4 Japanese interactional particles: designing contents for teaching.

Giordano Stocchi

University of Naples ‘L’Orientale’, Department of Asian, African and Mediterranean Studies, Naples, Italy

gstocchi@unior.it

This paper seeks to provide a theoretical and methodological framework aiming at designing class content that enhances the Interactional Competence (Hall, 1999) of learners studying Japanese as a Foreign Language (JFL). It is worth noting that the present study is still in progress, and as such, the given account does not present complete data, analysis, or findings. The main objective of the research is to develop teaching materials using a corpus of spontaneous talk, the CEJC corpus (Corpus of Everyday Japanese Conversations) (Koiso et al., 2022), combined with Translanguaging (García & Wei, 2014) activities on the sentence-final particles ne, yo, and yone, important aspects of Japanese pragmatics. Teaching pragmatics is an innovative goal, and it involves a shift away from traditional grammar and vocabulary-focused approaches, developing learners’ communicative competence using interactive and experimental teaching methods that make language learning more engaging and effective.

Keywords: Japanese Language Teaching, Interactional Competence, Sentence-Final Particles, Translanguaging, Corpus of Spontaneous Talk.

- State of the art

During the past centuries, Japan has been a rather closed country, as contacts with the outside world were few and selected. However, the number of people studying Japanese and wishing to live in the country has grown exponentially in recent years. Consequently, intercultural situations between non-native speakers (NNS) and native speakers (NS) have become ordinary. Yet, the pragmatic focus in teaching the language is not common, and the communicative sphere is often undervalued.

The Japanese language presents some features that are deeply rooted in the society in which it originated. Plus, it belongs to the isolated Japonic family which is not related to other neighboring languages, such as Chinese or Korean. For this reason, a foreigner could find it difficult to acquire some specific linguistic structures that are inborn with being native, such as the particles, ne, yo, and yone; broadly known as shūjoshi[1] (sentence-final particles) because of their position at the end of the sentence.

2.1 Sentence-final particles: ne, yo, and yone

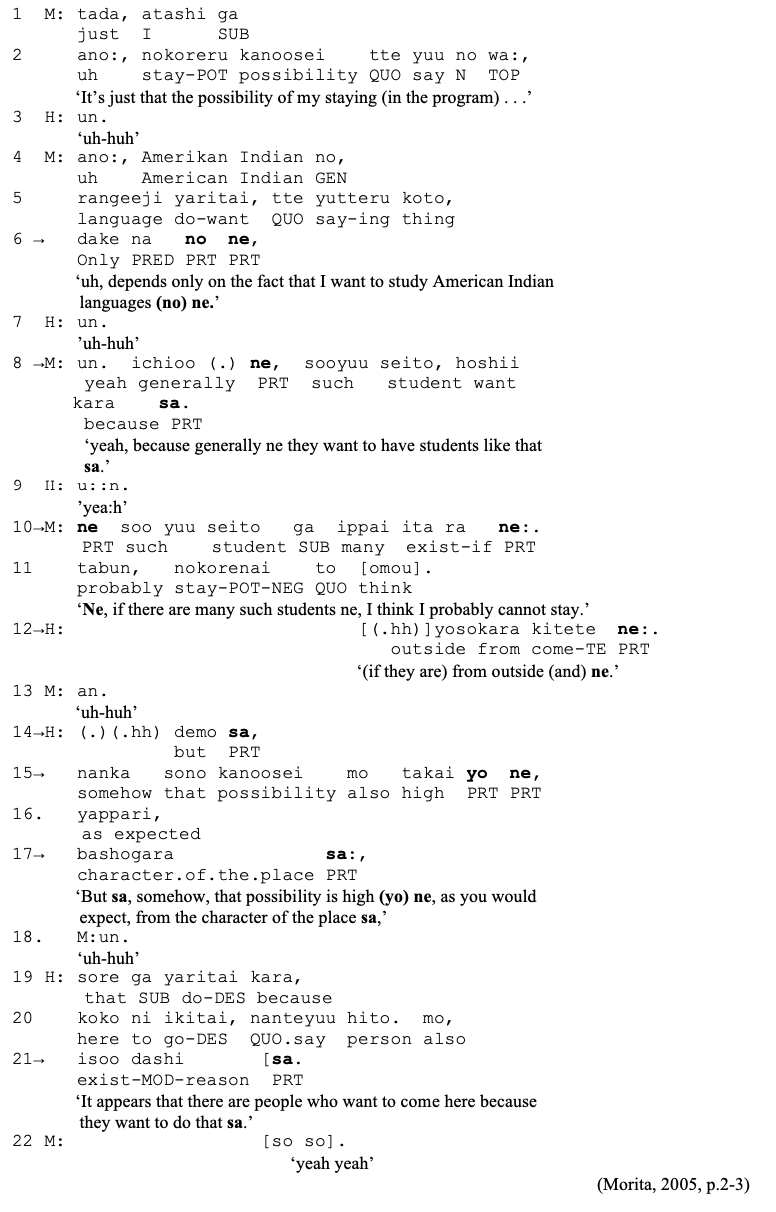

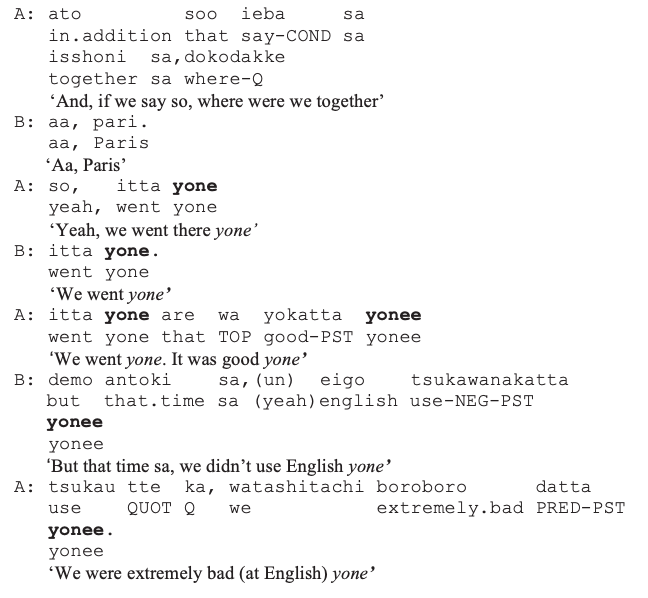

Ne, yo, and yone are among the most used particles in natural occurring interaction. As we can see in (cf. 1), in just fifteen seconds of conversation between two Japanese in an informal context, sentence-final particles appear predominantly (Morita, 2005).

(1)[2]

One can find diastratic and diatopic variations of ne, yo, and yone: they change according to the geographic area and the different social groups in which they are used. They appear to be used conspicuously in informal talk, instead, they are limitedly utilized in formal and written language. Not all of the particles are strictly used at the end of the sentence; they can appear also between various parts of the discourse, in this case, these are called kantōjoshi (insertion particles). For this study, we analyze them when they occur in the final position, since ne, yo, and their combination yone are the most frequently used in that way. Ne is also used frequently as an insertion particle, but when it comes to yo and yone the use as an insertion particle is limited to the stylistic choices of the speaker. Maynard (1993a, 1993b), considering 3-minute segments of 20 casual conversations between NSs, states that the particles ne and yo occur in with a ratio of 3:1 (1 yo every 3 ne), finding 364 ne, and 128 yo in the considered data in both insertion and sentence-final positions. In recognition of their importance in interaction, the particles ne, yo, and yone were renamed as Interactional Particles (IPs) by Maynard (1993a) and later by Morita (2005).

Despite their significant presence in speech, IPs have proven elusive in terms of functions and meanings in interaction. Moreover, ne, yo, and yone do not affect the utterances’ meaning, one can decide not to use them and there would not be any problem in communicating the message. However, it would change the way the message is performed and how the speaker relates to it and to the hearer, possibly making the statement odd. As a result, many scholars have investigated ne, yo, and yone from different perspectives in order to describe their usage and meanings.

IPs’ meaning can be mainly described by analyzing the amount of information shared by the speaker and the listener. The informational gap between the two corresponds to a certain use of ne, yo, and yone (Kamio, 1994; Maynard, 1993a; Ohso, 2005). Hereafter are some examples taken from Ohso’s work.

Ohso (2005), using the Nagoya University Conversation Corpus, tried to rethink the communicative functions of IPs. Ohso observed the data and tried to categorize standard cases in which the interactional particles are used by Japanese native speakers as it follows.

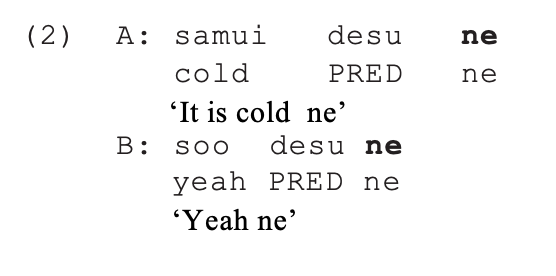

Ne is defined as a particle showing firstly when the information is shared between the two speakers. For instance, ne is used when talking about the weather (cf. 2).

(Annotated[3] and translated from Ohso 2005: 3)

The weather can be usually considered as something shared since face-to-face communication happens under the same condition.

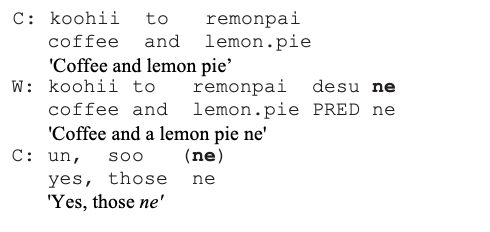

Ne is used also as confirmation seeking. Ohso brings the example (cf. 3) of a dialogue between a waitress (W) and a customer (C) where ne is needed.

(3)

(Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 3)

The usage of ne, in this case, allows the speaker to receive consent about the owned information and confirm its correctness.

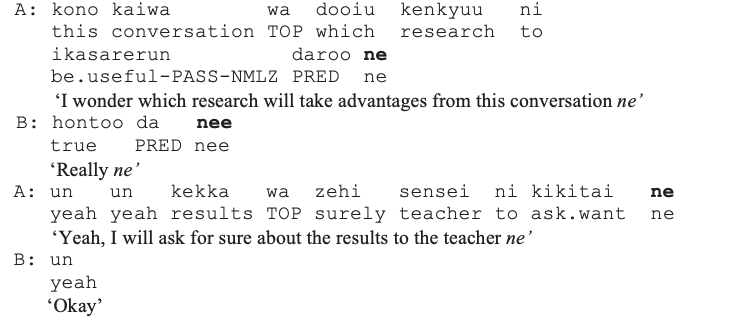

Another usage (cf. 4) is strictly linked to a friendly conversational practice; it is used to assume that the wish or the doubt of the speaker is shared with his hearer.

(4)

(Data 65, Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 4)

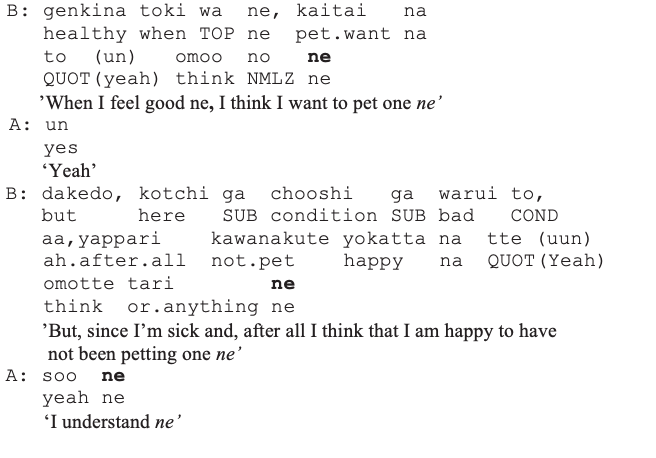

The last function of ne listed is the one that works as verification, to understand if what the speaker is saying has been followed by the listener. Usually, it is followed by an aizuchi[4] uttered by the hearer in response. As we can see in the following conversation (cf. 5), in which there are two persons talking about having a pet in the apartment.

(5)

(Data 31; Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 5)

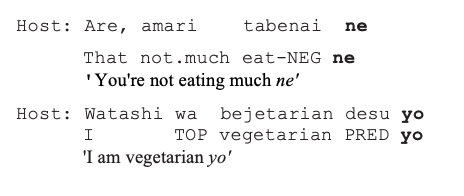

The particle yo, instead, is used when it is necessary to show clearly to the hearer the information (opinion, judgment, will etc.) in possession of the speaker. There are two cases in which we can find yo.

Firstly, when the hearer says something without having any valuable information about it, or when the speaker just wants to strongly refer to the knowledge that the hearer does not possess. Here is an example (cf. 6) taken from Ohso, in which the two speakers are talking about Belgium and the experience of living there.

(6)

(Data 65, Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 6)

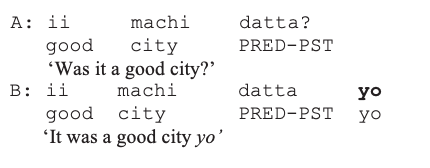

Secondly, when the speaker notices that the owned opinion differs from the hearer’s, and the speaker thinks it is important to show them with clarity the position, as we can see in the following example (cf. 7).

(7)

(Data 65, Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 7)

Yone, instead, is the combination of the previous two particles and owns their functions combined. Three are the principal uses according to Ohso (2005).

The first one is when the speaker previously acquired information, it shows that one already has the knowledge and asks for confirmation from the hearer. As we can see in the next example (cf. 8), the speaker looks for the confirmation of the already-known information.

(8)

(Data 53, Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 8)

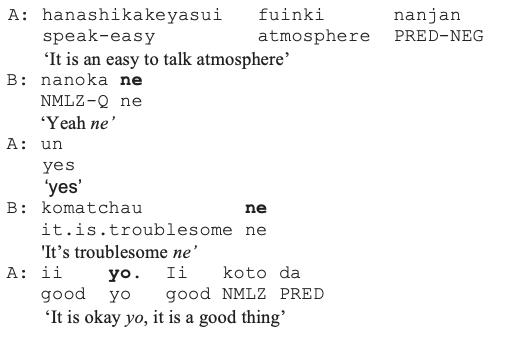

Secondly, when the speaker imagines that the hearer possesses the same information (cf. 9).

(9)

(Data 65, Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 9)

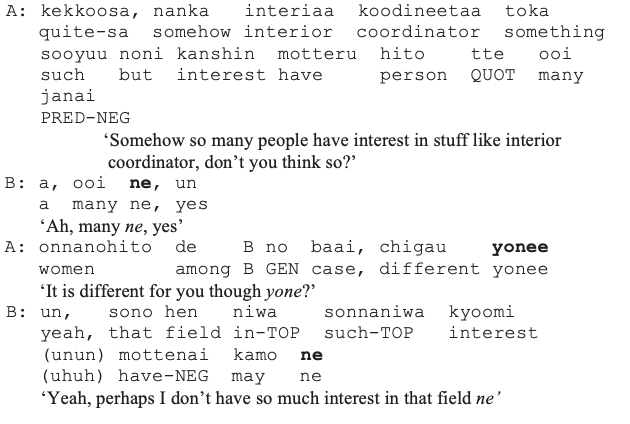

Last, yone is also used when the speaker imagines that the hearer would have the same opinion about the given information, even if he does not explicitly know it yet. It has the same meaning as a simple yo but adding ne shows the speaker’s pursuit of mutual understanding and consent, maintaining a friendly atmosphere between the two (cf. 10).

(10)

(Data 53, Annotated and translated from Ohso 2005: 10)

Alternative theories account for Interactional Particles as tools able to manage: the conversational involvement (Lee D., 2007), the affective common ground among interlocutors (Cook, 1992), and the harmony of the entire interaction seen as the main goal of Japanese conversations (Onodera, 2004).

Stating their importance in spoken utterances, Katagiri (2007) explains the particles in new terms. These can express the state of acceptance of the speaker on the information to the hearer, and accordingly, the hearer will decide if the information is acceptable or not. The scholar strongly believes that IPs are persuasion strategies, which is why they highly influence discourse in everyday interactions.

Starting from Morita (2005) and Saigo (2011), IPs are considered entities more closely related to dialogue. Their research, based on a Conversation Analysis[5] (CA) approach, sees the considered particles as resources for the co-construction of the current talk, having strong power in influencing the turn-taking structure and the position of all the speakers involved in the conversation.

One of the aims of the in-development project is to rethink the particles’ functions taking into account the informational value (Kamio, 1994; Maynard, 1993a; Ohso, 2005), bridging it to the conversational nuances (Morita, 2005; Saigo, 2011). The revised descriptions will be elicited through the analysis of the corpus of spontaneous talk (CEJC) (cf. paragraph 3.2), the main source for the whole project.

1.1 Acquisition

Japanese children can use IPs in different facets from a very young age (Clancy, 1985). Ne and yo, are the two showing earliest, appearing in children’s utterances between 1,6-2 years.

[…] it seems likely that at least some children can use sentence-final particles productively while the majority of their utterances still consist of a single word. It is particularly striking that these particles, which are extremely difficult for foreigners to master and use naturally, are acquired so early by Japanese children. (Clancy, 1985: 428)

This can be explained by considering the particles’ pragmatic functions and emotional basis which make the children want to use them to connect with adults. The particles also appear to be a strong presence in babytalk[6]: notably, caregivers finish most of their sentences directed to children using ne or yo. This frequent amount of inputs enables Japanese children to acquire IPs at an early age, while, on the contrary, they can be a tough topic for learners of Japanese as a second language.

Japanese language learners struggle with the acquisition of sentence-final particles, even when introduced to IPs early on. In this section, we explore research on the use of ne, yo, and yone by learners. Plenty of qualitative studies show that learners tend to use IPs inaccurately resulting in discomfort for native speakers. Differences in the functions used can be observed, based on the learners’ proficiency level.

Hajikano’s (1994) study analyzed the usage of sentence-final particles, focusing on the particle ne, among four beginner Japanese learners over the course of a year. The research showed that ne was the easiest particle to appear. The study identified individual differences in acquisition processes among the learners, with one subject showing gradual improvement in using ne correctly. However, the results cannot be generalized due to the small sample size. According to Hajikano learners tend to use ne incorrectly at an early stage and use other particles, such as yo and yone, less frequently.

Intermediate-level Japanese learners tend to overuse interactional particles, which native speakers may perceive as rude, according to Kō (2008) and Koike (2000). In Koike’s study, roleplays between native-speaker of Japanese teachers and intermediate-to-upper-intermediate level non-native students have been recorded. Six university evaluators noted that the non-native speakers used the sentence-final particles ne and yo excessively. One of the evaluators commented that using about half as many would have been better, as excessive use can be considered inappropriate.

The uses in advanced speakers come closer to the native’s ones: mostly every particle appears to be used, but not always correctly (Lee S., 2001). The study by Lee S. (2001) compared the use of ne, yo, and yone between Japanese native speakers and Korean learners with an advanced level of Japanese. The research involved ten Japanese native speakers who were master’s students in their twenties and thirties, and ten Korean learners who had studied Japanese for more than five years, with only one student having studied for less than three years. During the study, participants engaged in roleplay conversations guided by general topics such as marriage, job hunting, and living abroad. Overall, the research suggests that after living in Japan for an extended period and having studied the Japanese language for long, advanced learners of Japanese can generally use ne, yo, and yone but still showing some room for improvement.

Previous research shows how the IPs’ acquisition is a really long process in which strong is the influence of one’s individual characteristics and personal experience of living the language in Japan.

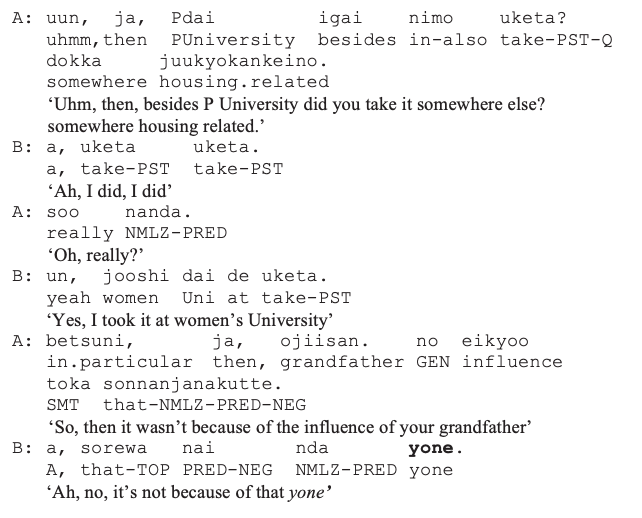

The uses of IPs by learners of Japanese disclose problematic situations in intercultural communication. Misusing or not using ne, yo, and yone when needed can result in uncomfortable feelings on the side of native speakers (Koike, 2000). Nazikian (2005) gives an example (cf. 11) of a possible situation in which the use of the wrong particle could lead to communicative problems in an intercultural communication setting. She presents a situation in which a home-staying student in Japan is talking with their hosts.

(11)

(Annotated, adapted, and translated from Nazikian, 2005: 168)

Responding to a kindly uttered invite to feel free to eat more using yo makes the statement strong, stressing one’s position on something that the hearer must be aware of (in this case the fact that the student is vegetarian), consequently, possibly creating negative feelings on the Japanese speaker’s side. This example highlights the significance of Interactional Particles in Japanese communication. Acquiring these particles is crucial for expressing respect, building rapport, and ensuring smooth interactions. Without a solid understanding of these particles, NNSs may struggle to navigate social interactions and effectively communicate their intentions and emotions.

As noted by Clancy (1985), however, it is impossible to replicate the ideal environment and input conditions necessary for Interactional Particles acquisition in a classroom setting.

Perhaps these particles are so difficult for Westerners learning Japanese as a second language because their usage is so context-dependent that ordinary classroom instruction cannot duplicate the appropriate conditions for acquisition. (Clancy, 1985: 435)

Looking for more reasons concerning the failure encountered in acquiring IPs by NNSs, it can be stated that comments in Japanese language textbooks are scarce, and often do not effectively display their pragmatic functions (Hoshi, 2017; Kō, 2011). Furthermore, IPs when misused are usually not corrected in class (Nazikian, 2005), since the message conveyed in the utterance is not damaged. This inconsistency in teaching important communicative resources such as IPs stresses the lack of importance of the communicative sphere in Japanese language education.

Different studies have shown that the acquisition of the IPs, can be facilitated by experiencing native input in the Japanese context (Masuda, 2011). However, one more recent research (Kizu et al., 2019) has shown how often not even an abundance of inputs in the native context is a decisive factor for the acquisition of these structures. It can be argued that the acquisition process is closely linked to the subjectivity of the learner. However, developing teaching materials with detailed explanations and exercises on Interactional Particles can enhance learners’ sensitivity to the topic, thereby facilitating the successful acquisition of their uses. A more suitable way of teaching ne, yo, and yone needs to be implemented (Kizu et al., 2013) and more attention has to be given to the oral and written production of the Japanese language (Hatasa & Watanabe, 2017).

Little has been researched on how instructions in class can influence JFL learners’ acquisition of ne, yo, and yone. Kakegawa (2009) accounted for instructional effects on the development of students’ uses of the particles, implementing activities on ne, yo, no, and yone through email correspondence with NSs. Moreover, Hoshi (2017) developed well-organized lessons on Interactional Particles’ pragmatic uses, demonstrating how instructions benefit the acquisition of Japanese IPs when opportunities for communication with NSs are presented as a component of the learning process. She also suggests that diverse instructional approaches need to be studied and implemented. Hoshi (2017) states that introducing authentic discourse data in class could help develop students’ pragmatic knowledge. Although, this is a procedure hardly applicable when students’ proficiency level is not high enough.

- Project

Given the existence of the gap in the literature concerning the teaching and acquisition of the IPs in NNSs, the current project aims to develop class contents using the CEJC (Corpus of Everyday Japanese Conversation) (Koiso et al., 2022) (cf. paragraph 3.1) combined with Translanguaging (cf. paragraph 3.2) activities in class.

2.1 CEJC – Corpus of Everyday Japanese Conversations

The role the particles assume can be stressed using the CEJC corpus (Corpus of Everyday Japanese Conversations) (Koiso et al., 2022) to elaborate activities to teach the sociocultural norms of Japanese interaction. Developed by NINJAL (National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics), the CEJC corpus comprises 200 hours of spontaneous conversations in various formal and informal settings for a total of 1675 conversants, including 862 different participants. It is available in audio, video, and transcript formats, upon request from the institution. The data were manually transcribed and linked to the video through ELAN[7] (ELAN, 2022) and/or Praat[8] (Boersma & Weenink, 2023). The programs were used to give more precise annotations of talk.

Corpus of naturally occurring conversations has been widely recognized as beneficial to the Foreign Language Teaching field of study (Römer, 2011).This is planned through a CA-informed approach: naturally occurring speech facilitates the discovery of previously unknown regularities of human interaction (Sacks et al., 1974). The CEJC corpus is supposed to be used directly, as Bernardini (2002) suggests: learners will be linguistic researchers involved in the discovery of the class topics by analyzing the corpus itself. The use of a corpus as the basis of language lessons exposes learners to spontaneous talk input, facilitating the understanding of interactional resources in the contexts of use (Barraja-Rohan, 2011).

2.2 Translanguaging

Translanguaging is planned to be employed as a facilitator of activities involving the corpus. The concept was born as a pedagogical resource used in the multilingual classroom, allowing the students to use their linguistic skills and experiences acquired in their L1 as well as other languages, to develop new knowledge in a new language. As argued by García & Wei (2014) these practices are naturally occurring when an emergent bilingual is learning a new language. Translanguaging is based on the recognition that individuals possess multiple linguistic abilities that coexist within a bilingual continuum. It acknowledges that languages can influence each other as their boundaries become blurred. This practice not only allows the students to build new knowledge more easily but also helps them to strengthen the weaker language of their repertoire (Baker, 2001).

It is only recently that Translanguaging has started to be considered applicable to Foreign Language Teaching. Research on the potential benefits of the use of the L1 or other languages that the students already mastered in-class activities is gaining momentum in the academic discourse. The idea of replacing common practices (Target language focused) with Translanguaging practices is also being considered particularly valid. Translanguaging teaching technique provides multiple benefits: students learn new concepts with ease through it, being able to adapt to it effortlessly. It also allows the creation of a relaxed learning atmosphere that could be beneficial to weaker students, making them gain the confidence they need to actively participate in the activities (Chukly-Bonato, 2016; Nagy, 2018)

2.3 Research questions

The starting assumption is that Translanguaging could help suppress the emergence of the so-called affective filter[9] (Krashen, 1988). Moreover, since the particles ne, yo, and yone are invested with high social value, the combination of Translanguaging tools with the use of a corpus could ease the exchange of impressions, deriving both from the fruition of examples selected from the corpus and from any direct experiences previously encountered by students. Hence, the research questions set for the study are:

- What are IPs’ functions found, considering previously given definitions, through the analysis of the corpus of spontaneous talk?

- How can a teaching unit be structured on the Interactional Particles using the corpus of spontaneous talk and Translanguaging techniques?

- What are the benefits of using the corpus of spontaneous talk and Translanguaging when aiming to improve JFL learners’ Interactional Competence?

- What are the stances of students towards the use of the corpus and Translanguaging in class?

2.4 Research design

The particles’ definitions and uses will be reconsidered through the analysis of the CEJC corpus. The study will analyze the functions considering the state of the art on the topic, but always referring to the spontaneous uses occurring in the corpus itself.

From the analysis, representative extracts of videos linked to the functions elicited will be used to structure the teaching unit. The lessons including the spontaneous corpus will be developed and presented to a trial group of students. The upcoming is a possible class structure, outlined following the steps described by CEFR[10] (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) to build a teaching module developed in different phases, combined with Translanguaging activities that will allow the mutual switch from L1 to the target language from phase to phase:

- pre-introductory – evaluation of the students’ pragmatic use of the particles

- introductory – motivational phase, explaining the strong value of the particles in conversation and asking the students to share experiences and opinions on the particles,

- initial – show the selected extracts of CEJC, then distribute transcriptions of the shown passages,

- central – divide the students into groups, with the task of analyzing the uses and reporting orally to the class what was discovered, using then their production to explain and discuss the actual uses of the particles,

- final – elaborate roleplays or activities that make the students use the particles to better understand and acquire them,

- conclusive – evaluation of the lesson’s results and feedback from the students.

Participating students will be gathered from Japanese classes (master’s degree level) of the University of Naples ‘L’Orientale’, considering their level of proficiency in Japanese between intermediate-to-advanced. The non-participating students, attending the ordinary curricular Japanese classes, will be employed as the control group as proof of the validity of the research. Students who have an elementary level of proficiency will be excluded from the study because they may not be able to comprehend some of the cultural subtleties associated with the uses of IPs. Furthermore, they may find the corpus of spontaneous conversations too complex even with the implementation of Translanguaging in class.

Aiming at evaluating the benefits of the planned methodology, the study will assess the students’ output in a pre-introductory and a final phase to evaluate if their ability in the use of ne, yo, and yone improved through the lessons. It will also evaluate students from the control group, with the same assessment tasks on the IPs. This will be done to prove that students participating in the research are able to better grasp the meanings and functions of ne, yo, and yone.

In order to investigate the stances of students towards the use of the corpus and Translanguaging in class, in the conclusive phase, they will be asked to fill out a written survey. Based on the answers given, follow-up interviews will be conducted with some of the students whose answers may result to be particularly relevant to the purpose of the research. To this end, the questionnaire will help with the understanding of the students’ feelings toward the teaching methodology. It will also help in collecting the opinions and feedback needed to appropriately evaluate the impact of the teaching method on their personal learning experience.

2.5 Relevance

The present research aims to develop the students’ ability to better understand Japanese conversation practices, making them transculturally competent and able to distinguish the right strategy for the cultural context where the conversation is situated, especially when it comes to Japanese Interactional Particles’ uses.

The objective is to give new importance to pragmatics in talk-in-interaction in Japanese pedagogy, developing new strategies based on recent findings in Foreign Language Teaching. Teaching pragmatics is of utmost importance as it helps learners to effectively communicate and comprehend meaning beyond the literal level. Pragmatic knowledge is essential for learners who wish to interact effectively in real-life situations, especially when communicating with native speakers of the target language. When learners have a good grasp of the pragmatics of a language, they are more likely to be successful in achieving their communicative goals, making a good impression, and building rapport with native speakers. This is particularly important for individuals who intend to work or study in a foreign country, where the understanding and respect of the local culture is crucial for success.

In Japanese, the interactional particles ne, yo, and yone are of great importance to be pragmatically and interactionally competent. Therefore, improving teaching-related activities in the Japanese as a Foreign Language classroom becomes salient, making the ongoing project relevant to Japanese pedagogy.

References

Baker, C. (2001). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (3rd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Barraja-Rohan, A.-M. (2011). Using conversation analysis in the second language classroom to teach interactional competence. Language Teaching Research, 15(4), 479–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168811412878

Bernardini, S. (2002). Exploring New Directions for Discovery Learning. In Teaching and Learning by Doing Corpus Analysis (pp. 165–182). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004334236_015

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2023). Praat: doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.3.09). http://www.praat.org/

Chukly-Bonato, K. (2016). Transferring knowledge through translanguaging: The art of multilingualizing the foreign language classroom. McGill University .

Clancy, P. M. (1985). The acquisition of Japanese. In The cross-linguistic study of language acquisition: Vol. Volume 1 (pp. 373–524). Publishers Hillsdale.

Comrie, B., Haspelmath, M., & Bickel, B. (2008). The LeipziGlossing Rules: Conventions for Interlinear Morpheme-by-morphene . Https://Www.Eva.Mpg.de/Lingua/Resources/Glossing-Rules.Php.

Cook, H. M. (1992). Meanings of non-referential indexes: A case study of the Japanese sentence-final particle ne. Text – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 12(4), 507–540. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1992.12.4.507

ELAN (Version 6.4). (2022). Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archivehttps://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan. https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan

García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137385765

Hajikano, A. (1994). Shokyūnihongo gakushūsha no shūjoshi shūtoku ni kansuru ichikōsatsu – “ne” o chūshin to shite [A study of beginning Japanese learners’ acquisition of sentence-final particles – focusing on ne ]. Gengo Bunka to Nihongo Kyōiku [Language Culture and Japanese Language Education] , 8, 14–25.

Hatasa, Y., & Watanabe, T. (2017). Japanese as a Second Language Assessment in Japan: Current Issues and Future Directions. Language Assessment Quarterly, 14(3), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2017.1351565

Hoshi, S. (2017). “That movie was so hilarious ne!” The development of Japanese Interactional Particles ne, yo, and yone in L2 classroom instruction. University of Hawai’i.

Kakegawa, T. (2009). Development of the use of Japanese sentence-final particles through email correspondence. In N. Taguchi (Ed.), Pragmatic Competence (pp. 301–333). Mouton De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110218558.301

Kamio, A. (1994). The theory of territory of information: The case of Japanese. Journal of Pragmatics, 21(1), 67–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)90047-7

Katagiri, Y. (2007). Dialogue functions of Japanese sentence-final particles ‘Yo’ and ‘Ne.’ Journal of Pragmatics, 39(7), 1313–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.02.013

Kizu, M., Pizziconi, B., & Gyogi, E. (2019). Particle ne in the development of interactional positioning in L2 Japanese. East Asian Pragmatics, 4(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.1558/eap.38217

Kizu, M., Pizziconi, B., & Iwasaki, N. (2013). Modal Markers in Japanese: A Study of Learners’ Use before and after Study Abroad. Japanese Language and Literature, 47(1), 93–133.

Kō, M. (2008). Sesshokubamen ni okeru shūjoshi shūjoshi no gengokanri: Hibogowasha no shūjoshi “ne” to “yo” no shiyou o chūshin ni [The language management of the final particle in contact: focusing on the final particles ‘Ne’ and ‘Yo’ used by non-native speakers]. Jinbun Shakai Kagaku Kenkyūka Kenkyū Purojekuto Hōkoku-Sho [Humanities Graduate School of Social Sciences Research Project Report], 198, 97–112.

Kō, M. (2011). Nihongo gakushūsha no “yo” “ne” “yone” ni tsuite – nihongo shokyū chūkyū kyōkasho no kinō bunseki o chūshin ni [On Japanese learners’ “yo” “ne” “yone” – Focusing on functional analysis of Japanese elementary and intermediate textbooks] . Kokusai Kyōiku [International Education], 4.

Koike, M. (2000). Nihongo bogowasha ga shitsurei to kanjirunowa gakushūshano donna hatsuwa ka: (irai) no bamen ni okeru bogowasha no hatsuwa to hikou to shite [What learner’s utterances do Japanese native speakers find rude: comparison with the native speaker’s utterance in the request scene]. Hokkaidō Daigaku Ryūgakusei Sentā Kiyou [Journal of International Student Center], 4, 58–80.

Koiso, H., Amatani, H., Den, Y., Iseki, Y., Ishimoto, Y., Kashino, W., Kawabata, Y., Nishikawa, K., Tanaka, Y., Usuda, Y., & Watanabe, Y. (2022). Design and Evaluation of the Corpus of Everyday Japanese Conversation. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, 5587–5594. https://aclanthology.org/2022.lrec-1.599

Krashen, S. D. (1988). Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Prentice-Hall International.

Lee, D.-Y. (2007). Involvement and the Japanese interactive particles ne and yo. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(2), 363–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2006.06.004

Lee, S. (2001). Giron no ba ni mirareru `ne’ `yo’ `yo ne’ ni tsuite: Nihongo bogo washa to kangokujin gakushū-sha to no sōi [Discussion on “Ne” “Yo” and “Yone”: differences between native Japanese speakers and Korean learners] . Nagoya Daigaku: Kiyō Ronbun [Nagoya University: Departmental Bulletin Paper], 14, 41–71.

Masuda, K. (2011). Acquiring Interactional Competence in a Study Abroad Context: Japanese Language Learners’ Use of the Interactional Particle ne. The Modern Language Journal, 95(4), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01256.x

Maynard, S. K. (1993a). Discourse Modality: Subjectivity, Emotion, and Voice in the Japanese Language. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Maynard, S. K. (1993b). Kaiwa Bunseki [Conversation Analysis] (Kuroshio Shuppan).

Morita, E. (2005). Negotiation of Contingent Talk: The Japanese Interactional Particles Ne and Sa. John Benjamin Publishing Company.

Nagy, T. (2018). On Translanguaging and Its Role in Foreign Language Teaching. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica, 10(2), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.2478/ausp-2018-0012

Nazikian, F. (2005). Shūjoshi `yo’`ne’ to nihongo kyōiku [Sentence final particles “yo” “ne” and Japanese language education]. In Gengo kyōiku no shintenkai – Makino Seiichi – kyōjun Kōki kinen ronshū [New developments on language teaching – Professor Kōki Memorial Collection] (pp. 167–180).

Ohso, M. (2005). Shūjoshi yo, ne, yone, saikō – zatudan kōpasu ni motoduku kōsai – [Reconsideration of final particles “yo” “ne” “yone” – Consideration based on a talk corpus]. In Gengo kyōiku no shintenkai – Makino Seiichi – kyōjun Kōki kinen ronshū [New developments on language teaching – Professor Kōki Memorial Collection] (pp. 3–15). Hituji shobō.

Onodera, N. O. (2004). Japanese Discourse Markers. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.132

Römer, U. (2011). Corpus Research Applications in Second Language Teaching. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190511000055

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language, 50(4), 696. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

Saigo, H. (2011). The Japanese Sentence-Final Particles in Talk-in-Interaction (Vol. 205). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.205

[1] When transcribing Japanese language in the Roman alphabet the Hepburn system is adopted.

[2] In the transcription the Courier New font is used since it allows to better display the glossa and the characteristics of talk. The following is the glossa used in Morita (2005): DES-Desiderative; MOD-Modal auxiliary; N-Nominalizer; POT-Potential form; PRT-Interactional particle; QUO-Quotative; SUB-Subject; TE-Conjunctive form.

[3] In the examples annotated by the author the Leipzig Glossing system is adopted (Comrie et al., 2008)

[4] Aizuchi (backchannels) are the interjections frequently used during a conversation to show to the speaker we are listening to what is said and that we are involved in talk.

[5] Approach used to study social interaction investigating the ongoing talk through the analysis of multimodal stances. The aim is to describe patterns of talk and the rules permeating social interactions.

[6] Babytalk or motherese, is a simplified version of language adopted by adults to interact with children. This consists of simpler grammar, long pauses, and limited vocabulary. The terms used can be modified, or new playful terms can be coined.

[7] ELAN allows the researcher to manually take notes on videos, making it possible to clearly outline overlaps, pauses, and different notes on the occurring utterances.

[8] Praat is a software used in the analysis of speech in phonetics.

[9] Self-defense mechanism that acts negatively, hindering learning, when the task or the object of the class is too complex for students.

[10] https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/level-descriptions