understanding. Furthermore, online communication tools have features that can help facilitate translanguaging practices. For example, the chat function can be used for written communication in different languages, and participants can use the translation feature to understand messages in their own language. Additionally, breakout rooms can be used to allow smaller groups to work on tasks or discussions in different languages, which can be beneficial for language learners or for those who feel more comfortable speaking in a certain language.

This publication represents a culmination of the activities described in the preceding chapters. During the summer school, students were provided with a platform to showcase their research, which in turn was evaluated by both their peers and instructors. Of particular note is the innovative research session which allowed all participants, whether anonymously or not, to provide constructive criticism and feedback on aspects such as the style, clarity, and basic premises of each presentation. This open forum also provided an opportunity for individuals not presenting their own research to engage actively in the session. Following the feedback received during the aforementioned research session, students were given the opportunity to contribute to this book by composing a chapter on their studies. These submissions were then subject to further review by experts, who offered additional insights and guidance for improvement.

To conclude, it is our pleasure to extend our warmest wishes to the readers of this product. We sincerely hope that you will enjoy this book of proceedings, which is the result of a unique and valuable experience in the context of a multilingual summer school. As you delve into the various chapters, we hope that you will find a wealth of insights and ideas that will inspire your own research and broaden your understanding of the topics covered. This book represents the culmination of the hard work and dedication of the organizers, presenters, and participants of the summer school, and we are honored to be able to share it with you.

References

Augustsson, G., & Boström, L. (2012). A theoretical framework about leadership perspectives and leadership styles in the didactic room. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 2(4), 166-186.

Augustsson, G., & Boström, L. (2016). Teachers’ leadership in the didactic room: A systematic literature review of international research. Acta Didactica Norge-tidsskrift for Fagdidaktisk Forsknings-og Utviklingsarbeid i Norge, 10(3).

Baker, C. (2001). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. Bristol, U.K.: Multilingual Matters.

Beres, A. M. (2015). An overview of translanguaging: 20 years of ‘giving voice to those who do not speak’. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 1(1), 103-118.

Bialystok, E. (1988). Aspects of linguistic awareness in reading comprehension. Applied Psycholinguistics, 9, 123-139.

Bloor, T. (1986). What do language students know about grammar? British Journal of Language Teaching, 24, 157-160.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (Eds.). (2015). Multilingual education. Cambridge University Press.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Teaching English through pedagogical translanguaging. World Englishes, 39(2), 300-311.

Cornillie, F., Clarebout, G., & Desmet, P. (2012). The role of feedback in foreign language learning through digital role playing games. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 34, 49-53.

Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching?. The Modern Language Journal, 94(1), 103-115.

Dehghanzadeh, H., Fardanesh, H., Hatami, J., Talaee, E., & Noroozi, O. (2021). Using gamification to support learning English as a second language: a systematic review. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(7), 934-957.

Dobao, A. F. (2012). Collaborative writing tasks in the L2 classroom: Comparing group, pair, and individual work. Journal of second language writing, 21(1), 40-58.

El Euch, S., & Huot, A. (2015). Strategies to develop metalinguistic awareness in adult learners. In WEFLA 2015, International Conference on Foreign Languages, Communication and Culture (pp. 27-29).

Fisher, L., Evans, M., Forbes, K., Gayton, A., & Liu, Y. (2020). Participative multilingual identity construction in the languages classroom: A multi-theoretical conceptualisation. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(4), 448-466.

García, O., & Lin, A. M. (2017). Translanguaging in bilingual education. Bilingual and Multilingual education, 117-130.

García, O., & Sylvan, C. E. (2011). Pedagogies and practices in multilingual classrooms: Singularities in pluralities. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 385-400.

García, O., Wei, L. (2014). Language, Bilingualism and Education. In: Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Palgrave Pivot, London.

Gass, S. M. (2017). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. Routledge.

González-Lloret, M. (2019). Technology and L2 pragmatics learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 39, 113-127.

Koda, K. (2005). Learning to Read Across Writing Systems: Transfer, Metalinguistic Awareness, and Second-language. Second Language Writing Systems, 11, 311.

Künzli, R. (2000). German Didaktik: Models of Re-presentation, of Intercourse, and of Experience. In I. Westbury, S. Hopmann, & K. Riquarts (Eds.), Teaching as a reflective practice: the German Didaktik tradition (pp. 41–54). Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Lai, K. W. K., & Chen, H. J. H. (2021). A comparative study on the effects of a VR and PC visual novel game on vocabulary learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-34.

Li, Y., Ying, S., Chen, Q., & Guan, J. (2022). An Experiential Learning-Based Virtual Reality Approach to Foster Students’ Vocabulary Acquisition and Learning Engagement in English for Geography. Sustainability, 14(22), 15359.

Liang, W., & Fung, D. (2021). Fostering critical thinking in English-as-a-second-language classrooms: Challenges and opportunities. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 39, 100769.

Livingstone, C. (1983). Role Play in Language Learning. Longman, 1560 Broadway, New York, NY 10036.

Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Ritchie, T. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of Language Acquisition. Vol. 2: Second Language Acquisition, Academic Press, New York (1996), pp. 413-468

MacGregor, M., & Price, E. (1999). An exploration of aspects of language proficiency and algebra learning. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30(4), 449-467.

Malakoff, M. E. (1992). Translation ability: A natural bilingual and metalinguistic skill. In Advances in psychology (Vol. 83, pp. 515-529). North-Holland.

McDonough, K. (2004). Learner-learner interaction during pair and small group activities in a Thai EFL context. System, 32(2), 207-224.

Omar, S. F., Nawi, H. S. A., Shahdan, T. S. T., Mee, R. W. M., Pek, L. S., & Yob, F. S. C. (2020). Interactive Language Learning Activities for Learners’ Communicative Ability. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(4), 1010-1016.

Pennycook, A., & Otsuji, E. (2015). Metrolingualism: Language in the city. Routledge.

Pica, T. (1994). Research on negotiation: What does it reveal about second‐language learning conditions, processes, and outcomes?. Language Learning, 44(3), 493-527.

Pradono, S., Astriani, M. S., & Moniaga, J. (2013). A method for interactive learning. CommIT (Communication and Information Technology) Journal, 7(2), 46-48.

Richard-Amato, P. A. (1988). Making It Happen: Interaction in the Second Language Classroom, From Theory to Practice. Longman Inc., 95 Church St., White Plains, NY 10601-1505..

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Roehr-Brackin, K. (2018). Metalinguistic awareness and second language acquisition. Routledge.

de Haro, E. F., Delgado, M. P. N., & López, A. R. (2012). Consciencia metalingüística y enseñanza-aprendizaje de la composición escrita en educación primaria: Un estudio empírica. = Metalinguistic awareness and the teaching-learning processes of text composition at primary school: An empirical study. Rivista di Psicolinguistica Applicata, 12(1-2), 25-46.

Smith, N. C. (2012). Choosing How to Teach & Teaching How to Choose: Using the 3Cs to Improve Learning. Bennett & Hastings Publishing

Talalakina, E. (2015). Fostering Positive Transfer through Metalinguistic Awareness: A Case for Parallel Instruction of Synonyms inLl and L2. Journal of Language and Education, 1(4), 74-80.

Tunmer, W.E., Herriman, M.L. (1984). The Development of Metalinguistic Awareness: A Conceptual Overview. In: Tunmer, W.E., Pratt, C., Herriman, M.L. (eds) Metalinguistic Awareness in Children. Springer Series in Language and Communication, vol 15. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Tran, H. Q. (2018). Language alternation during L2 classroom discussion tasks. Conversation analysis and language alternation: Capturing transitions in the classroom, 165-182.

Turnbull, B. A. (2015). The effects of L1 and L2 group discussions on L2 reading comprehension (Doctoral dissertation, University of Otago).

Vogel, S., & García, O. (2017). Translanguaging, In G. Noblit & L. Moll (Eds.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wenling, L., Anderson, R. C., Nagy, W., & Houcan, Z. (2002). Facets of metalinguistic awareness that contribute to Chinese literacy. Chinese Children’s Reading Acquisition: Theoretical and Pedagogical Issues, 87-106.

Woll, N. (2018). Investigating dimensions of metalinguistic awareness: what think-aloud protocols revealed about the cognitive processes involved in positive transfer from L2 to L3. Language Awareness, 27(1-2), 167-185.

[1] https://sites.google.com/view/issbm2022-across/home