3 A corpus-based analysis of contemporary Russian netspeak: can corpora help us predict the future of a language?

Federica Longo

University of Nova Gorica, Center for Cognitive Science of Language, Nova Gorica, Slovenia

federica.longo@ung.si

The globalized use of the Internet has led to the birth of netspeak, the language used on the Internet and Social Media, which has unique characteristics, typical of both spoken and written language. This study analyzes the features of contemporary Russian netspeak through linguistic corpora. Both paper and online dictionaries, traditional and Web corpora were used for this survey; this has made it possible to carry out a comparative analysis between these tools, to evaluate which is more suitable for analyzing the target language. Furthermore, the use of Web corpora, allowed us to investigate the diachronic evolution of Russian netspeak, from approximately 2011 to 2021. The analysis focused on the different transliteration processes involving more than 300 loanwords, as well as the investigation of different derivational and inflectional morphemes attached to English transliterated loanwords and roots. This research aimed to establish whether a diachronic corpus-based analysis of Russian netspeak can help us to forecast which standard form will be established over time, making predictions on future developments of the language. An incredibly articulated and multifaceted picture emerges, which shows all the complexity of a new and constantly evolving language, in which foreign loanwords struggle to adapt and integrate into the target language, giving rise to numerous variants of the same word.

Keywords: Corpus Linguistics; Corpus-based analysis; Contemporary Russian netspeak; Loan words.

- Introduction

Computerization and the digital revolution have enabled significant advancements in all aspects of human life. With the advent of computers and digital software, corpus linguistics has flourished to the extent that some authors refer to a true “renaissance of work in Corpus Linguistics” (Volk, 2002: 255). In fact, it has undergone a complete transformation, both in terms of the amount of data that can be processed and the times of interrogation of these data.

The literature provides various definitions of corpus linguistics:

Corpus linguistics is the investigation of linguistic research questions that have been framed in terms of the conditional distribution of linguistic phenomena in a linguistic corpus. (Stefanowitsch, 2020: 56)

A Glossary of Corpus Linguistics states:

According to McEnery and Wilson (1996: 1) it is the study of language based on examples of “real life” language use and a methodology rather than an aspect of language requiring explanation or description. (Baker et al., 2006: 50)

In other words, corpus linguistics investigates language phenomena through quantitative and/or quantitative empirical analyses, using linguistic corpora, electronic text databases representative of natural language. Corpus analysis can provide insights into linguistic patterns and structures, and can be used to investigate a wide range of linguistic phenomena, such as syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and discourse.

If computerization enabled the first corpus linguistics revolution, the development of the Internet and the Web “has sparked a second Corpus Revolution” (Rundell, 2008: 26). Kilgarriff and G. Grefenstette published an article titled Introduction to the Special Issue on the Web as Corpus (Kilgarriff & Grefenstette, 2003) to demonstrate that the Web can be used as a linguistic corpus to conduct linguistic researches. The provocative formula “Web as Corpus” soon became widespread, appearing in the works of numerous authors including Volk (2002), Baroni and Bernardini (2006), Lüdeling et al. (2007), Ferraresi (2009), Lew (2009), and Gatto (2009, 2014).

Kilgarriff and Grefenstette’s intuition led linguists to think about a new denomination for this branch of corpus linguistics, which began to take shape in the early 2000s: D. Crystal was the first who introduced the term “Internet Linguistics” (Crystal, 2004). In 2005, G. Bergh proposed the variant “Web Linguistics” (Bergh, 2005). Web Linguistics, or Internet Linguistics, is a subfield of corpus linguistics that makes use of the World Wide Web for linguistic researches.

Among the most popular current trends, we mention the Corpus-based Language Teaching and Learning, which aims to identify common errors and language learners’ difficulties, in order to develop appropriate teaching materials and activities. The Russian Learner Corpus[1] (RLC), the Corpus of Russian Student Texts[2] (CoRST), and the RUssian LEarner Corpus of Academic Writing[3] (RULEC) are just few examples. Furthermore, this issue has been addressed by numerous linguists, as Chahine and Uetova (2023), Callies and Götz (2015), Granger (2009), McEnery et al. (2019), and Tono (2003).

Another major subfield is Multimodal Corpus Linguistics that focuses on the analysis of multimodal data, including text, images, videos, and audio, to study sign language, verbal and nonverbal communication, and emotions. We highlight Russian Sign Language Corpus[4] (RSL) and the works of Lyakso et al. (2015), Abuczki and Ghazaleh (2013), Blache et al. (2009).

Finally, we mention Corpus-based Discourse Analysis, which uses corpus linguistics to study discourse patterns, including the structure, organization, and function of language in context. In this regard, we mention the works of Jaworska and Ryan (2018), and Al-Khawaldeh et al. (2017).

The present study falls under one of the new trends of corpus linguistics, the Computed-Mediated Communication (CMC) Corpus Linguistics, which analyses large corpora containing digital communication texts, such as instant messaging, social media, email, and chatrooms, to identify the patterns and characteristics of the netspeak, and to investigate how these patterns change over time and across different contexts. For a detailed insight on this issue see Longo (2021).

Particularly, the research focuses on the analysis of contemporary Russian netspeak.

The netspeak, also known as weblish, globespeak, digispeak, chatspeak, and cyberspeak, is the language of the World Wide Web, which has unique characteristics, typical of both written and spoken language. Since the early 2000s, D. Crystal has addressed this question, noting that some academics had already described the Internet language as “written speech” and a mode to “write the way people talk” in the 1990s (Crystal, 2004: 25).

According to Crystal, what distinguishes spoken language from netspeak is the lack of simultaneous feedback, which determines the absence of another characteristic typical of speech, the listener’s simultaneous reactions, such as head nods, interjections, and nonverbal language of approval or dissent. Furthermore, in speech, the conversation can overlap or be interrupted, whereas in messages, the pace of the conversation is typically slower.

Similar to written language, punctuation, capital letters, and emoticons compensate for the lack of intonation, tone of voice, and pauses. Moreover, one feature that makes the netspeak more akin to written language, is the possibility of thinking of a structured discourse, erasing, modifying and reviewing what has been written.

Another distinguishing feature of netspeak is the use of emoticons, pictures, and gifs to express emotions, facial expressions, and gestures. Interestingly, these contents have changed the way in which other people’s messages are perceived or interpreted: without any type of emoticon, messages can be perceived as cold, detached, or even aggressive (Gunraj, 2016).

Taking everything into account, various studies on netspeak have revealed that it has characteristics more akin to the written language than the spoken one (Crystal, 2004; Johannessen and Guevara, 2011).

With regard to Russian netspeak, object of this investigation, different ways of transcribing English loanwords, the use of foreign loanwords as roots to create various forms of derived adjectives and verbs were observed.

Our goal is to determine whether a diachronic corpus-based analysis of Russian netspeak can help to predict which standard form will be established over time and determine future linguistic developments. Furthermore, a comparative analysis among the various research tools used, such as paper and online dictionaries, traditional and web corpora, was carried out in order to determine which of these is the most appropriate and up-to-date to investigate the Russian language in its contemporaneity.

- Methods

2.1 Materials

The 4th edition of Zanichelli Italian-Russian dictionary Kovalev (2014) and two online dictionaries, Vikislovar’[5] and Academic.ru[6] were used as research tools for this analysis.

As regards the corpora, we employed two sub-corpora of the Nacional’nyj Korpus Russkogo Jazyka (NKRJa)[7], the Main Corpus and the Spoken Corpus, and two Web corpora, the ruTenTen11 and the ruTenTen17, both accessible through the online platform Sketch Engine. A third Sketch Engine Web corpus, the Timestamped JSI web corpus 2014-2021 Russian, was used when the analysis generated unclear results.

The NKRJa is the primary corpus of the Russian language. It now contains 1.9 billion tokens, spread among 15 sub-corpora. The Main Corpus and the Spoken Corpus include 374 and 13.4 million tokens, respectively.

The Russian Web Corpora, abbreviated ruTenTen11 and ruTenTen17, contain 14.5 and 9 billion tokens, respectively. Finally, there are approximately 5.5 billion tokens in the Timestamped JSI web corpus 2014-2021 Russian.

2.2 Procedure

Firstly, to search for lemmas appropriate for our analysis, we entered the following query on Yandex, the Russian search engine: Sleng molodëži 2021, Molodëžnij sleng 2021, Molodëžnij žargon, Russkij žargon molodëži, Modnye slova 2021, Samye populjarnye slova 2021[8].

Based on the findings, we examined a variety of dictionaries and online resources, and we created a preliminary list of lexemes to be analyzed, by cross-analyzing the data frequency.

The data was further filtered, and some lexemes were removed, since they were deemed offensive or obscene. Over 300 lexical items are included in the final “List of analyzed lemmas”, which can be found in the Appendix.

Subsequently, we created an analysis chart to report the following data:

- Meaning and definition of the lemma or of the English loanword in Russian;

- Gender/declension/conjugation of the lemma;

- Compounds and/or derived lemmas;

- Etymology of the lemma/loan;

- Type of linguistic interference (loan, total or partial calque, etc.);

- Autochthonous Russian lemmas and synonyms;

- Frequency of the analyzed lemma on both print and online dictionaries;

- Frequency of the analyzed lemma on the Main Corpus and Spoken Corpus of NKRJa;

- Frequency of the analyzed lemma on ruTenTen11 and ruTenTen17;

- Concordances;

- Examples of usage and translation;

- Personal notes and considerations.

- Results and discussion

The findings from the data analyses will be examined in this section, organized into distinct sub-sections for clarity.

3.1 Different transcriptions of the English loanwords

Various methods of transcribing borrowings from Latin characters of the English language to Cyrillic emerged during the analysis. The greatest variation has been identified at the level of phonetic and orthographic realization of English loanwords. These observations will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections.

3.1.1 Vowel alternation of Э (/ɛ/) and E (/je/ or /je/)

The vowel [e] is represented by two different graphemes in Russian: “э” denotes a strong vowel that is pronounced open (/ɛ/), while “e” denotes a weak vowel that softens the consonant that comes before it (/je/ or /je/).

The presence of these two vowels in the Russian language results in the coexistence of different transcriptions for the same loanword (see Table 1) and this is one of the most frequent phenomena.

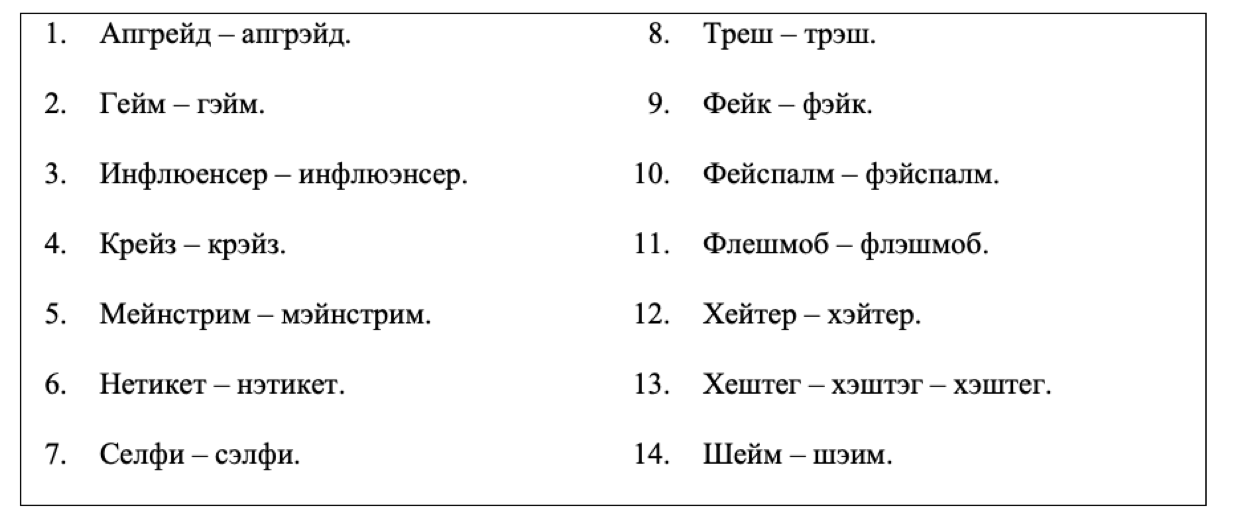

Table 1. Lexical items occurring with graphemes е and э.

The frequency analysis revealed that 80% of the above lexical items are transcribed using the grapheme “e”: specific mention is made of инфлюeнсeр (“influencer”), нетикет (“netiquette”), апгрейд (“upgrade”), гейм (“game”), as well as the nouns крейз (“craze”), мейнстрим (“mainstream”), селфи (“selfie”), фейспалм (“facepalm”), фейк (“fake”), флешмоб (“flash mob”), хейтер (“hater”) and their related derived verbs and adjectives. Instead, трэш (“trash”), хэштег (“hashtag”), and шэйм (“shame”) are typically spelled with the grapheme “э”.

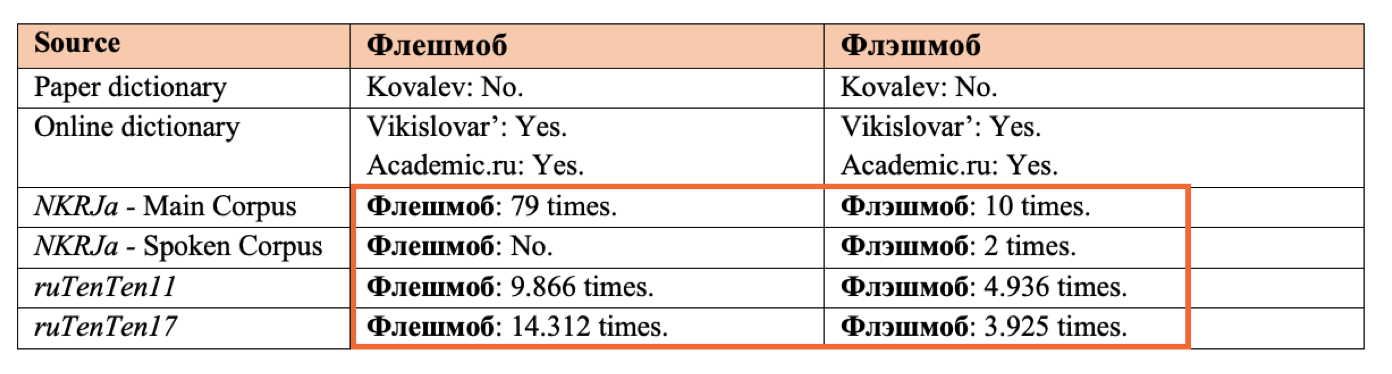

For sake of clarity, Table 2 below repots an example of the analysis of the frequency for the variants флешмоб and флэшмоб.

Table 2. Data from the analysis of флешмоб and флэшмоб (“flash mob”).

According to the data of the above table, the most frequent transcription of “flash mob” is the one with the grapheme “e”. If we consider the English phonetic transcription, /ˈflæʃ mɒb/, the front vowel /æ/ is realized in флешмоб with /e/, but the same does not hold with хэштег and тpэш, in which the original /æ/ is transliterated /э/. At the orthographic level, the Russian manual Rozental’ reports that the grapheme “e” is used in Russian after a consonant and the vowel “i” in the root of words, while э is used in the root of words after vowels, except “i” (Rozental’, 2010: 32). Again, хэштег and тpэш violate this rule.

The initial hypothesis held that there was a relationship between the English phoneme, or phoneme sequences, and the realization of a particular grapheme in Russian transcription. However, no correlation has been found to support or refute this theory. Although there is a definite preference for using the grapheme “e”, neither the original phoneme, the stress position, nor the number of syllables in the lemma have any bearing on the grapheme used in the transcription. Even Russian orthographic rules are not always strictly observed, reflecting the complex and multifaceted picture of loan transcriptions in Russian.

3.1.2 Consonant alternation of C (/s/) and З (/z/)

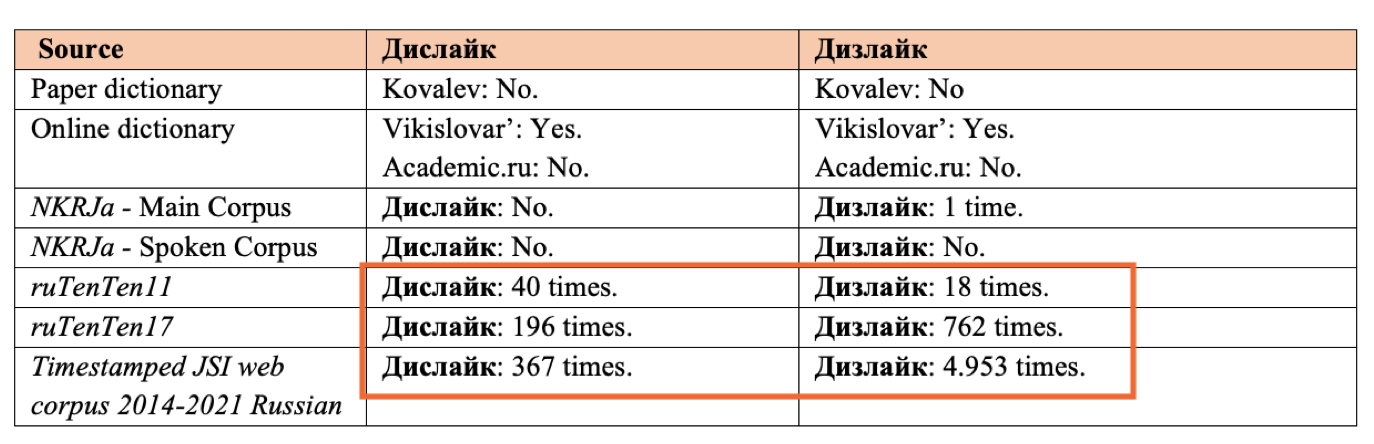

In Russian the voiceless alveolar fricative (/s/) is represented by the grapheme “с”, while the voiced alveolar fricative (/z/) is represented by the grapheme “з”. These two consonants are thus in “voiceless-voiced” opposition. During the analysis, a double transcription of the English word dislike emerged: the variants дислайк and дизлайк.

Since dislike in English is pronounced /dɪˈslaɪk/, with a voiceless alveolar fricative, we should expect the Russian transcription дислайк. Concurrently, according to Russian orthographic and phonological rules that govern the use of prefixes ending with -з and -c, the voiced fricative -з must be used before vowels and voiced consonants, as it is in this case (Rozental’, 2010: 51). In other words, each type of transcription had a 50% chance of occurring; to identify which one has been successfully established in modern Russian netspeak, we employed corpus analysis.

Table 3. Data on the frequency of дислайк and дизлайк (“dislike”).

Despite the extremely low frequency of data, Table 3 shows that the transliteration дизлайк, with the voiced alveolar fricative, is favored in Russian transcription. This demonstrated that dislike has undergone a deep process of russification and adaptation, and is now written according to Russian phonological and orthographic rules, rather than the English original pronunciation.

3.1.3 Compound nouns that are hyphenated or written as a single lexical item

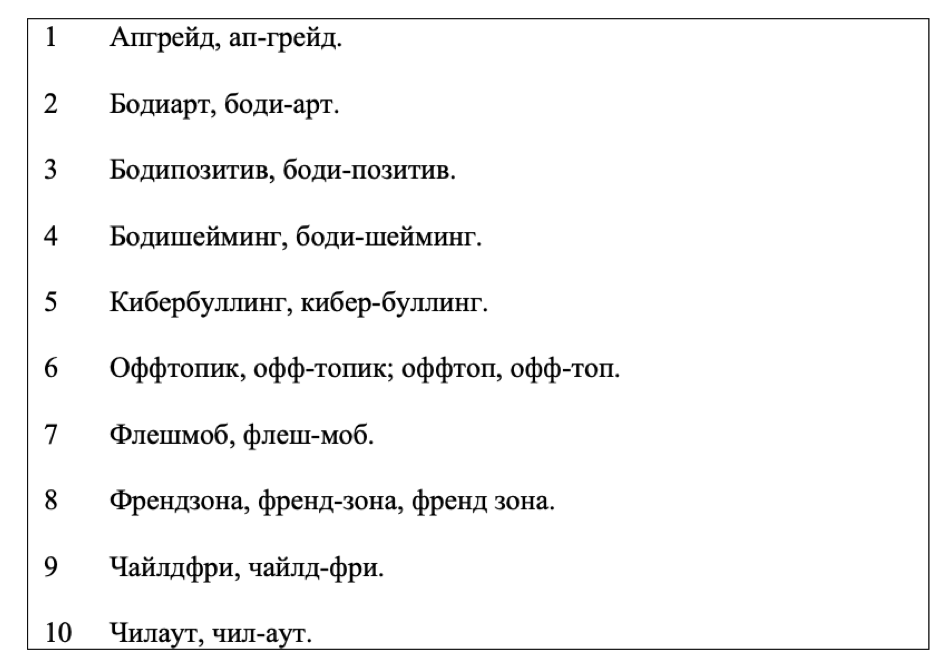

As shown in Table 4, different ways of transcribing English compound words resulted from the investigation.

Table 4. Different realizations of English compound words.

Particularly intriguing are those compounds with “body” such as бодиарт (“bodyart”), and the variant боди-арт (“body-art”), бодипозитив (“bodypositive”) and боди-позитив (“body-positive”), and ultimately бодишейминг (“bodyshaming”) and боди-шейминг (“body-shaming”). Although they are composed of the same elements, these lexemes are transcribed differently: unlike in English, боди-арт is mainly written in Russian with a hyphen. In contrast, the nouns бодипозитив and бодишейминг are both transcribed as a single lexical item, while in English they are spelled body-positive and body-shaming, respectively.

Similarly, оффтопик (“off-topic”), which is written in English separated by a space or a dash, is written in Russian as a single noun. Interestingly, the analysis revealed a preference for the word’s truncated version, оффтоп, which is nonexistent in English.

Regarding the word child-free, it is worth noting that English compounds containing the adjective “-free” as the second element of the compound are typically written with the two elements of the word separated by a hyphen; examples include sugar-free, tax-free, fat-free, duty-free, etc. The word чайлдфри, written attached, has established itself in the Russian language, contrary to the English standard and our expectations.

In a similar vein, the compound flash mob, typically spelled in English with spaces between words, has established itself in Russian as the single lexical itam флешмоб.

An additional intriguing example is chill out, which in English can be either a noun, an adjective, or a phrasal verb. Depending on its function in a sentence, it is written differently: when it is a noun or an adjective, the word chill and the preposition out are separated by a hyphen, while when it is a phrasal verb, they are separated by a space. In Russian, the noun is not only written as a single lexical item, but one of the two lateral liquid consonants “l” of chill is also omitted, resulting in чилаут.

Апгрейд (upgrade), кибербуллинг (cyberbulling), and френдзона (friend zone) are among those words that retain their original English transcription and are written in Russian as a single lexical item.

In summary, Russian loans differ significantly in spelling from the original English words in the majority of cases: the analyses revealed that only 30% of the time the spelling is completely respected. Furthermore, the transcription of оффтоп and чилаут differs significantly from the original English. The corpus analysis has allowed us to determine which transcription mode has been established in the modern Russian language.

3.2 Nouns: word formation processes, loans, and irregularities that emerged

Nouns are the most frequent morphological category among the examined lexemes. The results of the corpora analysis will be illustrated in the following subparagraphs.

3.2.1 Transliterated loanwords

The most common phenomena, found in forty-one cases, are the transliterated loans. They are typically luxury loans, i.e. nouns that already have a lexical equivalent in the target language, but they are used to add an exotic or prestigious nuance to speech, in technical languages, or by a small circle of people who share a specific linguistic code.

These loans are subjected to significant inflectional and derivational affixation processes: not only they are regularly declined, whereas in the past most borrowings were left unchanged, but they also give rise to new derivative adjectives and verbs.

Loan usage tends to regularize over time: if some borrowings initially displayed two or more types of transcriptions, then they consolidated into one definitive form, as observed in the previous paragraph. The word селфи (selfie) is intriguing: according to the corpus analysis, it was initially a regular declinable noun, but over time it became firmly established in the Russian language as an invariant, non-declinable noun.

Another interesting case is the noun трэш, which, according to Vikislovar’, has two declensions, with a different accent and only in the singular form, i.e. трэш would be part of the nomina singularia tantum category; however, corpus analysis revealed that this noun is declined even in the plural number.

3.2.2 Loanwords deriving from English nomina agentis and nomina actionis ending in -er

The nomina agentis are nouns that refer to the entity that performs the action, whereas the nomina actionis are nouns that refer to the action itself. For their creation, each language has its own derivational morphemes: in English, a derivational model frequently used is “verb + -er/-or” (e.g. kill → killer, translate → translator), whereas in Russian the most common are “verb + -тель, -чик, -щик, -ич, -ок, -ник, etc.” (e.g. читать → читатель “read → reader”, переводить → переводчик “translate → translator”).

During the investigation, twenty-two English nomina agentis and actionis ending ending in -er were found, transliterated into Russian as borrowings, most frequently as luxury loanwords. In other words, the foreign roots of these lexemes are not adapted to the target language by using standard Russian derivational suffixes; nouns are simply transliterated and declined as strong masculine nouns ending in –ер (“-er”).

The words абьюзер (“abuser”), апгрейдер (“upgrader”), блогер (“blogger”), кибербуллер (“cyberbuller” – note that this word does not exist in English), геймер (“gamer”), инфлюенсер (“influencer”), лайкер (“liker”), лайфхакер (“lifehacker”), лузер (“loser”), пранкер (“pranker”), спойлер (“spoiler”), стайлер (“styler”), стример (“streamer”), траблмейкер (“troublemaker”), фейкер (“faker”), фолловер (“follower”), хейтер (“hater”), and юзер (“user”) are just few examples.

3.2.3 Russified English loanwords with the suffix -ств(o), denoting abstract neuter nouns

Numerous nouns in Russian have the derivational pattern “Adjective/noun root + suffix -ств(о) → Neuter abstract noun”.

These neuter nouns ending in -ств(o) typically denote a union or a group of people, usually quite numerous (братство “brotherhood”, дворянство “nobility”), an institution or organization (агентство “agency”, посольство “embassy”), an abstract quality, typical of animate beings, (богатство “wealth”, изящество “elegance”), a person endowed with the characteristics expressed by the root of the noun (божество “divinity”, ничтожество “nullity”), and people’s working activities (акушерство “obstetrics”).

During the analysis, six nouns ending in -ств(o) were discovered, the root of which is a transliterated English loanword. Specifically, these neuter nouns indicate an abstract category, such as блогерство (“a set of people belonging to the category of bloggers”), геймерство (“a set of people belonging to the category of gamers”), лузерство (“a set of people belonging to the category of losers”), спойлерство (“a group of people who spoils”), хейтерство (“a set of people belonging to the category of haters”) e хипстерство (“a group of people belonging to the category of hipsters”), deriving from the nomina agentis blogger, gamer, loser, spoiler, hater, and hipster, respectively. Although they don’t appear frequently in the corpora under investigation, these Russified English loanwords provide an intriguing example of acclimation and integration into the Russian language. This derivational model is not particularly common, but it has a strong possibility of becoming more widespread over time.

3.2.4 Transliterated loanwords and partial calques having the same meaning

During the research, some compound nouns with the same meaning but different word forms were found: селфи-стик and селфи-палка (“selfie stick”) and the compound nouns фейк-ньюс, фейкньюс, and фейк-новости (“fake news”).

Селфи-стик and фейк-ньюс or фейкньюс are fully transliterated loanwords, whereas селфи-палка and фейк-новости are linguistic partial calques. These are examples of the so-called endocentric compounds, which have a semantic head that carries the compound word’s semantic meaning, and a modifier that restricts the meaning of the word. In the case of селфи-палка and фейк-новости, only the modifiers cелфи- (“selfie-”) and фейк- (“fake-”) are transliterated loanwords, whereas the semantic head -палка (“stick”) and -новоcти (“news”) are linguistic calques.

It’s also worth noting that the word “news” is a pluralia tantum noun in English, and the calque in Russian was kept plural as well.

In the case of “selfie stick” the partial calque селфи-палка is more frequent than the transliterated loan селфи-стик. This trend is supported by data from ruTenTen17 and from the Timestamped JSI web corpus 2014-2021 Russian. On the contrary, the term “fake news” has spread widely in Russian as the transliterated loanword фейк-ньюс, rather than the partial calque фейк-новости. Data from ruTenTen17 and the Timestamped JSI web corpus 2014-2021 Russian confirm this trend.

3.3 Adjectives: derivational processes and different word forms with the same meaning

Numerous derived adjectives were identified during the analysis; in the following subsection, we will examine the phenomena observed in relation to this morphological category.

3.3.1 Adjectives derived from transliterated English loanwords

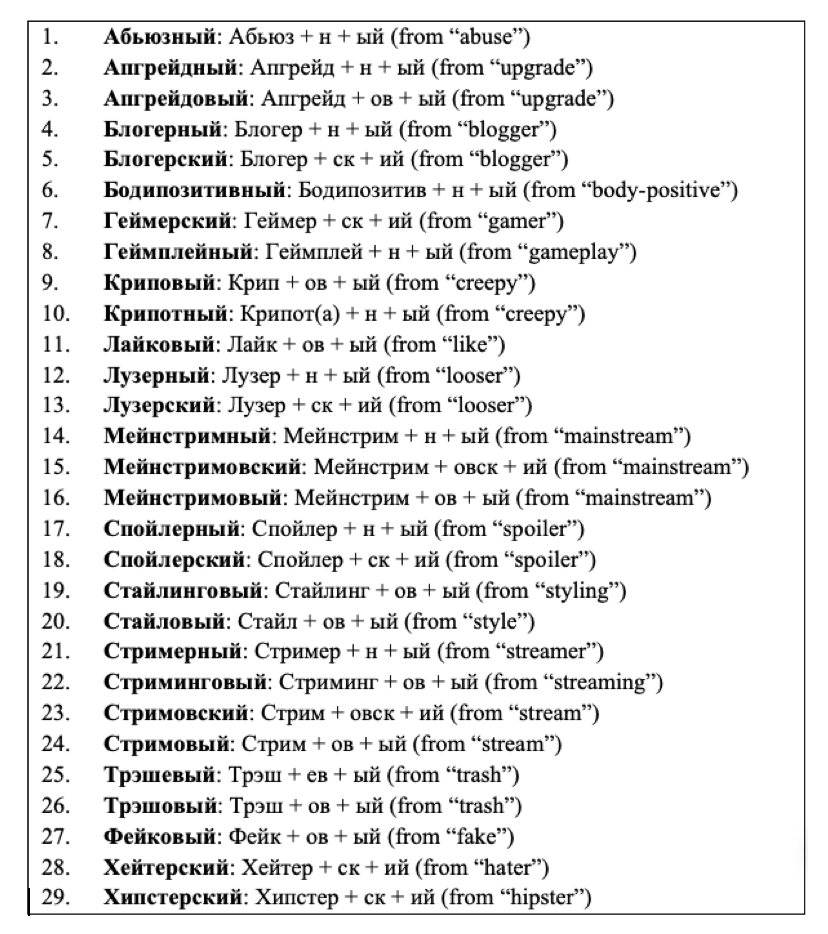

During the investigation, twenty-nine adjectives derived from transliterated English loanwords were discovered, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. The list of analyzed adjectives.

Adjectives are formed using the Russian derivational suffix -oв-/ -ев- in 38% of cases, the suffix -н- in 34.5% of cases, the suffix -ск- and -oвск- in 20.7% and in 7% of cases, respectively.

Additionally, ten of the analyzed adjectives derive from the previously mentioned English nomina agentis and actionis, whereas in two cases Russified adjectives derive from English nouns ending with the suffix -ing, namely стриминговый (стриминг + -ов- + ый), deriving from the noun “streaming”, and стайлинговый (стайлинг + -ов- + ый), deriving from the noun “styling”.

English nouns ending in -ing generally indicate an action, an activity, or the act of doing something, and the resulting Russified adjectives preserve this actionality in meaning.

Furthermore, some Russian adjectives having different derivational suffixes, but the same English root, were found.

This is the case of adjectives like апгрейдный and апгрейдовый, блогерный and блогерcкий, криповый and крипотный, лузерный and лузерcкий, мейнстримный, мейнстримовский and мейнстримовый, спойлерный and спойлерский, стримовский and стримовый, трэшевый and трэшовый, derived respectively from English nouns upgrade, blogger, loser, mainstream, spoiler, stream and trash.

In general, each derivational suffix has a specific meaning: namely, the suffixes -ев-/-oв- indicate belonging, the property of an object, a material, or technical terminology; the suffix -cк- denotes the relationship with a certain category or the belonging to the category itself; finally, the suffix -н- indicate a property related to an object, a phenomenon, an action, a place, being subject to an action or the result of an action, denoted by the root of the adjective.

Statistical analysis has helped to identify which adjective has become widely used in Russian; however, it must be kept in mind that this study focuses on Russian neologisms derived from English loanwords that are still evolving and integrating into the language. The integration of these new adjectives into the Russian language over time can be traced using corpus diachronic analyses.

3.4 Verbs: derivational and russification processes

During the analysis, three major trends concerning verb derivational processes emerged: verbs having English transliterated nouns, acronyms, or verbs as their root; different verb forms deriving from the same root, but belonging to different conjugations; finally, verbs derived from English loanwords and russified by adding the Russian suffix -cя to create the reflexive form of the verb.

These phenomena will be discussed in detail in the following subparagraphs.

3.4.1 Verbs derived from transliterated English loanwords

Several verbs deriving from English transliterated nouns, acronyms, or verbs were found during the analysis.

Only one of the forty examined verbs derives from an acronym. In fact, the English acronym ROFL (Rolling On the Floor Laughing), usually transliterated into Russian as РОФЛ, gives rise to the verb рофлить, which means “rolling on the floor laughing” or “laughing out loud”.

The major derivational suffixes used in verb formation are -a-, -и-, -ировa-, -ну-, and -ова-.

The derivational suffix -и- appears in 62.5% of cases, followed by the derivational suffix -а-, used in 15% of cases. The suffix -ну- is less common, used in 10% of cases, as are the suffixes -ова- and -ирова-, which appear in 7.5% and 5% of cases, respectively.

Derivational suffixes in Russian convey a specific meaning: the suffix -и- generally denotes the action denoted by the meaning of the verb’s root (рыбачить “to go fishing”, from рыба “fish”), the act of using an object or a tool, and atmospheric events (морозить “to frost”, from мороз “frost”), the manifestation of a quality denoted by the verb’s root (веселить “to amuse”, from веселье “amusement”), and many others. The suffix -a- forms denominal verbs, which typically denote a prolonged or repeated action (завтракать “to have breakfast”, from завтрак “breakfast”). The verbs created by the -ну- suffix frequently refer to a single, instantaneous, and momentary action, whereas the suffix -oвa- forms imperfective verbs that denote the act of doing something, devoting oneself to an activity, or being in a specific state.

The corpora analyzed revealed that these different nuances of meaning are preserved in these newborn verbs, but not always.

3.4.2 Verbs derived from the same root, but belonging to different conjugations

During the analyses, different variants of verbs deriving from the same English root have been discovered: first of all, form the English noun “upgrade” derive five different verb forms; these are the verbs апгрейдировать, апгрейднуть, and апгрeйтить, the reflexive verb апгрейдиться, and апгрейдить, the most frequent of all.

The English noun “game” also gave rise to two different Russian verbs, гамать and гeймить. Even though they may appear as verbs deriving from different foreign loanwords, the original word is, in fact, the same, i.e. “game”, transliterated in two different ways: гаме, as it is written in English, and гейм, as it is pronounced in English. Data analyses indicate that гамать is the most popular, but only further diachronic studies will be able to determine which of the two verbs will settle definitively in the Russian language.

Two Russified variants of the English verb “to dislike” were found: дизлайкать and дизлайкнyть. Дизлайкать is slightly more frequent than дизлайкнyть however, the corpus occurrences are so rare that accurate predictions cannot be made.

The verbs свайпать, свайпить and свайпнyть derive from the English verb “to swipe”, which means moving one’s finger across a touchscreen. The meaning of a single and instantaneous action may explain why свайпнyть is the most widespread variant of the three.

The verbs спoйлерить and спойлернуть derive from the verb “to spoiler”, which means to anticipate a part of a film, a TV series or a book, usually the ending. The most frequent variant is спойлерить, a trend confirmed by data from the Main Corpus, ruTenTen11 and ruTenTen17.

The verbs трoллировать and троллить derive from the English verb “to troll”, which means to provoke, instigate or annoy someone on the Internet, in a chat, forum, or blog. Трoллировать is rarely used: forty-one occurrences in ruTenTen11 and only fourteen in ruTenTen17, so it may be doomed to disappear in favor of the most popular variant троллить.

3.4.3 Verbs derived from English loanwords, turned reflexive by the suffix -ся

In Russian, reflexive verbs are formed through a process known as postfiksacija (“postfixation”), which differs from normal suffiksacia (“suffixation”) in that the reflexive particle -ся is added at the end of the verb, after the derivational suffixes that turn the root into a verb form.

Six out of the forty analyzed verbs during the investigation were reflexive and derived from transliterated English borrowing. These verbs frequently have a non-reflexive variant: as in the cases of агрить “to make angry, to provoke”, and the reflexive агритьcя “to get angry, to get annoyed”, the verb апгрейдить (or its many variants апгрейдировать, апгрейднуть and апгрейтить) meaning “to upgrade”, and the reflexive verb апгрейдитьcя “to upgrade yourself”, “to improve yourself”. The verb cелфить, which means “to take a selfie” has a reflexive variant селфиться, which means “to take a selfie of oneself”; the verb чилить, which means “to chill” has a reflexive but rarely used form, чилиться, which means “to chill oneself” (note that in English this verb is non-reflexive and intransitive).

The reflexive verb сорриться, which literally means “to apologize oneself”, is derived from the English adjective “sorry” and has the postfix -ся to make it reflexive. It’s an interesting case because in English there is no verb “to sorry”, instead other forms are used (namely, “to be sorry”, “to feel sorry” or “to say sorry”); therefore this verb has undergone a deep process of russification, originating from an English loanword and adapting to the model of the Russian reflexive verb извинятьcяIMP –извинитьсяPF (“to say sorry” in the imperfective and perfective forms, respectively).

- Conclusions

The preceding paragraph illustrated the results and discussions on the analysis of contemporary Russian netspeak, conducted using a variety of research tools, including paper and online dictionaries, traditional corpora, and web corpora. It was thus possible to investigate the peculiarities of the contemporary Russian language and, at the same time, to conduct a comparative analysis of the research tools.

As regards the various methods of transcribing loans, English loanwords are typically transcribed from Latin to Cyrillic characters as they are pronounced in English, rather than as they are written, resulting in a kind of phonetic transcription. However, we cannot legitimately speak of “phonetic transcription” because the transcription is not based on the IPA alphabet (International Phonetic Alphabet) and is far from being a scientific transcription method.

At the same time, if by “transliteration” we mean a transcription of a text according to an alphabetic system different from the original, we cannot even speak of it. Moreover, transliteration does not aim to give a phonetic interpretation, as it is in our case.

Based on findings, I am inclined to propose a new term, “phonetic transliteration” capable of gathering and combining the characteristics of both terms. This definition, in my opinion, is the most appropriate for the Russian language, because the English loans are indeed transliterated, but on the basis of their pronunciation.

Nouns are the most frequent loan; these are typically luxury loanwords that give rise to Russified derived and/or compound words. The presence of English nomina agentis and actionis ending in -er, transliterated and declined in Russian as masculine nouns ending in “-ер”, is an intriguing phenomenon: twenty-two of them were identified during the analysis.

Less common, but equally interesting, is the Russification of English nomina agentis ending in -er by adding the derivational suffix “-cтв(о)”, resulting in neuter nouns with an abstract meaning, indicating a union or a group of people. During the analyses we found out 6 of them.

Verbs are the second most productive morphological category: 40 different verb forms were identified during the analysis, most of which were derived from English nouns. The research revealed that there are different verb forms derived from the same loan, but depending on the derivational suffix used (-а-, -и-, -ирова-, -ну-, -ова-), these verbs acquire a specific nuance of meaning.

A fascinating phenomenon involves verbs derived from transliterated English loans, to which the suffix -cя is added, to make them reflexive; the most interesting case is the verb cорритьcя (from “sorry”), which has been adapted to the Russian reflexive model извинятьcя – извинитьcя (to apologise”), unlike the English language which uses formulas such as to be sorry, to feel sorry or to say sorry.

In terms of a comparative analysis of the research tools used, the study suggests that the paper dictionary is insufficient for searching for neologisms and foreign loans, as no lexeme under investigation was found. On the contrary, online dictionaries are perfectly adequate and up-to-date resources for researching modern language and slang. They are, however, unsuitable for linguistic analysis.

In terms of the two NKRJa sub-corpora, the Main Corpus is the most appropriate: in fact, it presented the occurrences of the searched word in 70% of the cases, whereas the Spoken Corpus only contained search results in 32.5% of the cases. Despite their undeniable utility, these two NKRJa sub-corpora cannot be compared to the web corpora used for the analyses in terms of data quantity and variety. RuTenTen11 and ruTenTen17 are the most effective tools for researching Russian neologisms and foreign borrowings: in 100% of cases, they contained occurrences of the searched word as well as several derived or compound lexemes. However, they are sometimes not very reliable and precise.

The provocative title of this paper clearly states our goal: to see if corpus analysis can help us predict future developments in Russian language. In general, a diachronic analysis of the linguistic corpus can be used to identify which standard form is consolidating in the target language, allowing predictions about the language’s future developments. Moreover, in the field of lexicography, this type of analysis can be extremely beneficial.

In conclusion, the research objectives were met. At the same time, some questions for future research remain unanswered: the pattern analysis of those verbs derived from loans, to determine whether they are adapted to the Russian language, via structural calque, or remain the same as the original English model; and the concordances’ analyses relating to the loans examined, to determine whether or not they are adapted to the target language. These are just a few examples of how vast and complex the field of study is: this research is not the end, but only the beginning.

Appendix

List of analyzed lemmas

- Абьюз, абъюз, абюз; абьюзер, абъюзер, абюзер; абьюзить, абъюзить, абюзить; абьюзный, абъюзный, абюзный.

- Агрить, агриться.

- Апгрейд, апгрэйд; апгрейд, ап-грейд; апгрейт, апгрэйт; апгрейдер, апгрэйдер; апгрейдинг, апгрэйдинг; апгрейдный, апгрэйдный; апгрейдовый, апгрэйдовый; апгрейденный, апгрэйденный.

- Апгрейдить, апгрэйдить; апгрейдиться, апгрэйдиться; апгрейднуть, апгрэйднуть; апгрейтить, апгрэйтить; апгрейдировать, апгрейдировать.

- Ауф.

- Байтить.

- Баттхерт, баттхёрт, баттхёртить, баттхертить.

- Блогер, блоггер; блогерский, блоггерский; блогерный, блоггерный; блогерство, блоггерство.

- Бодиарт, боди-арт.

- Бодипозитив, боди-позитив; бодипозитивный, боди-позитивный.

- Бодишейминг, боди-шейминг; бодишеймер, боди-шеймер.

- Буллинг, кибербуллинг, кибер-буллинг, кибербулинг, кибер-булинг; буллер, кибербуллер, кибер-буллер.

- Вайб, вайбер.

- Варик.

- Вписка.

- Гамать.

- Гейм, гэйм; гейминг, гэйминг; гейминговой, гэйминговой; геймер, гэймер; геймерский, гэймерский; геймерство; геймить, гэймить; геймиться, гэймиться; геймплей, гэймплей; геймплэй, гэймплэй; геймплейный, гэймплейный; геймификация, гэймификация.

- Дакфейс, дакфейсинг.

- Дислайк, дизлайк, дизлайкнуть, дизлайкать.

- Днюха.

- Жиза.

- Зашквар, зашквариться, зашкварить, зашкваренный, зашкваривания.

- Зумер.

- ИМХО.

- Инфлюенсер, инфлюэнсер.

- Краш.

- Крейз, крэйз; крейзи, крэйзи; крейзер, крэйзер; крейзинг, крэйзинг; крейзанутый, крэйзанутый; крейзовый, крэйзовый.

- Криндж, кринж; кринджовый, кринжовый.

- Крипово, крипота, криповый, крипотный.

- Кста.

- Кэп.

- Лайк, лайковый, лайкер.

- Лайфхак, лайфхакер, лайфхакинг.

- Лойс.

- ЛОЛ.

- Лузер, лузерство, лузерский, лузерный, лузерс.

- Мейнстрим, мэйнстрим; мейнстримовый, мэйнстримовый; мейнстримный, мэйнстримный; мейнстримовский, мэйнстримовский; мейнстриминг, мэйнстриминг.

- Муд.

- Музон.

- Нетикет, нэтикет.

- Офтоп, оф-топ; оффтоп, офф-топ; офтопик, оф-топик; оффтопик, офф-топик.

- ПМСМ.

- По фану.

- Пранк , пранкер, пранковать.

- РОФЛ, рофлить, рофлер.

- Свайп, свайпнуть, свайпать, свайпить, свайпинг, свайпс.

- Селфи, сэлфи; селфить, сэлфить; селфиться, сэлфиться; селфи-камера, сэлфи-камера; селфи-палка, сэлфи-палка; селфи-стик, сэлфи-стик.

- Сетикет.

- СЗОТ.

- Сорри, сорриться.

- Спойлер, спойлерство, спойлерить, спойлернуть, спойлерный.

- Стайл, стайлс, стайлер, стайлинг, стайлинговый, стайлиш, стайловый.

- Стрим, стример, стримерный, стриминг, стриминговый, стримить, стримовый,

стримовский. - Стэнить.

- Трабл, траблс, траблер, траблмейкер, траблшутинг, траблшутить.

- Трип, трипп, трипер, триппер, триперный, трипперный, триповый, триповать, трип-хоп, трип-хоповый трип-компьютер.

- Тролинг, троллинг; тролинговый, троллинговый; тролить, троллить; тролинговать, троллинговать; тролировать, троллировать.

- Треш, трэш; трешер, трэшер; трешевый, трэшевый; трешовый, трэшовый.

- Фейк, фэйк; фейковый, фэйковый; фейк-новости, фэйк-новости; фейк-ньюс, фэйк-ньюс; фейкньюс, фэйкньюс.

- Фейспалм, фэйспалм; фейспалмить, фэйспалмить.

- Флексить.

- Флуд, флудер, флудерский, флудинг, флудить.

- Флешмоб, флэшмоб; флеш-моб, флэш-моб; флешмобер, флэшмобер; флешмоббер, флэшмоббер; флеш-мобер, флэш-мобер; флеш-мобер, флэш-моббер.

- Фоловер, фолловер; фоловинг, фолловинг; фоловить, фолловить.

- Френдзона, френд-зона, френд зона.

- Хайп, хайповый, хайпануть, хайпер.

- Хейтер, хэйтер; хейтерить, хэйтерить; хейтить, хейтерс; хейтерство, хэйтерство; хейтинг, хэйтинг; хейтерский, хэйтерский.

- Хипстер, хипстерство, хипстерский.

- Хэштег, хэштэг, хештег.

- Чайлдфри, чайлд-фри, чайлд фри.

- Чапалах.

- Чекать.

- Челендж, челлендж; челенж, челленж; челенджер, челленджер, челенжер, челленжер.

- Чилл-аут, чиллаут, чил-аут, чилаут, чиллер, чиллерный.

- Чилить, чиллить; чилиться, чиллиться.

- Шейм, шэим; шейминг, шэйминг.

- Юзер, юзерский, юзать, юзаться.

- Юзернейм.

- Юзерпик.

- 7Я.

References

Abuczki, Á., & Ghazaleh E. B. (2013). An overview of multimodal corpora, annotation tools and schemes. Argumentum, 9, 86-98.

Al-Khawaldeh, N. N., Khawaldeh, I., Bani-Khair, B., & Al-Khawaldeh, A. (2017). An exploration of graffiti on university’s walls: A corpus-based discourse analysis study. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(1), 29-42.

Baker P., Hardie A., McEnery T. (2006). A Glossary of Corpus Linguistics, Edinburgh University Press.

Baroni M., & Bernardini S. (2004). BootCat: Bootstrapping corpora and terms from the web. In LREC (pp. 1313-1316).

Baroni M., & Bernardini S. (2006). WaCky! Working Papers on the Web as Corpus (Vol. 6). Gedit.

Baroni M., Bernardini S., Ferraresi A., & Zanchetta E. (2009). The WaCky wide web: a collection of very large linguistically processed web-crawled corpora. Language Resources & Evaluation, 43, 209-226.

Baroni, M., & Kilgarriff, A. (2006). Large linguistically-processed web corpora for multiple languages. In EACL’06: Proceedings of the Eleventh Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Posters & Demonstrations; 2006 Apr 5-6; Trento, Italy. Stroudsburg (PA): Association for Computational Linguistics; 2006. p. 87-90. ACL (Association for Computational Linguistics).

Bergh, G. (2005). Min(d)ing English language data on the web: What can Google tell us. ICAME journal, 29, 25-46.

Blache, P., Bertrand, R., & Ferré, G. (2008). Creating and exploiting multimodal annotated corpora. In LREC08-Language Resource and Evaluation COnference (pp. 1-5). ELDA.

Callies, M., & Götz, S. (2015). Learner corpora in language testing and assessment: Prospects and challenges. Learner corpora in language testing and assessment, 1-9.

Chahine, I. K., & Uetova, E. (2023). Spelling Issues: What Learner Corpora Can Reveal About L2 Orthography. Corpus, (24).

Cavaglia, G., & Kilgarriff, A. (2001, January). Corpora from the Web. In Fourth Annual CLUCK Colloquium, Sheffield, UK.

Crystal D. (2004). Language and the Internet, Cambridge University Press.

Ferraresi, A. (2009). Google and beyond: web-as-corpus methodologies for translators. Tradumàtica, (7), pp. 1-8.

Fletcher, W. H. (2004). Making the web more useful as a source for linguistic corpora. In Applied corpus linguistics (pp. 191-205). Brill.

Galjamina, J. E. (2014). Lingvisticheskij analiz heshtegov Tvittera. Sovremennyj russkij jazyk v internete, 13-23.

Gatto M. (2009). From Body to Web. An Introduction to the web as corpus, University of Bari.

Gatto M. (2014). Web as corpus. Theory and practice, A&C Black.

Granger, S. (2009). The contribution of learner corpora to second language acquisition and foreign language teaching. Corpora and language teaching, 33, 13-32.

Gunraj, D. N., Drumm-Hewitt, A. M., Dashow, E. M., Upadhyay, S. S. N., & Klin, C. M. (2016). Texting insincerely: The role of the period in text messaging. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 1067-1075.

Henzinger, M., & Lawrence, S. (2004). Extracting knowledge from the world wide web. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(suppl_1), 5186-5191.

Hundt, M., Nesselhauf, N., & Biewer, C. (2007). Corpus linguistics and the web. In Corpus linguistics and the web (pp. 1-5). Brill.

Irgizova, K. V. (2019). Korpusnaya lingvistika v otechestvennom i zarubezhnom yazykoznanii na sovremennom etape [Current state of russian and international corpus linguistics]. Ogarev-online, 6(127), 1-9.

Jakubíček, M., Kilgarriff, A., Kovář, V., Rychlý, P., & Suchomel, V. (2013). The TenTen corpus family. In 7th international corpus linguistics conference CL (pp. 125-127). Lancaster University.

Jaworska, S., & Ryan, K. (2018). Gender and the language of pain in chronic and terminal illness: a corpus-based discourse analysis of patients’ narratives. Social Science & Medicine, 215, 107-114.

Johannessen, J. B., & Guevara, E. R. (2011, May). What kind of corpus is a web corpus?. In Proceedings of the 18th Nordic Conference of Computational Linguistics (NODALIDA 2011) (pp. 122-129).

Johansson, S. (2014). Reflections on corpora and their uses in cross-linguistic research. In Corpora in translator education (pp. 135-144). Routledge.

Kilgarriff, A. (2007). Last words: Googleology is bad science. Computational linguistics, 33(1), 147-151.

Kilgarriff, A., & Grefenstette, G. (2003). Introduction to the special issue on the web as corpus. Computational linguistics, 29(3), 333-347.

Kovalev, V. (2014). Russo: dizionario russo italiano, italiano russo. Zanichelli.

Lew, R. (2009). The web as corpus versus traditional corpora: Their relative utility for linguists and language learners. In Contemporary Corpus Linguistics (pp. 289-300). Continuum.

Lyakso, E., Frolova, O., Dmitrieva, E., Grigorev, A., Kaya, H., Salah, A. A., & Karpov, A. (2015). EmoChildRu: emotional child Russian speech corpus. In Speech and Computer: 17th International Conference, SPECOM 2015, Athens, Greece, September 20-24, 2015, Proceedings 17 (pp. 144-152). Springer International Publishing.

Longo F. (2021). Linguistica dei corpora e corpora linguistici: analisi teorica e indagine pratica per lo studio della lingua russa contemporanea di Internet [MA thesis – Unpublished]. University of Ca’ Foscari, Venice.

Link:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365184776_Linguistica_dei_corpora_e_corpora_linguistici_analisi_teorica_e_indagine_pratica_per_lo_studio_della_lingua_russa_contemporanea_di_Internet_Korpusnaa_lingvistika_i_lingvisticeskie_korpusy_teoreticeski

Lüdeling, A., Evert, S., & Baroni, M. (2007). Using web data for linguistic purposes. In Corpus linguistics and the Web (pp. 7-24). Brill.

Lukashevich, N., Klyshinky, E., & Kobozeva, I. (2016). Lexical research in Russian: are modern corpora flexible enough. In Computational Linguistics and Intellectual Technologies: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference “Dialog”(2016)[Komp’iuternaia Lingvistika i Intellektual’nye Tekhnologii: Po materialam ezhegodnoi Mezhdunarodnoi Konferentsii “Dialog”(2016)], Moscow (pp. 385-397).

Martynjuk O. A. (2013). Korpusnaja lingvistika i novye vozmožnosti lingvističeskogo issledovanija. In Naukovyj visnik mižnarodnogo gumanitarnogo universitetu, 7, 27-33.

McEnery, T., Brezina, V., Gablasova, D., & Banerjee, J. (2019). Corpus linguistics, learner corpora, and SLA: Employing technology to analyze language use. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 39, 74-92.

McEnery, T., & Hardie, A. (2011). Corpus linguistics: Method, theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Moneglia, M., & Panunzi, A. (2010). Bootstrapping information from corpora in a cross-linguistic perspective. Firenze University Press.

Paracchini, L. (2017). La lingua di Internet in Russia: stato della ricerca. L’analisi linguistica e letteraria, 25(1), 45-98.

Paracchini, L. (2019). I meccanismi di suffissazione relativi alla formazione dei verbi nella lingua russa di Internet. Krapova I., Nistratova S., Ruvoletto L.(eds.) Studi di linguistica slava. Nuove prospettive e metodologie di ricerca” Studi e ricerche”, (20), 389.

Rozental’ D. E. (2010). Russkij Jazyk. Učebnoe posobie dlja škol’nikov staršich klassov i postupajušich v vuzy, Mosca, Oniks – Mir i obrazovanie.

Rundell, M. (2008). The corpus revolution revisited. English Today, 24(1), 23-27.

Stefanowitsch, A. (2020). Corpus linguistics: A guide to the methodology. Language Science Press.

Tavosanis, M. (2019). Variazione linguistica nei commenti su Facebook. Italiano LinguaDue, 11(1), 112-125.

Tono, Y. (2003). Learner corpora: design, development and applications. In Proceedings of the Corpus Linguistics 2003 conference (pp. 800-809). Lancaster: Lancaster University.

Volk, M. (2002). Using the web as corpus for linguistic research, in Tähendusepüüdja. Catcher of the Meaning. A Festschrift for Professor Haldur Õim, a cura di Pajusalu R., Hennoste T., University of Tartu, 355-369.

Zakharov, V. (2013). Corpora of the Russian language. In Text, Speech, and Dialogue: 16th International Conference, TSD 2013, Pilsen, Czech Republic, September 1-5, 2013. Proceedings 16 (pp. 1-13). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

[1] The website of the RLC: http://web-corpora.net/RLC/.

[2] The website of CoRST: http://web-corpora.net/learner_corpus.

[3] The website of RULEC: http://www.web-corpora.net/RLC/rulec.

[4] The website of the RSL: http://rsl.nstu.ru/site/index/language/en.

[5] Vikislovar’ is a multi-lingual dictionary and thesaurus, which was opened in 2004. Nowadays it contains 1.2 billion entries in over 600 languages. Link: https://ru.wiktionary.org/wiki.

[6] Academic.ru is a website that collects encyclopedias and dictionaries related to specific fields, such as economics, technology, computer science, biology, sociology, etc. Link: https://academic.ru/.

[7] The official website of NKRJa: https://ruscorpora.ru/.

[8] “The slang of young people 2021”, “Youth slang 2021”, “Russian young jargon”, “Russian jargon of young people”, “Trendy words 2021”, “The most popular words of 2021”.