7 The Gendered Aspect of Sociolinguistic Variation: Insights from the Qaf in Tartus, Syria

Tamam Mohamad

Department of Arabic Translation, Uzbekistan State University of World Languages, Tashkent 100173, Uzbekistan

tamamxmohamad@gmail.com

The current work is part of a larger research project investigating language variation and change within the framework of variationist sociolinguistics. The study focuses on the salient Qaf variable, realized as [q] and [ʔ] in Tartus City, Syria. The distribution and gendered evaluations of these variants are gleaned from interactions with 122 participants who belong to different gender, age, and religious/sectarian groups in the urban and rural regions of the city. The results of the logistic regression test reveal the significance of gender in the urban region, with a tendency among females to use the [ʔ] variant. In rural areas, however, gender emerged as statistically insignificant. The comments’ analysis further highlights the gendered associations of both variants and the ability of speakers to draw on them to forward specific identities. They further highlight the role of social actors and spaces in the acquisition of sociolinguistic variation and the spread of gendered evaluations among speakers since the early stages.

Keywords: language variation, Sociolinguistics, Sociophonetics, gender, Syrian Arabic, Tartus.

- Introduction

The relationship between gender and linguistic variation and change has been established since the early days of variationist studies (Cheshire & Gardner-Chloros, 1998; Labov, 1966; Trudgill, 1974, among others). The statistical significance of gender as a social variable in such studies highlights its role in “determining the structure of variation” and the “trajectory of language change” (Al-Wer et al., 2022: 55). The tendency among females to adopt prestigious and supra-local forms and their leading role in adopting new and innovative forms are two general principles formulated by Labov (1994), which were common findings in research related to gender and language variation and change in the non-Arabic world.

1.1 The Arabic context

Similar findings have been reported in the Arabic context, where women led the change and showed a tendency towards using supra-local variants (Abdel-Jawad, 1981; Al-Wer, 2007; Al-Wer & Herin, 2011; Cotter, 2016; Haeri, 1997, among others).

In Amman, the capital of Jordan, for example, Al-Wer & Herin (2011) investigate the variable usage of Qaf[1], which is realized as a voiceless glottal stop [ʔ] and a voiced velar plosive [g]. The study shows the various gendered patterns across the three generations examined, with the third generation representing the youngest age group. As for the first generation, men and women showed higher tendencies towards maintaining their original variants, exemplifying a direct correlation between their regional and ethnic usage of the (q) variants. However, Palestinian men and Jordanian women in this group showed some instances of [g] and [ʔ], respectively. In the second generation, the divergence between Palestinian men towards [g] and Jordanian women towards [ʔ] considerably increased, which led to a conflict or dilemma mainly among Palestinian men and Jordanian women in connection with their ethnic background and their gendered-linguistic behavior. In other words, for both Palestinian men and Jordanian women, ethnicity points in one direction (which is [ʔ] for the former and [g] for the latter), but gender directs in the opposite direction (which is [g] for the former and [ʔ] for the latter). As for third-generation speakers, things get complicated as females, regardless of their ethnic or regional background, started to use the [ʔ] variant consistently. However, for males of both origins, the linguistic usage varied significantly from their female counterparts as their interactions were more complex and involved ethnic background, gender, and context. These males tend to use their heritage or original variants in contexts of in-group interactions. They show the tendency to use the [g] variant in interactions involving ethnically mixed speakers. However, they would use the [ʔ] variant while speaking with girls individually or in groups.

Similar gendered patterns are reported among the younger generation of people of the Ghamdi tribe who started to migrate from Al-Baha city of Al-Hejaz region in Saudi Arabia to Mecca some hundred years ago and whose migration increased in the 70s of the last century. Such movement brought them into contact with the Meccan people, and they currently form “an essential part of the Meccan social fabric”(Al-Ghamdi, 2019: 211). The variation was analyzed in relation to the diphthongs of [ai] and [au] in the rural Ghamdi dialect, which are realized as monophthongs (i.e., [ɛː] and [ɔː]) in the urban Meccan dialect. The age groups analyzed were (14-29), (30-45), (46-61), and (62+). The gendered-generational differences in the community of the Ghamdis in Mecca emerged from the various experiences that the different groups underwent. As for the 62+ group, men moved without their families; their extended stays in Mecca and infrequent visits to their hometown resulted in adopting the Meccan variants more than females of the same generation. As for the 46-61 group, their relocation to Mecca with families resulted in different linguistic experiences; they developed a positive attitude towards the new city, culture, and the host community’s local dialect; this resulted in an increased higher level of usage of the Meccan variants. Women, however, showed lesser usage rates of these variants, which has been attributed to the socialization pattern. While men extended their networks with the members of the host community, women stayed at home and showed a tendency towards socializing with people of the original community and other migrant groups, especially those from Yemen. In the younger age group (30-45 & 14-29), women showed a higher rate of the urban variants, and men showed a decrease of 17% percent. This behavior on the part of the younger generation, especially men, has been attributed to the positive attitude and pride they showed toward their heritage dialect, reflecting a more secure position in the host community compared to the older generation group. Thus, the females’ lead in using the Meccan variants is not different from other communities in the Arab world and other languages as well.

In a study of the variable /ʤ/ and its two variants [ʤ] and [ʒ] in Medina, Abeer Hussain (2017, cited in Al-Wer et al., 2022: 56–57) shows women’s linguistic behavior was characterized by convergence towards the incoming supralocal and prestigious [ʒ] form, that is characteristic of the dialect of Jeddah. Moreover, though she reports higher usage of the [ʒ] variant among middle and old-aged male groups, the younger female groups used the [ʒ] at higher rates than their age group counterparts.

Abu Ain’s (2016) study in the Jordanian village of Saḥam reports gender and age as statistically significant, as well. The two features investigated are the traditional features of [u] and [ɫ], which alternate with the supralocal features of [i] and [l], respectively. The village is characterized by its proximity to the urban center of Irbid. The increasing connectivity with the city of Irbid through a new road and public transport has transformed the village’s linguistic situation. It increased the access of the younger generation, who regularly commute for work and studies. The results reveal age and gender as statistically significant, where the younger generation and mainly females show a higher tendency towards the supralocal variants. The two variants showed different abandonment rates, with the [ɫ] variant being more abandoned than the [u] one due to its high stigmatization outside the region, which is not uncommon in the context of variation and change. This can be led by linguistic or social factors. In this context, for example, the young females’ divergence from the traditional dialect can be regarded “as symbolic of their aspirations for social change” (Al-Wer et al., 2022: 61).

These dynamics are context-specific, and the various gender roles, practices, and expectations in a society can determine the leaders of such change. In the city of Sūf, in Jordan, Al-Hawamdeh’s (2016) study reveals an ongoing change led by men from the localized [iʧ], [ʧ], and [ɫ] to the supralocal [ik], [k], and l], respectively. Unlike men, women’s speech is characterized by “a stronger Hōrāni ‘flavor’” (Al-Hawamdeh, 2016: 172). She explains this by highlighting the gender roles of men and women. On the one hand, “many of the men are daily commuters to nearby cities” of Irbid and Amman (Al-Hawamdeh, 2016: 172). This allows them to establish broader and richer social networks than their counterparts. Women, on the other hand, are locally employed, and their social contacts are locally oriented. They are expected to maintain the local culture, and one of the ways is by preserving the local linguistic features. They “spend most of their time in the town, interacting with local people and caring for the family” (Al-Hawamdeh, 2016: 172).

It is well established in the literature that the usage of certain features interacts with the social indices that such features acquire in regional or national contexts. The indices or evaluations of these variants that may develop can act as competing factors and complicate speakers’ linguistic choices in various contexts. The diverse and sometimes contradictory associations or indices that dialects or features of dialects acquire can intensify the sociolinguistic dilemma for their speakers. In this respect, an urban dialect, or the [ʔ] variant, can be associated with “modernity” but be seen as inappropriate for males. A rural dialect, or [q], on the other hand, can be “stigmatized” but be associated with “local culture,” “masculinity,” “strongness,” “toughness,” and “power” (Habib, 2016). Furthermore, such evaluations may vary among the groups present in the larger society. A prestigious variant on the national level can be downplayed in different rural settings where other variants would be more socially meaningful and hold positive associations.

1.1.1 Gendered associations

The gendered associations are such ones that are ideological and primarily based on the context and the nature of the groups involved. In Jordan, Al-Wer & Herin (2011) highlight this ideological construction and connect such associations to the increased usage of one variant by one group of speakers, which would gradually be associated with them. They contend that “[a]s women increasingly adopted the glottal stop pronunciation of Qaf, this sound became associated with women’s speech. It is not that the sound is intrinsically ‘softer’ or ‘feminine,’ as one often reads in the literature regarding this variant of Qaf, but the fact that it is used more frequently by women is what gave rise to this association” (Al-Wer & Herin, 2011: 70-72).

These associations, positive or negative, can eventually influence the long-term and short-term linguistic choices of speakers. The degree of stigmatization of certain variants in specific contexts, for example, can affect the speed of abandoning certain stigmatized linguistic variants and the adoption of their supralocal counterparts, especially by those who wish to be associated with different dialectal backgrounds. The younger generations, especially females, can lead such aspirations. In Jordan, Abu Ain’s (2016, cited in Al-Wer et al., 2022: 60–61) analysis shows that the [ɫ] variant was more stigmatized out of the rural region thus, was more readily subject to abandonment. However, Abu Ain’s results reveal a high tendency towards embracing the [l] variant by both genders, with women showing higher rates, which she explains by their will for social change.

1.2 Previous studies in the Syrian context

Research conducted in a few Arabic cities has revealed the presence of such gendered tendencies and evaluations, which set the [q] and [ʔ] in contrast (Daher, 1998; Habib, 2005, 2010, 2016). In Habib (2010), for example, the results of the quantitative analysis showed the tendency among women towards the [ʔ] variant compared to men who tended to use the rural variant [q]. Daher (1998) examined the Qaf variable in Damascus by focusing on the colloquial [ʔ] and the Standard [q]. The study was conducted on a balanced sample of twenty-three men and an equal number of women, classified into three age groups, namely (15-24), (25-39), and (40-70). The level of formal education was a main factor and the sample was classified into elementary, high school, and degree level. Daher argues that the [q] variant in Damascus has been mainly reintroduced through education. He also contends that the [q] is the norm for a minority of speakers, and he probably speaks of migrants of rural origins, who still maintain their original dialectal features. He found gendered-based differentiation between men and women in relation to the usage and associations of the variants. On the one hand, women, even the professional and educated ones, showed a tendency towards using the [ʔ] that is associated with urbanization and modernity. On the other hand, men tended to use the [q] variant which is associated with men norms and rurality. This differentiation is mainly due to the different norms that men and women approach. For him, the [q] was introduced to the dialect through education. Furthermore, the tendency of men towards the [q] is due to its association with education which was “traditionally the domain of a small male elite” (Daher, 1998: 203).

1.3 The aim of the research

In line with what has been discussed, this study aims to examine the distribution of the [q] and [ʔ] variants among males and females in the urban and rural regions of Tartus City, Syria. It also intends to examine the emergence and development of gendered indices or associations of these variants and speakers’ ability to employ them in real-life situations. Moreover, the study further aims to highlight the role of various social factors and spaces in the acquisition of such gendered evaluations.

2. Data collection

Data for this research was collected during the fieldwork period at Tartus City, which lasted from July 2019 until September of the same year. The investigation focuses on the realization of the (q) variable in the context of Tartus. It makes use of interactions with 122 participants from various backgrounds in the urban and rural regions of Tartus. For this study, comments have been further analyzed as a tool for explanation.

Participants ranged between the urban and rural regions. While 93 were from the urban areas, 29 were from the rural ones (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of Participants Across Urban and Rural Regions.

| Gender | No. of participants | Percentage |

| Urban | 93 | 76.2% |

| Rural | 29 | 23.8% |

| Total | 122 | 100.0 % |

The sample has been divided into five age groups: (19 and below), (between 20-29), (between 30-39), (between 40-49), and (50 and above). The number of participants in each age group is 21, 32, 28, 14, and 27, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of Participants Across Age Groups.

| Age group | No. of participants | Percentage |

| 19 and below | 21 | 17.2 % |

| Between 20-29 | 32 | 36.2 % |

| Between 30-39 | 28 | 23.0 % |

| Between 40-49 | 14 | 11.5 % |

| 50 and above | 27 | 22.1 % |

| Total | 122 | 100.0 % |

Classifying people into their biological gender was not an issue for all participants in the study. The sample included 73 males and 49 females (Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of Participants Across Gender Groups.

| Gender | No. of respondents | Percentage |

| Males | 73 | 59.8% |

| Female | 49 | 40.8% |

| Total | 122 | 100.0 % |

Speakers’ religious/sectarian affiliation is a sensitive issue in the Syrian context, especially in public contexts. However, all the participants agreed to say their religious background and those who did not were not included or recorded. The sample included 94 Muslim Alawites, 15 Christians, and 13 Muslim Sunnis (Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of Participants Across Religious/Sectarian Groups.

| Religious/Sectarian groups | No. of participants | Percentage |

| Muslim Alawites | 94 | 77.0% |

| Christians | 15 | 12.3% |

| Muslim Sunnis | 13 | 10.7 % |

| Total | 122 | 100.0 % |

2.1 The target variable

The variable for this study is the Qaf which is a salient feature in Arabic dialects (Al-Wer & Herin, 2011, p. 50) and has been in focus in dozens of studies in the Arabic context (Abdel-Jawad 1981; Al-Khatib 1988; Daher 1998; Suleiman 2004; Habib 2005, 2010, 2011, 2016). The main reflexes of the Qaf in the context of Tartus City are the [q] and [ʔ] or the [qaf] and [ʔaf], respectively. While the first is a voiceless uvular plosive, also used in Standard Arabic (Al-Khatib 1988, p. 80), the second is a voiceless glottal stop.

Previous studies in the Arabic context (Abdel-Jawad, 1981; Al-Khatib, 1988; Al-Wer, 2007; Al-Wer & Herin, 2011; Daher, 1998; Habib, 2005, 2010, 2016, among others) have shown that the (q) variable is externally and not internally motivated. In other words, the phonological context (be it initial, internal, or final) of the variable does not determine its realization as [q] or [ʔ]. Words like /[ʔ]ələm/ “pen”, /bə[ʔ]lawa/ “sweets”, and /sibӕ:[ʔ]/ “race” can be realized as /[q]ələm/, /bə[q]lawa/, and /sibӕ:[q]/, respectively by an [ʔ] speaker.

3. Data analysis

3.1 Quantitative analysis of interactions

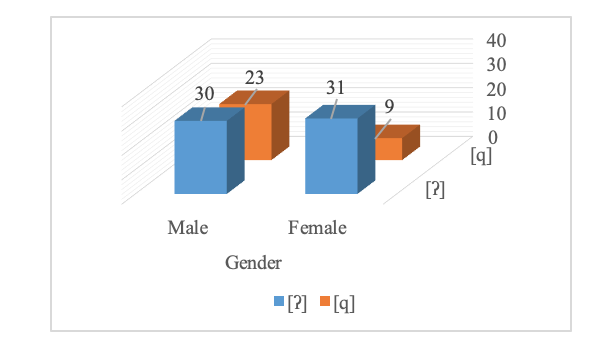

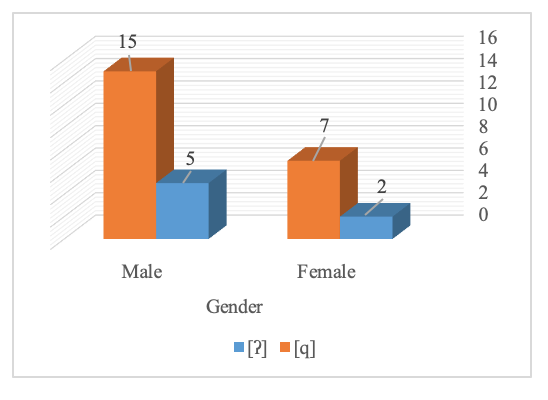

As the analysis requires the categorization of participants into [q] and [ʔ] speakers, this was done based on the actual occurrences of [q] and [ʔ] in both the urban and rural regions. While Table 5 shows the number and percentages of [q] and [ʔ] speakers in the whole sample, Charts 1 and 2 show the tabulation of speakers according to their [q] and [ʔ] in the urban and rural regions.

Table 5. Distribution of [q] and [ʔ] in the Whole Sample.

| (q) | No. of respondents | Percentage |

| [ʔ] | 68 | 55.7% |

| [q] | 54 | 44.3 % |

| Total | 122 | 4.0 % |

Chart 1. (q) * Gender Crosstabulation: Whole Sample – Urban Region.

Chart 2. (q) * Gender Crosstabulation: Whole Sample – Rural Region.

This research was analyzed through the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, 26.0). Following previous research (Speelman, 2014, p. 487; Tagliamonte, 2016, pp. 113-114), the Binomial Logistic Regression Test was used for analyzing the existing variation as the variable is a binary one.

3.1.1 Quantitative analysis and results

In this section, we checked the role of gender in the realization of Qaf’s variants. As noted earlier, this is part of a larger research that includes other variables. We are focusing here on gender but referring to other variables and their results in their context. The hypotheses are as follows:

Null hypotheses: There is no statistically significant correlation between the factor of gender and the realization of (q) in the urban and rural regions.

Alternative hypotheses: There is a statistically significant correlation between the factor of gender and the realization of (q) in the urban and rural regions.

The results (see Table 6) show that the factor gender is statistically significant and, specifically, the category coded as 1 (i.e., F) where the sig. value is 0.009, which is less than 0.05, with B (-1.826) and Exp(B) as (.161). This makes us reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative one that says, “there is a statistically significant correlation between gender and the realization of (q) in the urban region.”

Table 6. The Urban Sample: Variables in the Equation.

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | |

| Age | 12.223 | 4 | .016 | |||

| Age(1) | -2.637 | 1.019 | 6.697 | 1 | .010 | .072 |

| Age(2) | -2.461 | .937 | 6.899 | 1 | .009 | .085 |

| Age(3) | -.989 | .961 | 1.059 | 1 | .303 | .372 |

| Age(4) | -.242 | 1.415 | .029 | 1 | .864 | .785 |

| Gender(1) | -1.826 | .699 | 6.824 | 1 | .009 | .161 |

| Religion/Sect | .000 | 2 | 1.000 | |||

| Religion/Sect(1) | .073 | 15668.113 | .000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.076 |

| Religion/Sect(2) | -20.277 | 10328.888 | .000 | 1 | .998 | 5467066280.415 |

| Constant | -20.277 | 10328.888 | .000 | 1 | .998 | .000 |

a Variable(s) entered on step 1: Age, Gender, Religion/Sect

However, in the rural regions, gender emerged as insignificant, with a sig. value higher than 0.05. This makes us accept the null hypothesis that says “there is no statistically significant effect of the factor of gender on the realization of (q) in the rural region.”

Table 7. The Rural Sample: Variables in the Equation.

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | ||

| Age | .000 | 4 | 1.000 | ||||

| Age(1) | -.184- | 26116.681 | .000 | 1 | 1.000 | .832 | |

| Age(2) | -20.761- | 12802.494 | .000 | 1 | .999 | .000 | |

| Age(3) | .308 | 20704.375 | .000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.360 | |

| Age(4) | 19.118 | 20046.775 | .000 | 1 | .999 | 200936588.473 | |

| Gender(1) | 1.099 | 1.826 | .362 | 1 | .547 | 3.000 | |

| Religion/Sect | .000 | 2 | 1.000 | ||||

| Religion/Sect(1) | 1.391 | 44914.888 | .000 | 1 | 1.000 | 4.020 | |

| Religion/Sect(2) | 41.964 | 42182.671 | .000 | 1 | .999 | 1676955638519 | |

| Constant | -21.203- | 40192.959 | .000 | 1 | 1.000 | .000 | |

a Variable(s) entered on step 1: Age, Gender, Religion/Sect

3.1 Qualitative analysis of the comments in the interactions

Following previous research in the Arabic context, which partially or wholly adopted the qualitative analysis of variation and change, we provide a qualitative analysis to highlight the patterns of speakers’ choices between [q] and [ʔ] variants in specific contexts and to uncover the social meanings and attitudes that these variants carry for participants, the possible groups they are part of, and the society at large.

For this, the current research relies on comments or “talks about language” (Bassiouney, 2017a, p. 7) that emerged from participants’ comments regarding the usage and preferences of one variant rather than another. These comments have been used by previous research in the Arabic context (Bassiouney, 2017a, 2017b, 2018; Habib, 2016; Hachimi, 2007) as they play a role in highlighting the psychological motivations for the linguistic differences and linguistic choices that speakers make (Llamas, 2007: 581). They have largely been shown to support and complement the statistical analysis. These comments further highlighted the actual reasons for why, how, and when speakers employ linguistic variation regarding [q] and [ʔ] and the various as well as different indices associated with them in forging identities. Such analysis highlights how speakers’ identities can change at certain stages of their lives.

It should be noted that I include only those comments pertinent to the themes and questions raised in this research. Moreover, those comments about the same linguistic issues were not included. As the interest in these comments was mainly in the content rather than the style, these excerpts were only translated, and the transcribed versions were not included. For this, turns, repetitive elements, laughter, etc., which I considered irrelevant to the discussion, have been omitted. These deleted items are substituted with three dots. Details about the participants and respondents were presented at the top of the excerpt, including the demographic information available. Whenever needed, the flow of the details was included, along with the possible questions or notes I was making during the interactions. The comments that emerged from the questionnaire were one-sided and directed at me.

Any needed explanations or gaps between phrases, sentences, or paragraphs that speakers may have assumed to be understood and not said have been inserted within square brackets to clarify what is needed if assumed unclear by me.

4. Discussion

The current research findings lend support to previous research in the non-Arabic and Arabic contexts. The data examined shows gender as statistically significant in the urban region but not in the rural ones. Female speakers in the urban regions show higher tendencies toward the [ʔ] variant compared to their male counterparts who tend to use the [q].

These tendencies highly reflect the gendered ideologies that are dominant in such regions, where it becomes “more appropriate” for females to use the urban forms (i.e., [ʔ]) and for males to use the local forms (i.e., [q]) (Habib, 2016). Unlike males who show a tendency to identify with local linguistic norms and practices and, in this case, the [q] variant, females “are more sensitive to social norms and thus linguistic norms in their environment” (Labov, 1972: 303, cited in Habib, 2010: 86).

The urban and rural disparity regarding the gendered distribution and evaluation of the Qaf variants in the population examined is, to some degree, influenced by the sociopolitical and religious dynamics in this context. Until the mid-1950s, less contact was established between the urban and rural populations of the city, where Alawites constituted the majority in the rural regions compared to the urban ones, which Sunni and Christian people dominated. The social and political changes in the Syrian context – which started in the early 20th century – brought waves of rural migrants (mainly Alawites) into the urban regions. This eventually altered the religious-sectarian distribution in the urban center marking Alawites as the majority in urban and rural areas (Balanche 2015: 88, 2018: 6; Khaddour 2015). These waves of migration did bring the population together geographically but not socially. New localities emerged but were dominated by the rural population. Furthermore, people of rural origins showed a tendency to maintain their rural links within the city and between the urban and rural regions, with many of the rural population commuting daily to the city for government jobs. Consequently, less contact marked the earlier and, to some degree, the later stages of migration. The following decades brought changes to these dynamics with the emergence of more mixed spaces for interaction between the various components.

Thus, the [q], which is dominant among the rural population (which is largely Alawites) in Tartus, migrated to the city and got closer to the [ʔ] of the urban center. However, the lack of contact for decades contributed to the relative maintenance of religious/sect-based linguistic distribution, where the [q] remains dominant among Alawites, and [ʔ] being dominant among Sunni, Christians, and relatively increasing among Alawites (Mohamad, 2023). Despite this maintenance, there has been a slow change in progress among the population examined, with the younger age groups (39 and below) showing a tendency towards using the [ʔ] variant, compared to the older ones (Mohamad, 2022).

On the evaluation side, it was not uncommon in the urban region to describe males of rural backgrounds who speak with [ʔ] as feminine, mainly by people of the same background who are [q] speakers. The [q] has been largely associated with masculinity, and the [ʔ] with femininity in the context of Tartus City.

The gendered-linguistic distribution reflects the socially constructed nature of masculine and feminine associations concerning the [q] and [ʔ], which are still in action among speakers of rural origins, despite the said ongoing pace of change. Such gendered differentiation largely aligns with previous studies in the Arabic and Syrian contexts (Abdel-Jawad, 1981, 1987; Al-Khatib, 1988; Al-Wer, 2007; Al-Wer & Herin, 2011; Daher, 1998; Habib, 2005, 2010, 2016).

The gendered associations that dialects or features of dialects may develop act as competing factors and add to the sociolinguistic dilemma that such speakers face in various contexts. All these gendered associations are ideological and are primarily based on context and the nature of the groups involved. As discussed before (Al-Wer & Herin, 2011, pp. 70-72), the claimed association of the [ʔ] in Jordan with “softness” and “femininity” could have resulted from it being increasingly and widely adopted by women. The gendered construction of such associations is evident in other contexts. In Algeria, for example, Dendane (2013) shows how the [ʔ] is being stigmatized in the city of Tlemcen, which is gradually leading native speakers, especially young males, to avoid using it under the pressure of the [q] and [g] variants, which are more common in other cities in Algeria. However, he shows that females still retain the [ʔ] variant. Thus, an association between the [ʔ] and feminine speech can emerge as women continue to maintain and use it compared to their male counterparts.

Examining the views of sub-groups may reveal various patterns within the sample. Christians, for example, are dominantly [ʔ] speakers, and in this respect, the masculinity-femininity distinction related to the (q) variable is likely to be absent from them. Moreover, such gendered differentiation is less likely to be dominant in rural regions where males and females are mainly [q] speakers. We believe that these gendered evaluations are more common among migrant groups who are originally [q] speakers and who got in contact with [ʔ] speakers. For such groups, it is not uncommon for men and women to avoid gendered linguistic features associated with the other gender to confirm their distinct gendered identity. For Coates (2003: 69), “[o]ne significant way in which hegemonic masculinity is created and maintained is through the denial of femininity. The denial of the feminine is central to masculine gender identity,” which “means that men in conversation avoid ways of talking that might be associated with femininity and also actively construct women and gay men as the despised other. Hegemonic masculine discourses are both misogynistic and homophobic.” In Morocco, for example, Hachimi (2012) reports that men in Casablanca avoided the usage of the Fessi approximant [ɹ] as it is likely to show them as “effeminate.” Non-Fessi women reportedly used the same features to project and exaggerate their femininity. In the Syrian context, Habib (2016) found that male adolescents in the village of Al-Oyoun tended to avoid the [ʔ] as it is likely to project them as “effeminate,” “soft,” etc. Similarly, females were resorting to embracing such features as using [q] is associated with being “tough,” “masculine,” etc. Habib showed that gendered ideologies are common among boys, girls, and parents.

4.1 The gendered associations in Tartus

These gendered ideologies have been reported among speakers of rural origins in the city of Tartus, who still maintain and forward such gendered differentiation regarding the appropriateness of [ʔ] for females and the [q] for males, which largely affect their linguistic behavior.

In Excerpt (1), the female speaker, who is a Muslim Alawite from the city, contends that the [ʔ] is more admirable for females and the [q] is nicer among males, and that is why she encourages her brother to speak with [q] because it is not nice for a male to speak with [ʔ].

Excerpt 1. Speaker 46: 17, Muslim Alawite, Female, Urban, [ʔ].

| Interviewer: Do you generally speak with ʔaf or qaf?

Participant: With ʔaf. Interviewer: And dad? Participant: My dad speaks with qaf. Interviewer: And mom? Participant: qaf. Interviewer: Why do you speak with ʔaf then? Participant: They taught us to speak with ʔaf, especially mom. Sometimes, we use the qaf when we are with a group of qaf speakers. Interviewer: If you go village, what do you use? Participant: It depends! Interviewer: What about your brothers? Participant: My youngest brother is in the 7th grade now. Interviewer: He speaks with ʔaf also, right? Participant: No, with qaf. He is a guy. I tell him it is not nice for a guy to speak with ʔaf, which makes him speak with qaf. Interviewer: Why? Participant: I don’t know! Interviewer: Your mom does not tell him to speak with ʔaf? Participant: No, because it is nicer for a girl to speak with ʔaf, but not for guys. |

Since childhood, these gendered-differentiated ideologies, attitudes, and practices are widely spread and commented on.

The role of both parents (largely mothers) on this gendered differentiation and the linguistic practice of their children, with moms usually pushing towards [ʔ] and fathers being inattentive or otherwise pushing towards [q]. As we saw in Excerpt 1 above, both parents are [q] speakers, but the mother encourages the daughter to speak with [ʔ].

In Excerpt 2, the speaker is a male Muslim Alawite of rural origins residing in the city. He highlights his desire to make his young son speak with [q] and not with [ʔ]. He says that his son is still a child, and it may be difficult for him to speak with [q], so he does not put high pressure on him. During data collection, I interviewed his son, who was six years old (participant 15), with other speakers of his age group before we interviewed his father. In this study, the father is categorized as a [q] speaker and the son as a [ʔ] speaker (see Table 8). It should be noted that we have encountered many incidents where children below age seven are addressed with [ʔ] even when the speakers themselves are [q] speakers.

Excerpt 2. Speaker 16: 38, Muslim Alawite, Male, Urban, [q].

| Interviewer: Your son speaks with qaf or ʔaf?

Participant: No, he speaks with ʔaf. Interviewer: What do you think about that? Participant: I am not happy about this, honestly speaking. […] Participant: He should speak with qaf. But now, he is a kid, and it is probably easier for him, as qaf needs more force to be used. But in general, the qaf surrounds him from all directions.

|

Table 8. Father and Son: [q] and [ʔ] Distribution.

| Speaker | Age | Gender | Religion/Sect | Region | No. of [q] | % of [q] | No. of [ʔ] | % of [ʔ] | Total No. of [q] and [ʔ] | [q] or

[ʔ] |

|

| 15 (Son) | 6 | M | MA | U | 3 | 17 | 15 | 83 | 18 | ʔ | |

| 16 (Father) | 38 | M | MA | U | 21 | 91 | 2 | 9 | 23 | q | |

4.1.1 The role of family and school in shaping gendered-linguistic behavior

While families are the first sites where speakers may encounter such variants and variation, schools have been regarded among the early public spheres where speakers, especially [q]-speaking females, are exposed to such ideologies, which may pressure them to change their linguistic behavior. Such attitudes and pressure are largely gendered, pushing females towards [ʔ].

In Excerpt (3), the speaker describes the encounter she experienced with her sister with [ʔ]-speaking schoolmates as early as 6th grade when they shifted to the city after being brought up in a village to [q]-speaking parents. As they moved to the new school in the 12th grade, the speaker says their school friends started to mock their [q] usage. They, however, began to defend themselves, alluding to the originality of [q] and its Qur’anic associations. This defensive mechanism did not work, and they felt more pressure. After telling their mother about their experience, she asked them to begin speaking with [ʔ]. The speaker said she is an [ʔ]-speaking person, which matched our analysis. She says her brother usually speaks with [ʔ], but he tries to talk with [q] with a group of elderly male speakers.

Excerpt 3. Speaker 12: 27, Muslim Alawite, Female, Urban, [ʔ].

| Participant: At that time, our friends at school started to mock us … We started saying that the basis of Arabic is this and that this represents our Arabness and identity and is the language of the Qur’an, and such arguments … Gradually, we started to feel that we were wrong. At that point, our mom started telling us that we should speak with ʔaf.

[…] Participant: My brother speaks according to who he is sitting with. Sometimes, he sits with my father’s friends, and he starts using qaf, a heavy qaf, I mean. I feel it is heavy as I am not used to hearing him using it, and he is not used to speaking like that. Interviewer: Doesn’t he make mistakes? Participant: Yes, yes, he makes mistakes; he speaks with [q] and [ʔ]. |

4.1.2 The role of other spaces in shaping gendered-linguistic behavior

Such gendered ideologies have affected many participants, whether males or females. In Excerpt 4, the male participant, whose family migrated from the rural regions of Tartus to Damascus, describes his daunting experience after an accident where a ruler came through his mouth and prevented him from pronouncing many sounds at an earlier stage after the surgery is done to him. With experts’ supervision and medical attention, he could retrieve all sounds except the [q], where he could pronounce it only as [ʔ], even when reading an Arabic text in class. Not being able to pronounce the [q] caused him many issues at school but not within society at large. Later, shifting back to the village, he suffered more. This suffering decreased as he moved to the urban center of Tartus. However, this escalated when he went to do military service, where he had to introduce his rank, which is “first sergeant,” which translates into /rə[q]i:b/ but can be said with an [ʔ] as part of colloquial Arabic (i.e., /rə[ʔ]i:b/). This made him avoid introducing his rank and worry about the commentary of the officer-in-charge. Later, when he was told that he should present his rank and name, he introduced that as /rə[ʔ]i:b/, where the officer said: “We do not have /rə[ʔ]i:b/ in the army.” Due to various sources of pressure, he decided at a point in time to download a YouTube video of how to pronounce [q] and eventually managed to pronounce it.

Excerpt 4. Speaker 11: 30, Muslim Alawite, Male, Urban, [q].

| Speaking about his stay in Damascus:

Participant: I suffered during my study days a lot. I did not even participate in classes [because of the [q]]. […] Participant: They did not understand that I could not produce the [q].

[In village] Participant: Later, I came to the village … I suffered a lot … How can you pronounce the qaf as ʔaf? You are a man! […]

[In Tartus] Participant: I suffered here also, but the society here in Tartus City showed more acceptance of this. |

The pressure towards [ʔ] is not directed to females alone, as other males in the urban regions have been undergoing such pressure, but with lesser reported cases in our observation. In such situations, the urban factor and indices seem to compete with and override the gender-specific categorization dominant in society. Such sociolinguistic pressure largely falls in line with the patterns of intra-speaker variation found among males who appear to accommodate the various identities they want to forward according to different contexts. In Excerpt 5, the speaker was the only one who described himself as a [q] and an [ʔ] speaker, though he assured that he is considered an [ʔ] speaker. He highlighted the identity struggle between the two variants and their associations. The first is toward the urban [ʔ] that his mom and other urbanites speak with. The second is the [q] that his dad and other ruralites use. He is a relative of speaker 16, who also commented that the child’s mother tends to direct her children to speak with [ʔ].

Excerpt 5. Speaker 58: 11, Muslim Alawite, Male, Urban, [ʔ].

| Interviewer: Do you say /[q]alʕa/ or /[ʔ]alʕa/ (= castle)?

Participant: I say /[ʔ]alʕa/. My mom wants me to get used to this. I used to say /[q]alʕa]/, like my dad. Interviewer: All of your mom’s speech is ʔaf? Participant: [ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ …] Interviewer: And your dad? Participant: [q, q, q, q, q, q, q, q …] and I am [q, ʔ, q, ʔ, q, ʔ, q, ʔ…]. Interviewer: Do you have a sister? Participant: Yes, [ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ]. Interviewer: Why do you speak like this then? Participant: The boy wants to be like his father, and the girl wants to be like a girl. I used to pronounce it as qaf …I did not know because, in my village, they pronounce the (q) as [q]. It has become a habit for me that I cannot get rid of. […] Participant: At school, I like to speak with [ʔ] so that people do not think I am [from the village] […] Interviewer: What do you use with your father? Participant: [q, q, q, q, q, q] but if my mom is present, [ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ, ʔ]. |

Table 9. Speaker 58: [q] and [ʔ] Distribution.

| Speaker | Age | Gender | Religion/Sect | Region | No. of [q] | % of [q] | No. of [ʔ] | % of [ʔ] | Total No. of [q] and [ʔ] | [q] or

[ʔ] |

|

| 58 | 11 | M | MA | U | 10 | 48 | 11 | 52 | 21 | ʔ | |

The linguistic practices of participant 58 and the intra-variation he reported, which we noticed throughout our interaction (Table 9), fall within the dilemma that speakers of rural origins in both the rural and urban regions undergo in situations of in-migration and dialectal contact. Such pressure emerges from various social reasons and partially from speakers of the same rural origins who are themselves early migrants who have already adopted the urban style of life. Despite his young age, the young boy’s linguistic behavior and comments reveal a high level of awareness of the social embeddedness of the variants in question and his ability to employ that in his speech. On the one hand, he prefers to use the [q] with his [q]-speaking dad, who became his model. It is more likely that this can lead to an association between his usage of [q] and masculinity. He is simultaneously forced to use the [ʔ] with his [ʔ]-speaking mom. His sister, he believes, should speak like girls, which means [ʔ], and this is yet a reflection of the gendered differentiation present in society. Interestingly, he preferred to use the [ʔ] in school to forward an urban identity, as using [q] may show his rural background.

Clearly, a state of complication and part of the dilemma that speakers have, as young as 11 in our case, involve the variants’ choices and the ability or the will to convey different identities, including the gendered one, through the selection of one variant rather than another.

4.1.3 Identity construction

We can assure that the young boy’s usage of [q] and [ʔ] is quite smooth, as he is very adaptable to both variants. We further believe that this case is an excellent example of how speakers can exploit the existing variation between variants (Eckert, 2005) and use the various social indices to forward one or more identities rather than others.

Such linguistic practices are largely contextual and align with the stance, role, social position, or identity he wants to associate with. In other words, it is clear that his linguistic practice is not solely dependent on the macro-level categories that he is born into. Rather, he seems to continuously employ the acquired or taught variation to forward various identities at various times, reflecting any level of identity or social group he wants to associate with or is obliged to. Such identities can vary between (1) macro-level demographic identities, (2) micro-local identities, or (3) interactional ones (Bucholtz & Hall, 2005: 592). In this respect, his usage of the [q] with his dad or with other speakers can be indicative of the gendered-masculine identity, which sets him as part of the gendered-masculine and spatial community of practice where the [q] is more appropriate for male speakers of rural origins (Habib, 2016). Though using the [ʔ] largely happens due to his mother’s influence, he willingly uses it at school to forward the urban identity. Such an “urban” index seems to override and differ from the “feminine” index in such situations. Throughout his interactions, he seems to be able to manipulate the various linguistic resources to show various stances, roles, and identities that can serve his purposes (Wolfram & Schilling, 2016: 39).

Such linguistic behavior is not uncommon among migrant speakers or speakers of rural origins whose dialects or features of dialects acquired various and, in some cases, contradictory social indices that can increase dilemmas for their speakers between “social approval,” thus fitting in their new community or talking properly according to “group solidarity.” It is not uncommon in such contexts for patterns to vary between speakers who maintain either of the variants and those who show a balanced act and flexibility between balancing the various social considerations (Wolfram & Schilling, 2016: 39). Thus, we can say that speakers employ such existing variation to forward one identity rather than another.

4.1.3.1 Short- and long-term identity construction

While in most cases, such switches represent interactional identities (temporary) that speakers may want to forward; some speakers reported significant changes across their life stages, mainly toward the urban dialects and the [ʔ] feature. At the same time, many speakers do not make such switches and show higher tendencies towards maintaining their original identity, which can signify group solidarity. Speaker 29 is a 38 years old Muslim Alawite female who resides in Al-Ghadeer locality. After the interaction (see Excerpt 6) that happened in the presence of my mom, her daughter, and a friend of hers, I asked her about her usage of [q] as she categorically used it (see Table 10). She immediately spoke about a recent incident that happened to her during a visit to Damascus, where her cousin asked her to “soften the [q] that is as big as the sofa.” She stated that she refused to do so and said that she does not feel that she belongs to the other side (i.e., [ʔ]-speaking side); she expressed her pride in the dialect and the [q] that she uses.

Excerpt 6. Speaker 29: 38, Muslim Alawite, Female, Urban, [q].

| I am going to tell you about my workplace; the percentage that I see, people who speak this, three-quarters of them speak with the [Ɂ].

[…] I could not take this side [= I could not speak with [Ɂ]]. I maintained what I am and not what I am exposed to; I am like this. My reality is this. This is the reality that represents me. I did not feel … I went to Damascus, where I visited Al-Hamidiyeh, and my cousin told me: ‘Please, soften the [q] that is as big as the sofa …enough, do not speak.’ Why would I do this, my brother? [said even to someone who is a cousin]: This is my dialect, and I am proud of it. […] We do not have the culture of being what you are. |

Table 10. Speaker 29: [q] and [ʔ] Distribution.

| Speaker | Age | Gender | Religion/Sect | Region | No. of [q] | % of [q] | No. of [ʔ] | % of [ʔ] | Total No. of [q] and [ʔ] | [q] or

[ʔ] |

|

| 29 | 38 | F | MA | U | 16 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 16 | q | |

Through such linguistic practices and the exploitation of the available associations, many speakers, especially in the urban regions, show higher adaptability towards varying their linguistic practices between the [q] and [ʔ]. Such switching indicates a large level of intentionality that individuals decide to go for depending on their context and the appropriate situation they find themselves in. Such linguistic practices and other similar ones that involve switching between the variants largely resemble the “innovative” and “complex” linguistic behavior of third-generation females and males of Jordanian and Palestinian backgrounds reported in Jordan (Al-Wer & Herin, 2011: 69). On the one hand, females seem to be largely consistent in their [ʔ]-usage with less switching, thus maintaining the “urban” image they developed. However, males show “innovative” and “complex” patterns of linguistic usage. They resort to interactional switches between their heritage background, gender, and context or interlocutor. Boys tend to use the [ʔ] variant when speaking with females and are more likely to use their heritage variant with speakers of the same ethnicity and during in-group interactions. The usage of [ʔ] by male speakers when speaking with females has been reported among boys in the village of Al-Oyoun (Habib, 2010). Such use is interactional, and in such situations, we cannot say that such male speakers are forwarding “the feminine” identity. Rather, it is an association with an urban identity that they are likely to forward.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, the quantitative analysis revealed the gendered distribution of the [q] and [ʔ] variants in the urban region, with females showing a higher tendency towards using the [ʔ] variant compared to their male counterparts. In the rural regions, however, gender was not statistically significant, with males and females showing a higher tendency towards the [q] variant.

Moreover, the analysis of comments has revealed the considerable presence of gendered associations in the urban region, with [q] being more suitable for males and [ʔ] being more appropriate for females. These associations have little space in rural areas, with males and females being largely [q] speakers.

The analysis further showed how such associations are socially constructed, exemplified in the relative absence of such gendered indices among males and females in rural regions. It shows that the dominance of one variant among a group, which is females here, can influence its associations, affecting its usage and distribution. It should be noted that gendered-evaluations still exist, but have been decreasing relatively in the past few years within the urban population of different origins, as mixing increased and as members of the same family of rural origins started to vary between the [q] and [ʔ].

The study showed that the awareness of variation could start early in life, especially with salient variables (Chevrot et al., 2000: 296; Smith & Durham, 2019: 7–8) such as the Qaf (Habib, 2016, 2017).

The family can trigger these associations and sociolinguistic competence, and the members become the first agents of such influence. This emergence is not straightforward as it may take a gendered orientation, with females being encouraged towards the [ʔ] and males towards the [q] by their mothers and fathers, respectively. Later, or simultaneously, comes the role of caregivers (Smith & Durham, 2019) and school, friends, and other social spaces, especially as speakers shift or migrate from one locality to another and from rural to urban regions.

The study underscored speakers’ agency and ability to employ the various indices in certain contexts to forward specific identities. The comments of speaker 58 and the reverse from speaking mainly with [ʔ] to speaking with [q] and [ʔ] is an example of such emergence and later development.

It has become clear that variation regarding the Qaf variants and their acquisition and development is not straightforward. Many factors – social, political, local, and supra-local factors- can shape their distribution, usage, and associations.

References

Abdel-Jawad, H. (1981). Lexical and phonological variation in spoken Arabic in Amman. University of Pennsylvania.

Abdel-Jawad, H. (1987). Cross-dialectal variation in Arabic: Competing prestigious forms. Language in Society, 16(3), 359–367.

Abu Ain, N. (2016). A sociolinguistic study in SaHm, Northern Jordan (Issue June) [University of Essex]. http://repository.essex.ac.uk/19387/1/POSTVIVA4.pdf

Al-Ghamdi, N. (2019). The effect of age on dialect change: The case of diphthongs in a Saudi dialect. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, 18(1), 209–214.

Al-Hawamdeh, A. (2016). A sociolinguistic investigation of two Hōrāni features in Sūf, Jordan. University of Essex.

Al-Khatib, M. (1988). Sociolinguistic change in an expanding urban context: A study of Irbid city, Jordan [University of Durham]. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1696/1/1696.pdf?EThOS (BL)

Al-Wer, E. (2007). The formation of the dialect of Amman: From chaos to order. In C. Miller, E. Al-Wer, D. Caubet, & J. C. E. Watson (Eds.), Arabic in the City: Issues in dialect contact and language variation (1st ed., pp. 55–76). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Al-Wer, E., & Herin, B. (2011). The lifecycle of Qaf in Jordan. Langage et Societe, 138(4), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.3917/ls.138.0059

Al-Wer, E., Horesh, U., Herin, B., & De Jong, R. (2022). Arabic sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315722450-1

Balanche, F. (2015). “Go to Damascus my son”: Alawi demographic shifts under Baʿath Party rule. In M. Kerr & C. Larkin (Eds.), The Alawis of Syria: war, faith, and politics in the Levant (pp. 79–106). Oxford University Press.

Balanche, F. (2018). Sectarianism in Syria’s civil war: A geopolitical study featuring 70 original maps. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/media/4137

Bassiouney, R. (2017a). A new direction for Arabic sociolinguistics. In Perspectives on Arabic linguistics XXIX. Papers from the annual symposium on Arabic linguistics, Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Vol. 5, pp. 07–29).

Bassiouney, R. (2017b). Religion and identity in modern Egypt public discourse. In A. Gebril (Ed.), Applied Linguistics in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 37–60). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/aals.15.03bas

Bassiouney, R. (2018). Constructing the stereotype: Indexes and performance of a stigmatised local dialect in Egypt. Multilingua, 37(3), 225–253. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2016-0083

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 585–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407

Cheshire, J., & Gardner-Chloros, P. (1998). Code-switching and the sociolinguistic gender pattern. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 129(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1998.129.5

Chevrot, J. P., Beaud, L., & Varga, R. (2000). Developmental data on a French sociolinguistic variable: Post-consonantal word-final /R/. Language Variation and Change, 12(3), 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095439450012304X

Coates, J. (2003). Stories in the making of masculinities (1st ed.). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Cotter, W. (2016). (q) as a sociolinguistic variable in the Arabic of Gaza City. In Y. A. Haddad & E. Potsdam (Eds.), Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics XXVIII (pp. 229–246). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Daher, J. (1998). Gender in linguistic variation: The variable (q) in Damascus Arabic. In E. Benmamoun, M. Eid, & N. Haeri (Eds.), Perspectives on Arabic linguistics XI (Vol. 167, pp. 183–206). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Dendane, Z. (2013). The stigmatisation of the glottal stop in Tlemcen speech community: An indicator of dialect shift. International Journal of Linguistics and Literature (IJLL), 2(3), 1–10.

Eckert, P. (2005). Variation, convention, and social meaning. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Oakland CA. Jan. 7, 2005., 1–33. http://www.justinecassell.com/discourse09/readings/EckertLSA2005.pdf

Habib, R. (2005). The role of social factors, lexical borrowings, and speech accommodation in the variation of [q] and [ʔ] in the colloquial Arabic of rural migrant families in Hims, Syria (Issue August) [University of Florida]. http://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/UF/E0/01/17/20/00001/habib_r.pdf

Habib, R. (20100). Word frequency and the acquisition of the Arabic urban prestigious Form [ʔ]. Glossa, 5(2), 198–219.

Habib, R. (2010). Rural migration and language variation in Hims, Syria. SKY Journal of Linguistics, 23, 61–99.

Habib, R. (2011). Meaningful variation and bidirectional change in rural child and adolescent language. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Selected Papers from NWAV 39, 17(1), 81–90. http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol17/iss2/10/

Habib, R. (2016). Identity, ideology, and attitude in Syrian rural child and adolescent speech. Linguistic Variation, 16(1), 34–67. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.16.1.03hab

Habib, R. (2017). Parents and their children’s variable language: Is it acquisition or more? Journal of Child Language, 44(3), 628–649. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000916000155

Hachimi, A. (2007). Becoming Casablancan: Fessi in Casablanca as a case study. In C. Miller, E. Al-Wer, D. Caubet, & J. C. E. Watson (Eds.), Arabic in the city: Issues in dialect contact and language variation (pp. 97–122). Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

Hachimi, A. (2012). The urban and the urbane: Identities, language ideologies, and Arabic dialects in Morocco. Language in Society, 41(3), 321–341.

Haeri, N. (1997). The reproduction of symbolic capital: Language, state, and class in Egypt. Current Anthropology, 38(5), 795–816.

Khaddour, K. (2015). A “government city” amid ranging conflict (Tartous 2013). In F. Stolleis (Ed.), Playing the sectarian card: identities and affiliations of local communities in Syria (pp. 27–38). Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Labov, W. (1966). The effect of social mobility on linguistic behavior. Sociological Inquiry, 36(2), 186–203. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1966.tb00624.x/full

Labov, W. (1994). Principles of linguistic change. Volume I: Internal factors. Blackwell.

Llamas, C. (2007). “A place between places”: Language and identities in a border town. Language in Society, 36(4), 579–604. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404507070455

Mohamad, T. (2022). Investigating age as a social variable among Muslim Alawites in Tartus Syria: The Qaf as an example. Language in India, 22(June), 147–155.

Mohamad, T. (2023). The status of religion/sect-based linguistic variation in Tartus, Syria: Looking at the nuances of Qaf as an example. Languages.

Smith, J., & Durham, M. (2019). Sociolinguistic Variation in Children’s Language. In S. Tagliamonte (Ed.), Sociolinguistic Variation in Children’s Language. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316779248

Speelman, D. (2014). Logistic regression: A confirmatory technique for comparisons in corpus linguistics. In D. Glynn & J. Robinson (Eds.), Corpus Methods for Semantics: Quantitative studies in polysemy and synonymy (Vol. 43, pp. 487–533). John Benjamins.

Suleiman, Y. (2004). A war of words: Language and conflict in the Middle East (book) (1st ed). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819926

Tagliamonte, S. (2016). Making waves: The story of variationist sociolinguistics. Wiley Blackwell.

Trudgill, P. (1974). The social differentiation of English in Norwich. Cambridge University Press.

Wolfram, W., & Schilling, N. (2016). American English: Dialects and variation (3rd ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

[1] The (q) or Qaf in this text refer to the variable under study. The variants can be called [q] and [ʔ], or [qaf] and [ʔaf], respectively.